JAPANESE PRINTS

A MILLION QUESTIONS

TWO MILLION MYSTERIES

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

| Port Townsend, Washington |

|

UTAGAWA KUNISADA II 二代歌川国貞 うたがわくにさだ |

|

Subject: Jigoku Dayu 地獄太夫 じごくだゆう |

|

Actor: Band˘ Hikosabur˘ V 五世坂東彦三郎 ばんどひこさぶろう |

|

Date: 1865, 3rd Month |

|

Bunkyű 4 文久4 |

|

Publisher: Iseya Kanekichi 版元: 伊勢屋兼吉 はんもと: いせやかねきち |

|

Size: 13 3/4" x 9 1/4" |

|

SOLD! THANKS! |

|

|

|

JIGOKU DAYU THE HELL COURTESAN 地獄太夫 じごくだゆう |

|

There is a story about the fifteenth century Zen monk Ikkyū (一休 or いっきゅう) who wandered about posing puzzling questions to anyone who would listen. The questions which probably were completely unanswerable were meant to edify and to lead eventually to Buddhist enlightenment. Nearly two hundred years after Ikkyū died an apocryphal tale claimined that the monk had encountered a famous courtesan who referred to herself as Jigoku Dayu. The two traded poems. In time the legend was expanded and took on a life of its own. By the nineteenth century it held a particular fascination.

In 1809 Santō Kyōden (山東京伝 or さんとうきょうでん) published Honchō sui bodai zenden which dealt with this encounter between what ordinarily would be viewed as the sacred and profane. Kyōden's work inspired a number of later fine artists including Kuniyoshi, Kunisada II, Kunichika and Yoshitoshi. (1) It is not surprising that Kyōden would treat such a subject because that was the genre which dominated his works. (2) Mokuami (黙阿弥 or もくあみ), who was one of the most prolific and popular playwrights of the mid-nineteenth century, wrote Jigoku Ikkyū-banashi which debuted on New Year's 1865. (3) |

|

***** |

|

"Let me tell you something, let me tell you something. A lot of those that you see in the stories is not true, but at the same time, I have to tell you that I always say, that wherever there is smoke, there is fire. That is true."

Quote from Arnold Schwarzenegger (アノルド シュワルツェネッガ) while running for governor on October 2, 2003.

Ikkyū (1394-1481) actually lived, but I can't be so sure about that particular courtesan. However, the stories that developed around his encounters with Jigoku Dayu make a lot of sense historically.

Ikkyū claimed to be the son of an emperor of Japan. This may or may not be true. What we do know is that he was never an imperial prince. Donald Keene acknowledges this, but adds: "...there is evidence in Ikkyū's poetry that he believed himself to be of imperial stock, and he often visited the palace to see the emperor." (4)

At the age of five his mother sent him to a temple to study to be a priest. Over the years he became well known for his keen mind, devotion and piety. Various stories are told of his unconventional nature and how that won him fame. Like Siddhartha in Hermann Hesse's novel Ikkyū spent years of religious adherence and abstinence only to give that up for the pleasures of the flesh. Not only did he seek out women, but boys too. (5) One of his more famous poems, The Brothel, describes the embraces of an elderly Zen priest and a prostitute. His peers expressed shock and abhorrence at his behavior., but he countered by charging them with hypocrisy. His counterclaim is more believable. (6) |

|

1. Demon of Painting: The Art of Kawanabe Kyōsai, by Timothy Clark, British Museum Press, 1993, p. 100. 2. In World Within Walls: Japanese Literature of the Pre-Modern Era 1600-1867 by Donald Keene the author gives a thorough description of Kyōden's work. On page 407 Keene describes an early collection of short stories describing forty-eight different ways of procuring a courtesan. One sincere male guest describes his enormous financial debt because of his love for this one woman. When she blames herself he tells her that he would rather wear rags than be without her. Awwwwwwwwwwwwwwwww, ain't that sweet. 3. Clark, p. 101. 4. Some Japanese Portraits, by Donald Keene, Kodansha International Ltd., 1983, p. 19. 5. Ibid., p. 23. 6. Ibid., pp. 22-3. Ikkyū excoriated many of his peers, but saved the best for his description of Yōsō, the twenty-sixth abbot of the Daitoku-ji. Keene tells us that he referred to him as "...a poisonous snake, a seducer and a leper." Don't hold back Ikkyū. Tell us what you really think. He also parallels the railings of Martin Luther who criticized the papacy for its selling of indulgences. Important Zen religious figures extorted money out of patrons with the promise of salvation. |

| CROSSING OVER |

|

|

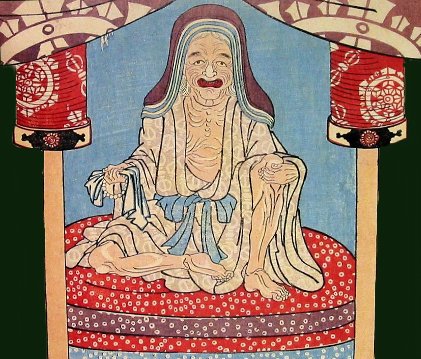

The Greeks believed that when a person died the boatman Charon would ferry the soul of the deceased across the river Acheron to Hades.(1) In Japan Charon's near counterpart was Datsue-ba (奪衣婆 or だつえば), the Old Hag of Hell, seen above. (2) While the Old Hag does not ferry the souls to Hell she does sit by the river which flows into it, i.e. Sanzu no kawa(三途の川 or さんずのかわ), and strips the damned of their robes which she hangs on a tree before their descent into the depths. |

|

|

|

(1)There was one proviso before Charon could transport a soul across the river. Upon death and proper burial or cremation a coin called an obol was placed under the tongue. When the soul reached the riverbank the coin acted as payment to the ferryman for the crossing. No coin, no transportation! --- at least not yet. Souls who failed to pay had to wander the shoreline for what some sources say was one hundred years before the crossing could be made.

Although I seriously doubt that there is any connection this is not totally dissimilar to ancient Chinese practice of placing a jade cicada in every orifice of a corpse. The Chinese believed that the cicada would die only to be reborn years later and these jade pieces would aid the soul of the deceased in their re-birth or resurrection in the afterworld. |

|

"O, be thou my Charon, And give me swift transportance to those fields Where I may wallow in the lily-beds.." Troilus to Pandarus, Act III, Scene II of "Troilus and Cressida" by William Shakespeare. |

|

Edna St. Vincent Millay, that ever upbeat

poetess, also wrote about Charon

in her "Sappho Crosses the Dark River into Hades." |

|

There are a number of versions of a famous painting by Arnold B÷cklin, a late nineteenth century Swiss artist. Most people know this painting by the title "The Isle of the Dead." It portrays a picture of an oarsman, presumably Charon, delivering a totally swathed, mysterious standing figure seen from the back to an equally mysterious island. I am not a B÷cklin scholar and have no idea what the artist intended, but what I do know is that the this is not B÷cklin's title for the painting, but rather one chosen for it by an art dealer sometime later. The name stuck. |

|

|

|

One other thought: when we are children we can ask one of our parents "What is that?" It could be about almost anything and unless the parent doesn't know the answer the child becomes just that much more informed. As we grow older, if we are still curious enough, we can look things up for ourselves --- that is, if the information is out there and is readily available. That is the major problem: so much remains unanswered. I do not know much about Datsue-ba, but would like to know more. If anyone can assist me it will be greatly appreciated. |

|

The information on Datsue-ba comes from a great catalogue, The Demon of Painting: The Art of Kawanabe Kyōsai by Timothy Clark, pages 87-9. People who are interested in Japanese culture do not have to be interested in Kyōsai to want to own this book. This book is a font of information. I recommend it highly. (2) While researching Datsue-ba I found that there were two alternate readings of the kanji for her name: 奪衣婆 or 脱衣婆. Furthermore, I ran across the fact that 脱衣 means "to undress" or "taking off of one's clothes" and that a "dressing room" or "bathhouse" is a 脱衣所. All of these are certainly appropriate relationships linguistically to role played by the Hag of Hell. |

|

Fresh information on Datsue-ba |

|

| Detail shown above of an enshrined image of Datsue-ba by Kuniyoshi. |

|

On July 31, 2004 we asked our Internet visitors if anyone out there could provide more information about Datsue-ba. That day A.K., a frequent correspondent and contributor to this site, wrote to tell us of a web page posted by the Institute of Medieval Japanese Studies at Columbia University which summarized recent research on this figure. The main points stated that 1) Datsue-ba is first mentioned in a spurious Chinese sutra which deals with Bodhisattva Jizo and the Ten Kings of Hell. Along with a elderly, demonic male companion she punishes a thief, ties his head to his feet, strips him of his clothes and send him off to his final judgement. 2) In a 13th century work she skins the sinner if they arrive without clothes. 3) The Old Hag may also function as a goddess: At birth she may provide the newborn with their skin which she will remove at their death. |

|

Datsue-ba and her connection with the Blood Pool Hell chi no ike jigoku 血の池地獄 |

|

|

|

According to some sources there was a special torment reserved for certain women called the Blood Pool Hell. It is closely related to a belief systems dealing with pregnancies - both successful and failed. Here Datsue-ba played a different role and evolved into "a guarantor of safe childbirth." At birth she provides each child with a "placental cloth" which must be returned at the time of death. |

| THE FINEST KABUKI SITE ON THE INTERNET! |

| http://www.kabuki21.com/index.htm |

|

For additional information about and images by various artists of link to the web site below. |

| BANDď HIKOSABURď V |

HOME

HOME