JAPANESE PRINTS

A MILLION QUESTIONS

TWO MILLION MYSTERIES

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

|

formerly Port Townsend, Washington now Kansas City, Missouri |

|

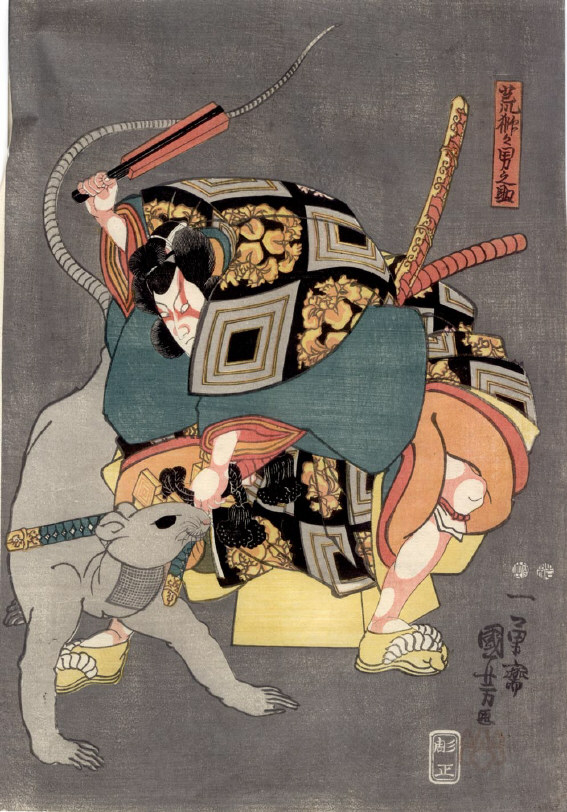

UTAGAWA TOYOKUNI III |

|

歌川豊国三代 |

|

1786-1865 |

|

Subject: Raigō Ajari (releasing the rats) 頼豪阿闍利 |

|

Actor on the right is Ichikawa Ichizō III 市川市蔵 |

|

Actor on the center panel is Ichikawa Kodanji IV 市川小團次 |

|

Actors on the left are to be identified later. The lower character is 三日月の三五郎. |

|

Date: 1861 Bunkyū 1 文久1 |

|

Signed: Toyokuni ga 署名: 豊国画 |

|

Publisher: Izutsu-ya Sanemon 版元: 井筒屋三右衛門 |

|

Carver: Horikō Masu (?) |

|

Print Sizes: 13 1/4" x 9 3/4" each |

|

There is another copy of this triptych in the Hankyu Culture Institute. |

|

SOLD! |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THEATER IS THEATER AND FACT IS FACT |

|

|

|

Imagine a scene where Benjamin Disraeli shows up to give advice to Maggie Thatcher or Newton is seen having a latte with Einstein at a chic coffeehouse. Time and place are incidental. In the theater everything is possible. That is one of the luxuries of the playwright and one that was used (abused?) aplenty in the kabuki theater. Anachronisms abound and no one seems to notice or if they do no one seems to care. Such is the case of the plays involving Raigō.

In Nue no Mori Ichiyō no Mato (Forest of the Nue Monster: Target the Eleventh Month) Raigō has fasted for one hundred days and looks the part. In this state he meets with Minamoto no Yorimasa who was born twenty years after the historical Raigō had died. But what the heck, this is the theater. "Kabuki playwrights...characteristically and enthusiastically conflated the most disparate events and stories, in order to thicken their plots or perhaps to provide a showcase role for a particular actor's talents." (1) Raigō and a follower go to the mansion of Yorimasa to plead for the construction of an ordination platform. "Yorimasa refuses the request, and somehow Raigō is made to drink poisoned sake. He dies in agony and is transformed into a horde of rats. (Here the playwrights are again weaving accounts of Raigō's death taken from such historical tales as Heike Monogatari [Enkyō version], which tells how Raigō's spirit turned into a large rat and ate the Buddhist statues and sutra scrolls of the rival temple, Enryaku-ji.)" (2) |

|

|

|

1. The Actor's Image: Print Makers of the Katsukawa School, Timothy Clark, Osamu Ueda and Donald Jenkins, Princeton University Press, 1994, p. 144. 2. Ibid. p. 146. |

|

WHAT IS RAIGŌ'S STORY? |

|

|

|

Raigō (1004-1084) was an actually historical figure around whom has been spun a fascinating tale. A Buddhist monk of the Tendai sect he was attached to the temple of Mii-dera at Lake Biwa. (1) "Various chronicles relate that by virtue of Raigō's prayers a son was born to the retired emperor Shirakawa (1053-1129), in return for which Shirakawa offered to grant the priest any wish. When Raigō requested the establishment of an ordination platform at Onjō-ji [an alternate name for the temple at Mii-dera], however, the retired emperor reneged on his promise, for fear of the armed monks of the rival Tendai temple Enryaku-ji on Mt. Hiei, who enjoyed a monopoly on ordination. Casting a curse on Shirakawa, Raigō shut himself in the Buddha Hall of the temple and began a fast in protest." (2)

John Stevenson continues the story: "Shirakawa sent conciliatory messages, but Raigo was implacable and eventually starved himself to death. Prince Atsuhisa [the son born to Shirakawa] died soon afterwards. Raigo's vengeful spirit changed into a thousand rats which infested the temple, destroying the Emperor's sacred books and scrolls and doing untold damage." (3) |

|

Above is a detail from a print by Yoshitoshi showing the spirit of Raigo still dressed in his monks robes, but after he has turned into a giant rat. |

|

1. For another example of a print that deals with this same location click here: Kuronushi. 2. The Actor's Image: Print Makers of the Katsukawa School, Timothy Clark, Osamu Ueda and Donald Jenkins, Princeton University Press, 1994, p. 144. 3. Yoshitoshi's Thirty-Six Ghosts, by John Stevenson, Univ. of Washington Press, 1992, p. 68. |

|

|

|

"RATS WERE FORMERLY WELCOMED...AS SYMBOLS OF GOOD LUCK."

|

|

|

|

|

|

There have been times in my life when I had very lean years and for that reason didn't owe any taxes. My deductible expenses far exceeded my income. That is why - and you can call me crazy about this one - I have celebrated those years when taxes were due. Not that I enjoy paying my taxes - who does? - but I do relish those times when I know that I have been prospering - at least to some degree. (I would probably gripe more if I had had to pay them every year, but alas...)

I am telling you this because my attitude has its parallels in traditional Japanese culture. They have been absolutely schizoid when it comes to rats. True rats are pests and do eat into one's assets, i.e., storehouse stocks, but considering the number of years the Japanese suffered from horrific famines there are times when the rat was a welcomed intruder. It meant that one had had a successful year. You don't see many rats when the larder is bare. |

|

|

|

|

|

The quote at the top of this section is from Mock Joya's Things Japanese (p. 41) and the illustration, which was sent to us by our generous contributor E., is from the Ehon Shuyo from 1751. Mock Joya noted that "In many districts, the people rejoiced when rats gnawed the New Year's kagami-mochi or rice cakes, as it was a sign of foretelling good harvests and prosperity during the year." Or, if a rat ate part of an offering made to a family shrine it indicated that the kami or god had accepted the gift.

Daikoku, the god of wealth and good fortune, is often shown accompanied by rats - ergo, rats come with good luck. |

|

|

|

|

|

WHAT ARE YOU? A MAN OR A RAT? |

|

|

|

|

|

Look carefully at the rat in the print above. It isn't a rat at all. It is a man in a rat costume playing a rat's role in a kabuki play. It even has a meshed, netted area at the neck for ventilation. The man who is about to clobber the rat is the actor Ichikawa Danjurō VII in the role of Arajishi Otokonosuke. I love this print by Kuniyoshi. I should. I sold it to a friend of mine, Mike, a number of years ago and he was kind enough to send me an image of it so I could post it here.

Funny thing is that the other day I was rapidly switching channels on my television when I ran across a scene from "Sex in the City" - a program I do not watch. A red-headed, female lawyer was walking down the street and passed in front of a tall man dressed head to toe in the costume of a sandwich. Baloney, you say! I don't know. Baloney, salami...who knows? Anyway, the sandwich was handing out flyers advertising the shop immediately behind him. He and the lawyer had an encounter - a verbal encounter. I found it humorous, but that is another story. What strikes me as absolutely remarkable is the coincidence, i.e., the confluence in my life of seeing two grown men dressed as things which they are not: One a rat; one a sandwich. Clearly there is not much difference between kabuki and modern American theater. |

|

|

|

|

|

Just so you don't think that men in Japan only dressed up in rat suits I have added a detail from a Kitao Masanobu (1761-1816 北尾政演 or きたおまさのぶ) print seen above. This image was created to accompany a 'crazy verse' or kyōka and represents "The Poet Tsuburi no Hikaru" in the ehon Temmei shinsen gojūnin isshu: Azuma-buri kyōka bunko (天明新鐫五十人一首:吾妻曲狂歌文庫) or "Newly Block-cut in Temmei: A Poet of Each of Fifty Poets: A Bookcase of Edo Kyōka". |

|

|

RAT WORDS... errrrr....I Mean MOUSE WORDS... errrrr....I Mean VOLE WORDS! 鼠 |

|

|

Language - especially words - fascinates me. Not that I am particularly good at it, but that doesn't slow me down much. That is why, for example, the Japanese word for rat, nezumi (鼠 or ねずみ), is particularly interesting. Not only does it mean rat, but also mouse and vole. In its simplest form there is no distinction. Nezumi can mean any of the three. "In Japanese, nezumi is the general term for the animals of the order Rodentia, suborder Myomopha. There are no words corresponding to the English 'mouse,' 'rat,' and 'vole,' all of which are called nezumi. The distinction which is most commonly made is by their habitats: ienezumi inhabit...houses and nonezumi inhabit natural environments..." These groupings are divided into smaller categories, but none of these correspond exactly to the Western classifications.

Then there are the odd combinations of nezumi with other kanji characters which denote other creatures, objects and concepts. |

|

|

Squirrel: 木鼠 kinezumi |

Chipmunk: 縞栗鼠 shimarisu |

|

Shrew: 地鼠 jinezumi |

Muskrat: 麝香鼠 jakōnezumi |

|

Guinea pig: 天竺鼠 tenjikunezumi |

Sea cucumber or slug: 海鼠 namako |

|

Porpoise: 鼠海豚 nezumiiruka |

Opossum: 袋鼠 fukuronezumi |

|

Porcupine or hedgehog: 針鼠 harinezumi |

Gopher: 堀り鼠 horinezumi |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Plague: 鼠疫 soeki |

Groin: 鼠蹊 sokei |

|

Petty thief: 鼠賊 sozoku |

Pilfer: 鼠盗 sotō |

|

Unimportant people: 鼠輩 sohai |

Soaked to the skin: 濡れ鼠 nurenezumi |

|

Corrugated iron: 海鼠板 namakoita |

Pyramid scheme: 鼠講 nezumikō |

|

Proliferation: 鼠算 nezumisan |

Pinwheel: 鼠花火 nezumihanabi |

|

Light shower: 鼠の嫁入り nezuminoyomeiri |

Prostitute whistling for customers: 鼠鳴き nezuminaki |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"YOU DIRTY RAT"

|

|

|

|

Years ago I sold a print called "The Rat-catcher" by Cornelis Visscher (1628/9-58).* Above is a slightly cropped reproduction from a photo. Obviously it is not everyone's cup of tea, but for a connoisseur of etchings and engravings it is a masterpiece. Technique aside it remains one of those very strange and unexpected oddities which seldom appear in the European art world. Surely there are many times more images of rats in Japanese art. I can think of quite a few while I am writing this. However, that does not mean that rats haven't played a rather significant role in the psyches of Western artists.

William Shakespeare mentions rats in several of his plays: Shylock speaks of them; the First Witch refers to a "rat without a tale"; Lear mentions them as does Prospero. They even show up in such diverse plays as "Romeo and Juliet" and "The Merry Wives of Windsor". But it is a line for Hamlet that may be the most poignant. Hamlet realizes that there is someone behind the drapery in his mother's room. He believes it is his uncle Claudius, but it isn't. It is Polonius. Right before Hamlet thrusts his blade through the arras he says:

"How now? A rat? Dead for a ducat, dead!"

Many other European and American authors have mentioned rats: Chaucer, Jean de la Fontaine, Tolstoy, Poe, Bram Stoker, Hawthorne, Voltaire, Hugo and Twain - and these are only a few. But two authors in particular come to my mind: Orwell and Browning. Browning sets the stage at the very beginning of "The Pied Piper".

Rats!

Personally the most frightening reference to rats occurs in George Orwell's 1984. Currently I am reading his Homage to Catalonia which is a factual account of the time he spent in Spain fighting against the fascists in the late 1930s. Several times Orwell mentions rats and once he even states that they are the single thing he most detests. "The filthy brutes came swarming out of the ground on every side. If there is one thing I hate more than another it is a rat running over me in the darkness." It was that quote that helped me to a better understanding of Winston in 1984. Orwell was writing about himself. Toward the end of that great novel O'Brien, the interrogator, is going to break Winston's spirit with the one thing he knows he fears the most - rats! He places a cage with rats before him. Winston suddenly realizes its purpose. "...at this moment the meaning of the mask-like attachment in front of it suddenly sank into him. His bowels seemed to turn to water." I don't share Orwell's visceral fear of these animals, but I understand the point. Each of us has our Achilles heel and rats were his.

Rats appear in many other contexts within Western culture. Millard Meiss wrote about the sea-change in European society following the horrific events of the Black Death of 1348/9. And rats in one form or another have entered our collective consciousness through 20th century cinema.

Considering the attention given to rats in the West it does not seem at all surprising that quite a few Japanese artist have also dealt with this subject. Perhaps even the triptych featured on this page will seem a little less exotic by comparison now.

|

|

|

|

*Note that the dates of Cornelis Visscher's life are all over the place. Try looking them up. You'll see. Not only that, but some institutions refer to him as de Visscher. I will get back to you if the art historians ever sort this one out. |

|

|

HOME

HOME