|

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

| Kansas City, Missouri |

|

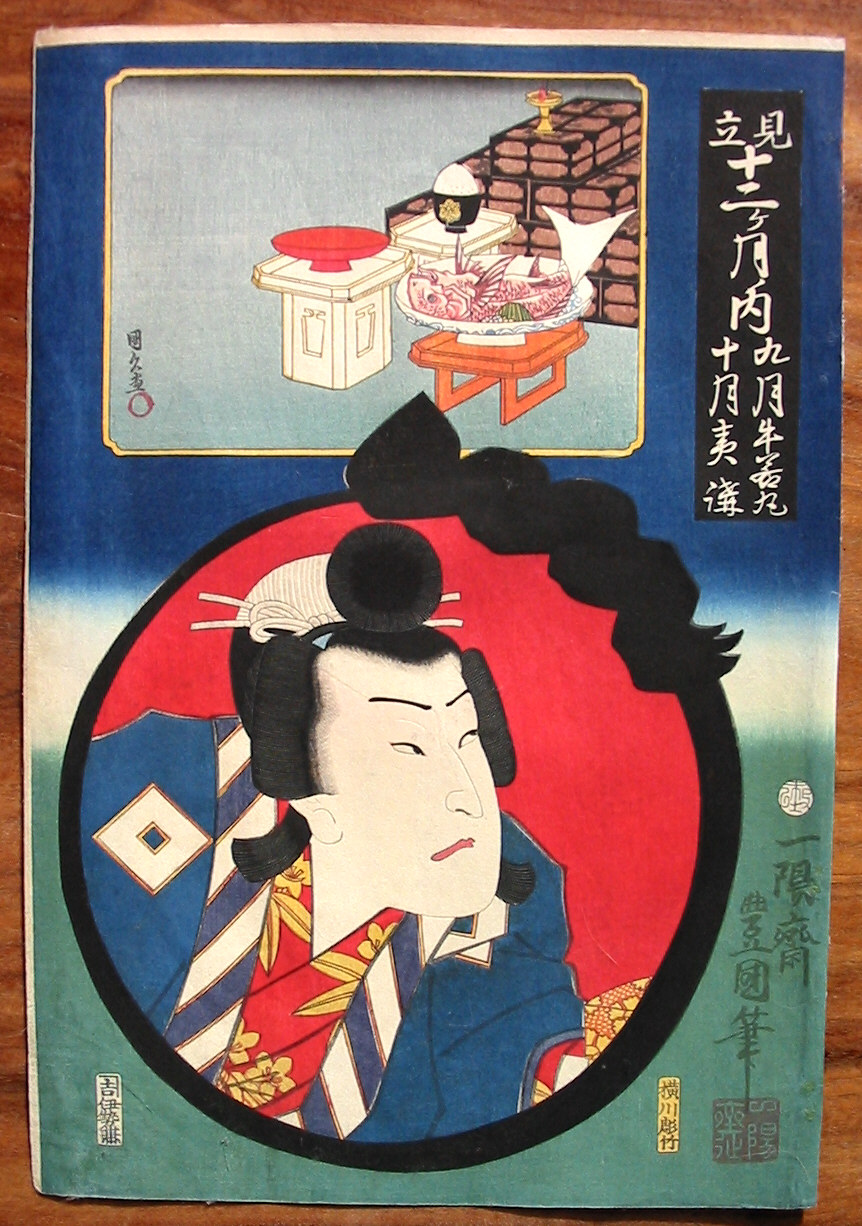

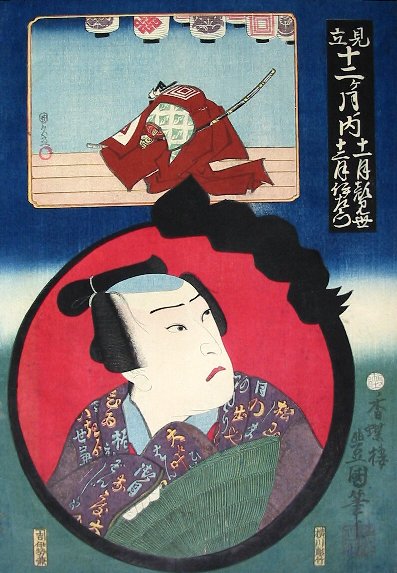

UTAGAWA TOYOKUNI III |

|

三代歌川豊国 |

|

1786-1865 |

|

The large head in the toshidama cartouche represents Ushiwakamaru portrayed by Bandō Hikosaburō V |

|

牛若丸 - 五世坂東彦三郎 |

|

Series: A Selection of the Twelve Months |

|

Mitate juni kagetsu no uchi |

|

見立て十二ヶ月ノ内 |

|

Publisher: Iseya Kanekichi |

|

伊勢屋兼吉 |

|

Carver: Yokogawa Takejirō |

|

Date: 1859, 11th Month |

|

Ansei 6 |

|

安政6 |

|

Size: 14 1/2" x 9 7/8" |

|

Signature: Ichiyōsai Toyokuni hitsu |

|

署名: 一陽斎豊国筆 |

|

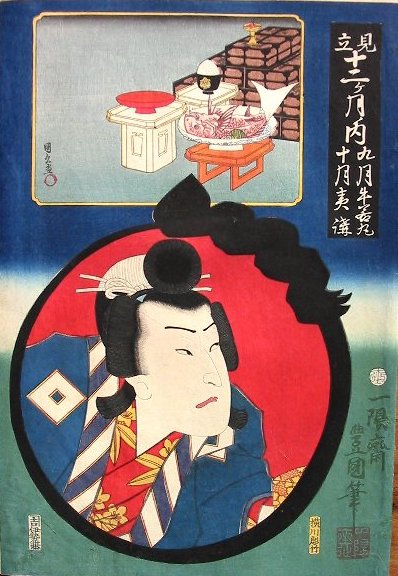

The still life inset at the top of print is by Utagawa Kunihisa (歌川国久). Kunihisa (1832-91) was Toyokuni III's son-in-law. The inset is signed Kunihisa ga (国久画). |

|

There are other copies of this print at the Waseda Universityand in the Hankyu Culture Foundation. |

|

Condition: It would appear that this and the other prints in this series had been bound into an album. That would not only explain the relative freshness of the colors*, but also the areas along the right side of the print where the binding holes have been restored. Other than that the print is in a good state with only very slight areas of distress and with slight soiling. |

|

NO LONGER AVAILABLE! |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

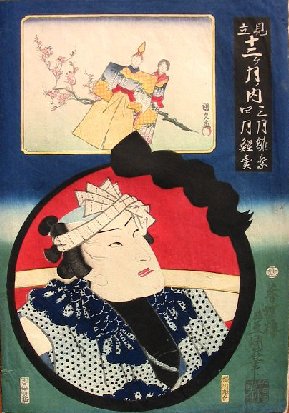

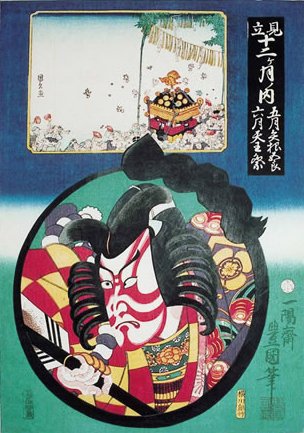

A SELECTION OF THE TWELVE MONTHS |

|||||

|

WE ARE OFFERING FIVE OF SIX OF THIS SERIES, BUT NOT THE FOURTH ONE FROM THE LEFT WHICH IS ALSO THE THIRD ONE FROM THE RIGHT. |

|||||

|

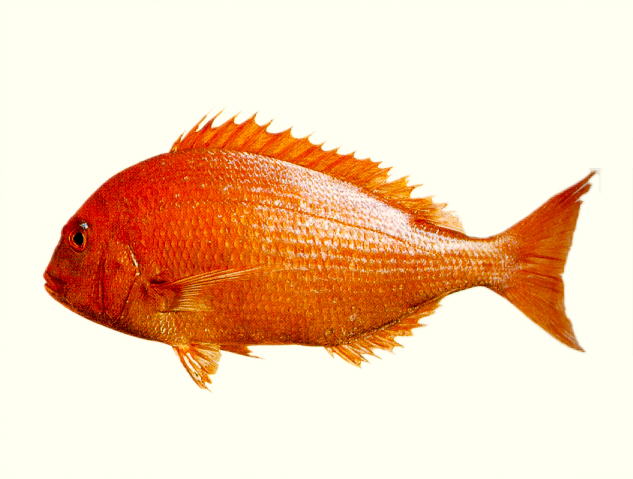

THE RED TAI 鯛 THE SEA BREAM |

||

|

||

|

About this photograph: I searched far and wide to see if I could find a great image of a red tai to show you exactly what they looked like and why the Japanese are so wild about them. In fact, they refer to it as the king of fish. After a fair amount of hunting I ran across this photo and tracked down the persons/organization which owned the rights to its reproduction. Dr. Kenneth Sainsbury of CSIRO (The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation) informed me that the rights seem to be shared by his group and that of a project run by Thomas Gloerfelt-Tarp and Patricia Kailola - funded by German and Danish aid programs - which is trying to provide a large image data base for the identification of different kinds of fish.

Dr. Sainsbury was a 2004 recipient of the Japan Prize for his work on the "science to support the ecologically sustainable use of marine ecosystems." I want to thank and applaud Dr. Sainsbury, Mr. Gloerfelt-Tarp and Ms. Kailola on the great work they are doing and for the use their photograph.

Here is a link to CSIRO'S homepage if you would like to take a look:

(One more point: Dr. Sainsbury noted that this is indeed a photograph of a real fish, but that the background was edited out for the Gloerfelt-Tarp and Kailola project. Thomas Gloefelt-Tarp stated that this was for taxonomical purposes.)

|

||

|

According to Mock Joya, a name which sounds made up, the tai "...is the best and noblest fish....and on all festive occasions there must be tai." Joya notes that there are numerous myths about the tai. "In Chiba Prefecture [千葉県], there is a bay called Tai-no-ura, which is famous for tai. Tradition has it that on February 16, 1222 when Priest Nichiren [日蓮] ...was born at Kominato [小湊] on the bay, lotus blossoms appeared on the sea, and numerous tai splashed about in the sea." As a result the fishermen of this region considered the tai as sacred. They refused to catch them --- or I would assume would throw them back if they were caught --- and even fed them. In time the bay was filled with an overabundance of these fish. This is how this spot got its name, Tai-no-ura (鯛の浦) or Tai Bay. Perhaps this is one of the world's oldest fish reserves --- at least for tai. In another tale the tai have a much greater chance of being caught. In the waters off of Saizaki (幸崎) in Hiroshima Prefecture (広島県) there is an area where the tai are said to float on the surface during the spring tide. While there must be a natural reason for this phenomenon there is also a mythological explanation too. Joya says that when the Empress Jingu set sail for Korea in the year 200 a sailor on board dropped a sake jug into the waters and as a result the tai got drunk and just floated there. Ever since the fishermen of this region go out during the spring tide to catch the "drunken" fish. Hic!

Mock Joya's Things Japanese, by Mock Joya, published by the Japan Times, Ltd., 1985, p. 149. |

||

|

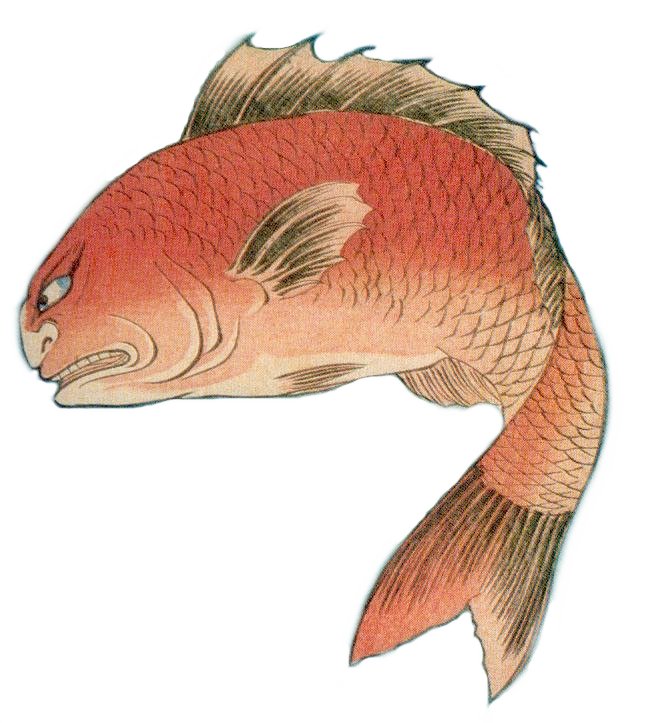

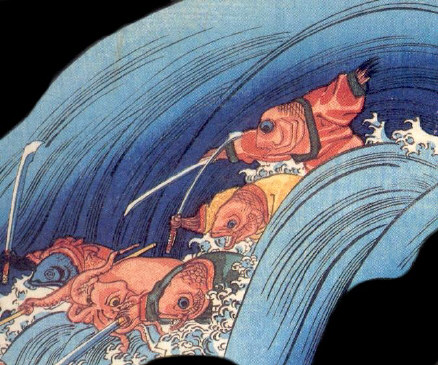

Detail above from a Kuniyoshi print.

|

||

|

THE SEA BREAMNESS OF IT ALL

APROPOS OF NOTHING |

||

|

|

||

|

The other night as I was reading Chapter XI of the Second Part of Cervantes' Don Quixote and there it was...the mention of a sea bream. Not that it has anything to do with the sea bream I have been writing about on this page, but still it was there in black and white on page 533 of my paperback edition. This was too startling a coincidence to let pass without comment.

In the novel Don Quixote is determined to meet the love of his life Dulcinea. Sancho Panza claims that he delivered a message to her in person for his master, but he is lying. He has never set eyes on her. Later Sancho convinces the Don that a particularly ugly, malodorous peasant girl they meet on the road is Dulcinea herself swearing that she is a woman of unmatched beauty. And yet all that Don Quixote can see is the peasant girl as she really is. Sancho is so insistent about her unmatched beauty that his master decides that once again he has been duped by conjurers and has been robbed of his opportunity to bask in her radiance. And yet, that doesn't stop Don Quixote from quibbling with Sancho's description.

"But for all that, Sancho, one thing occurs to me: you described her beauty to me badly. For, if I remember rightly, you said that she had eyes like pearls, and eyes like pearls suit a sea-bream better than a lady. According to my belief, Dulcinea's eyes must be green emeralds, full and large, with twin rainbows to serve them for eyebrows. So take these pearls from her eyes and transfer them to her teeth, for no doubt you got mixed up, Sancho, taking her teeth for her eyes."

The question: Why would Don Quixote refer to a sea bream when describing such a woman? Unsure of the translation and lacking any knowledge of sixteenth century Spanish I looked up the original word in the passage, besugo. Then I checked it against my Oxford Spanish English Dictionary and sure enough it translates as 'red bream.' That led me to wonder about other aspects of this fish. Why would apparently different kinds of sea bream figure so prominently in Japanese culture and in the first great European novel. [I searched the Internet and found at least sixty-one different kinds of sea bream.] Perhaps the answer lies in the etymological root for our word 'bream'. According to the OED 'bream' may have originated in an Old High German verb meaning 'to glitter or sparkle.' If this is true it couldn't be anymore descriptive. Visually its appeal seems to be universal.

|

||

|

|

||

|

CECI N'EST PAS ERRRR, I MEAN CE N'EST PAS UN POISSON! |

||

|

|

||

|

There is a very witty artistic joke to be found in the painting Ceci n'est pas une pipe! by Rene Magritte. It cuts to the core of the meaning of words and/or images. Writ large across the canvas just below the painted image of a pipe are the words of the title. On one level it is a pipe of course, but on another it obviously is not. Following that line of reasoning no picture is the item itself but only a substitute. However, sometimes even within a painting or a print the visual joke is doubled back on us. I mention this because I have long been puzzled by the images of the red tai represented in ceremonial settings. More often than not the fish, which we know has been cooked, still seems to be alive. In the West we have become accustomed to cartooned images of fish with X's over their eyes to indicate that they are dead, i.e., goners. But in Japanese prints and paintings even when we know that they can't still be alive they often seem that way. Why? Well, this morning the answer finally came to me: In a book on Japanese cooking the author spelled it out in no uncertain terms. |

||

|

|

For special occasions, the fish may be shaped before it is grilled with the use of skewers to make it look as if it is still alive and moving to symbolize a vibrant figure bravely swimming through troubled waters. The author adds: Red tai has a silvery red skin, which becomes redder when grilled, and red is regarded as a cheerful, festive colour in Japan.*

|

|

|

*Japanese Food and Cooking, by Emi Kazuko with recipes by Yasuko Fukuoka, published by Lorenz Books, 2001, p. 92. |

||

|

|

||

|

Above is a detail of a print ca. 1843 by Kuniyoshi where he gave each different fish the face of a prominent actor of his day. This one represents Nakamura Utaemon IV as a red tai which was also known as the king of fish. Below is a graffiti portrait of Utaemon IV from another print also by Kuniyoshi, but this one dates from ca. 1847.

|

||

|

|

||

|

The detail above is from an 1853 triptych by Kuniyoshi of Princess Tamatori in the Palace of the Dragon King. |

||

|

|

||

|

EBISU 恵比須 AND HIS SYMBOL THE SEA BREAM |

||

|

|

||

|

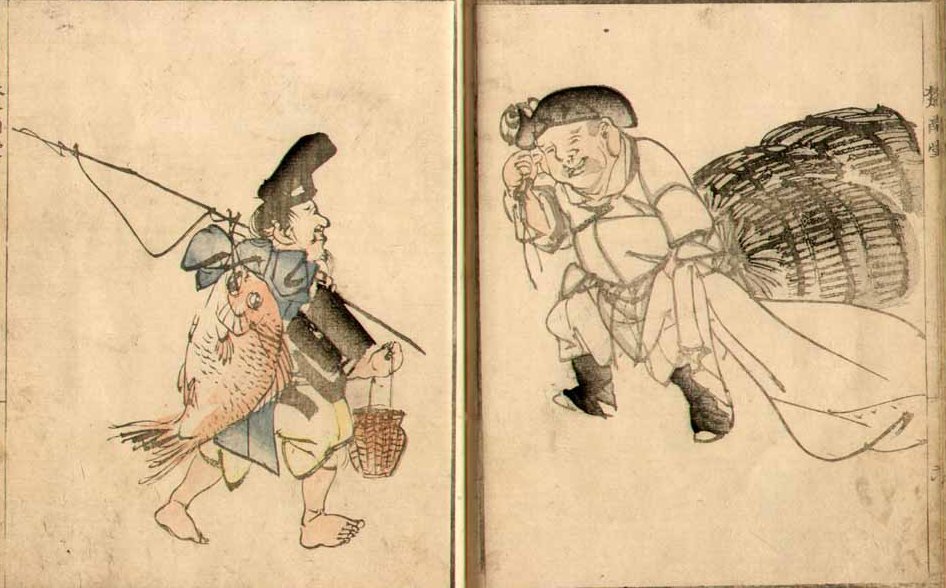

Above is a detail from a print by Toyokuni I. Here two actors are posing as two of the seven propitious gods, Ebisu and Daikoku (大黒). There is a term in Japanese, an ebisugao (恵比寿顔), an Ebisu or smiling face. This god is often identified with his jovial demeanor. That is not immediately clear by the look on the face of this actor, but the fish under the arm and the pole are dead give-aways as to the identity.

One source notes that these two gods are 'buds' and are the closest of any of the seven and that is why they are seen together so often. |

||

|

||

|

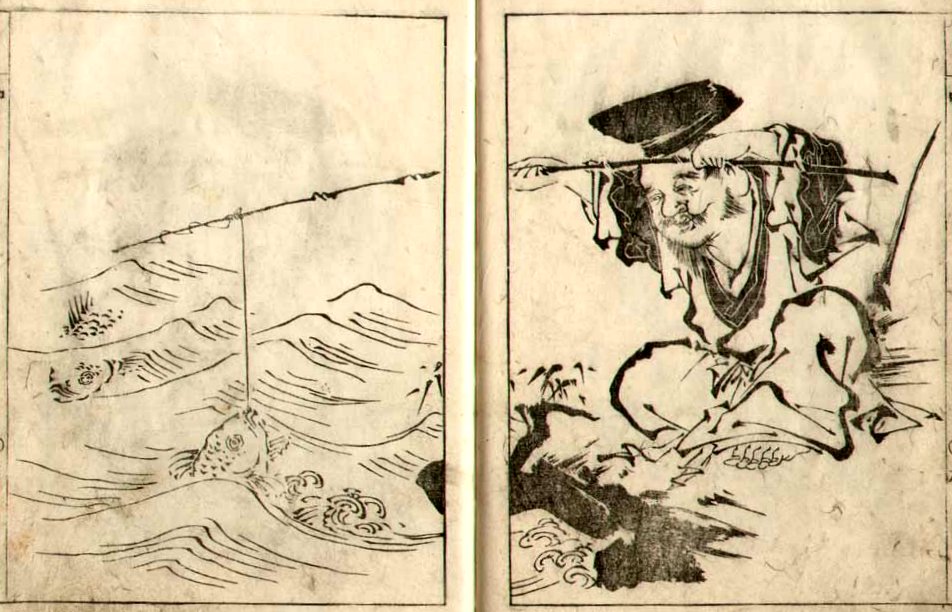

Above is an ehon (絵本) illustration of the frequent pairing of Ebisu and Daikoku. Their attributes made them as recognizable to the Japanese public as the Madonna and Child (マドンナ・アンド・チャイルド) would be to a fifteenth century European. The printing of these woodblocks evokes the Shijo (四条) style. These pages come from the Sonan gafu (楚南画譜) of 1834 by Ōnishi Chinnen (大西椿年: 1792 - 1851).

Note: Jack Hillier in his The Art of the Japanese Book (vol. II, p. 768) states the Chinnen's Sonan gafu was one of "...the best known and most admired of all Japanese books..." |

||

|

|

||

|

At my request a private collector was kind enough to search through his prints and ehons to see if he had any images of Ebisu which he could send to me. Fortunately he found this one which evokes the nature and wit typical of Ebisu art. Like me this collector is surprised by how rarely this god is seen in print form. He put it aptly when he said: "Considering how much good luck Ebisu is supposed to bring, I find it strange that he seems to feature so little!" I couldn't agree more.

There is something remarkably charming about these book pages. Actually there is more than one thing. The use of line on the right hand page evokes a brush-like style much more clearly than can normally be seen in most woodblock prints at this time. It was far more common in black and white ehon illustrations than in single or multiple sheet nishiki-e oban sized prints. This is most clearly demonstrated in the nervous-lined jagged inking of Ebisu's robes. (Hokusai in both his paintings and prints is the master of the nervous line.) The other 'sweet' factor --- and this is strictly interpretive on my part --- is shown by the eagerness of the red tai to be caught by the god of fishing. This is not as clear really in the hooked fish as it is in the envious look of the fish swimming nearby. (Just to fend off critics I will now present the other side: The other fish is looking at the hooked fish and thinking "Whew! Glad that's not me!" But I will stick with my original idea. Remember even some vestal virgins went gladly to their sacrifices. Oh, to be the bream Ebisu would carry around with him tucked under his arm. What tai wouldn't want that?) |

||

|

|

||

|

EBISU AND THE LEECH CHILD FROM DARK TO LIGHT |

||

|

Many gods in many cultures, not just that of the Japanese, started out as wrathful, vengeful, malicious or threatening and over time morphed into something more benevolent and good natured. Such has been the course of Ebisu's 'career' as a deity. What we see now is truly far removed from what this god once was. |

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

THE EBISU FESTIVAL EBISUKŌ 恵比寿講 HELD IN THE TENTH MONTH |

||

|

|

||

|

One of the most intriguing elements regarding this set of prints are the insets by Kunihisa at the top of each. Although the specific pair of months are listed in each of the title cartouches the insets provide a visual clue. The mystery here is to determine what each of them reference.

The Ebisu festival is held twice a year to honor the god of merchants and fishermen. Once in the first month and again in the tenth. "It is said that Ebisu departs on business on January 10 or 20 and comes back with a large fortune on October 20 of the lunar calendar. On the day of his return, or in some districts on the day of his departure, many merchants go to an Ebisu shrine and buy decorated bamboo rakes, symbolic of prosperity, as they may rake in fortune." This custom can be traced back to medieval times, but reached its peak during the Edo period.*

*Japanese-English Dictionary of Japanese Culture, by Setsuko Kojima and Gene A. Crane, published by Heian International Inc., 1991, p. 57. |

||

|

||

|

Above is an 1832 print of a red tai by Hiroshige. Below is a detail from another similar print by Hiroshige illustrating a different type of bream. Neither of these prints is for sale! |

||

|

||

|

EVEN DANTE ALIGHIERI Last night I was reading Canto XXIX of Dante's Inferno when I ran across a reference to the scales of the bream. In this canto Dante describes the shades of the dead souls which are afflicted with every kind of horrific disease. In one passage the author states: As every one was plying fast the

bite I realize that this has nothing to do with Japanese prints or anything else Japanese for that matter, but as I have said prior to doing the research for material on this page I was completely bream-ignorant and now I have found a reference in Dante a thirteenth century European poet. |

||

HOME

HOME