Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画Kansas City, Missouri |

|

INDEX/GLOSSARY

Tengu thru Tombo |

|

|

The orange flowers from the grounds of the Linda Hall Library in Kansas City are being used as markers to new additions and/or corrections for June 1 thru December 31, 2021. |

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

Tengu, Tenjin, Tenjōmayu, Tenjōname, Tenna, Tenshu, Tenshudai, Tenshukaku, Tenugui, Tessen, Tessen, Tetsu, Tetsu kabuto, The Theatrical World of Osaka Prints, Carl Peter Thunberg, Time Present and Time Past: Images of a Forgotten Master: Toyoharu Kunichika 1835-1900, Isaac Titsingh, Tobiuo, Tōji, Tōkaidō, Tōkatsu jigoku, Toko, Tokugawa Tsunayoshi, Tokugawa Yoshimune, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, Tokyo and Tombo

天狗, 天井甞, 殿上眉, 天神, 天和, 天守, 天守台, 天守閣, 手拭い, 鉄線, 鉄扇, 鉄, 鉄兜, 飛魚, 杜氏, 東海道, 等活地獄, 独鈷, 徳川綱吉, 徳川吉宗, 徳川慶喜, 東京 and 蜻蛉 |

|

|

|

One more note about this page and all of the others on this site: If two or more sources are cited they may be completely contradictory. I have made no attempt to referee these differences, but have simply repeated them for your edification or use. Quote anything you find here at your own risk and with a whole lot of salt. |

|

|

TERM/NAME |

KANJI/KANA |

DESCRIPTION/ DEFINITION/ CATEGORY Click on the light green numbers to go to linked pages. |

|

Tengu |

天狗

てんぐ

|

The term tengu literally means 'celestial dog'.

A long nosed fantastic goblin-like creature.

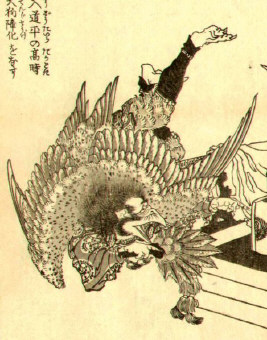

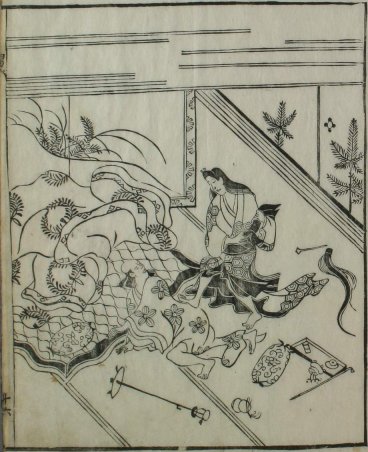

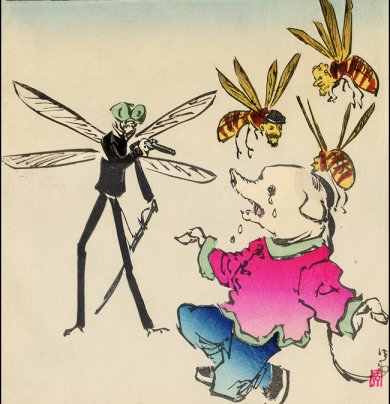

The image to the left was sent to us by E. our generous contributor. It is a detail from the left hand page of a Hokusai book called the Ehon Wakan homare (絵本和漢誉). Thanks E!

In the section on tengu in Asian Mythologies by Yves Bonnefoy (p, 287) it is noted that in the Taiheiki the yamabushi Unkei visits a gathering of tengu on Mt. Atago (愛宕山) where they are "...deliberating the fate of the world." The "...tengu... were thought to be able to tell the future and influence the course of the world."

Another quote from the same source: "With a most original point of view, Tsuda Sōkichi holds that demons, and particularly the tengu, were supposed to have power only over monks who were negligent in Buddhist discipline or services."

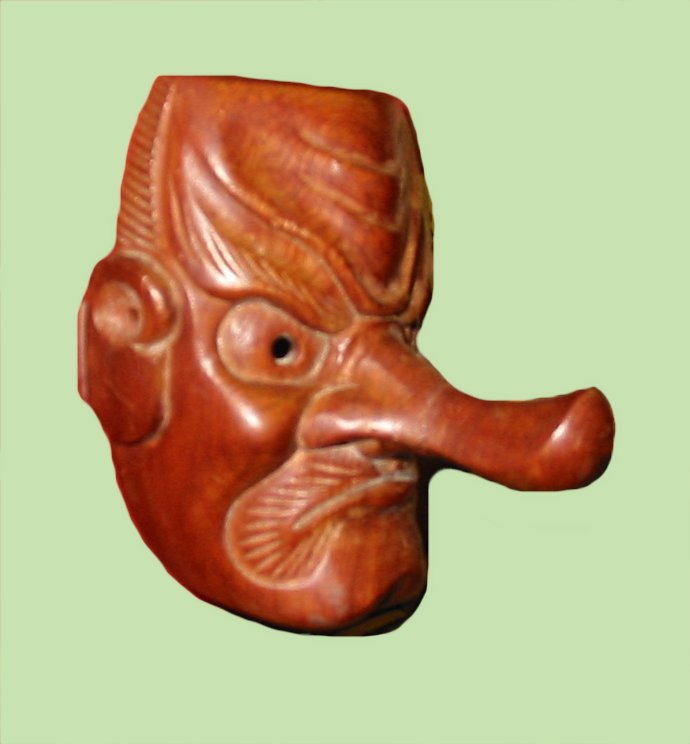

U. A. Casal in his "Lore of the Japanese Fan" notes that among other traits the tengu are "...outspokenly phallic." The image of the carving shown to the left makes this abundantly obvious.. (Monumenta Nipponica, vol. 16, no. 1/2, 1960, p. 58)

Below is a rare, rare, rare image of the birth of a baby tengu. Unfortunately it doesn't do anything to resolve that age old question - "Which came first the tengu or the egg?"

|

|

"In medieval literature they appear prominently as one of the most sinister enemies of Buddhism. They sow seeds of pride in the hearts of those treading the path towards Buddhist illumination. They cause mysterious conflagrations in Buddhist temples. They carry off priests engaged in pious exercises and tie them to the tops of trees."

Quoted from: "Supernatural Abductions in Japanese Folklore", by Carmen Blacker, published by Nanzan University, Asian Folklore Studies, Vol. 26, No. 2, 1967, p. 116.

"The favorite disguise of the goblin [i.e., tengu] was the distinctive garb of the sect of mountain ascetics known as yamabushi [山伏]." Remember: yamabushi is generally translated as mountain priest or Buddhist monk. (Ibid.)

Dr. M. W. de Visser in his article "The Tengu" (published in the Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan, 1908, p. 25) at the very first mentions the number of famous authors and scholars who took the existence of tengu as a given fact - or apparently so. "Even the famous Shintō reformer Hirata Atsutane [1776-1843: 平田篤胤] and the learned novelist Kyokutei Bakin [1767-1848: 曲亭馬琴] made a deep study of this subject." But there were others: Hayashi Razan [1583-1657: 林羅山] , the Buddhist priest Teinin [ていねん], Ogyū Sorai [1666- 1728: 荻生徂徠] and Hiraga Gennai [1728?-1779: 平賀源内]. "By far the clearest and most profound of all the older writers on this subject is Bakin himself." In fact, he was disdainful of the writings of the others. [However, that seems to have been one of his personality traits. He was contemptuous of the scholarship of several of his literary peers.]

Carmen Blacker relates many stories of abductions where the child eventually returns only to be found on a rooftop or in nearly inaccessible rafters. After their return most of these children have diminished mental capacities. De Visser recounts an almost identical story of a ten year old Chinese boy living during the T'ang Dynasty (618-907) who is swept away by a fish-eagle from a celebration at a Buddhist temple. When he reappears he is lying atop a tall pagoda and tells of visiting strange places and eating unusual foods. (de Visser, pp. 30-31) During the 17th century 10 other Chinese boys said they met a man with tangled hair, wings on his back, a beak and a tongue so long that hung down over his stomach. (de Visser, p. 31) There is also a 4th century description of "...a kind of demon in bird shape, who, just as the Japanese Tengu, can change himself into a man..." and set aflame the houses of men who try to harm him. (de Visser, p. 32) ¶ De Visser makes clear that tengu are closely related to the folktales of the Celestial Dog of China. It streaks through the skies, booms thunderously and brings on conflicts between men. He also notes that comets and meteors are often thought to be demons bringing calamities to many different cultures as reported by Frazer in his Golden Bough. ¶ The oldest account of this phenomenon is mentioned in the Nihongi of 720. It was said to have occurred in 637. A Buddhist priest declared that a shooting star was actually the Celestial Dog howling like thunder. (de Visser,, p. 34) The point de Visser is making is that it took a Buddhist priest from China to inform the Japanese who did not know the reason of such things prior to that time. (p. 35) "But there is still more we can learn from the simple words of the Nihongi. At the side of the characters 天狗, 'Celestial Dog,' we find kana, reading 'Ama tsu kutsune' or 'Celestial Fox.' Now the latter is also known as a Chinese demon." (Ibid.) [I know, I know, it's a fox and not a tengu, but we should be able to clear this up eventually.] ¶ In 1446 an encyclopedic work was published which said that Celestial Dog and Foxes are often confused in the literature. "Hirata... points out the great resemblance between the Chinese legends about the Celestial Fox and what the Japanese call about their Tengu." (p. 36) Asikawa Zenan (1781-1849: 朝川善庵 ) said that he knew of three images of a small tengu riding atop a fox. Japanese tengu and Chinese foxes both can take the shape of a Buddha, burn houses, know intimately what is happening both near and far at the same time and take over possession of human bodies. And like certain Chinese werefoxes which possess a special pearl "...whoever becomes a Great Tengu gets a pearl, red as agate. If one holds this pearl before his eyes or ears, he can see or hear all that happens in the three thousand worlds." (p. 37) By the 12th century the Japanese were completely mixing up the lore of the Celestial Fox or Dog with that of the tengu.

The first actual mention of a 'real' tengu came in the 10th century in the Utsubo Monogatari (宇津保物語) or 'The Tale of the Hollow Tree'. "This story shows clearly that in those early days the Tengu was considered as a mountain demon, who deluded people and decoyed them into the depths of the wood." (p. 38) In this case the tengu was disguised as a beautiful young woman playing expertly on a koto. The next mention came in the Konjaku monogatari (今昔物語) of 1077. There are quite a few stories of tengu in the Konjaku. In the first one a tengu hears the singing of a Buddhist text coming from the ocean and is determined to put a stop to it. He follows it to its source which is a stream flowing down Mt. Hiezan in Japan. It is guarded by the Four Kings of Heaven and acts as a privy for a sect of Tendai monks. The tengu is so impressed that he decides to take human form and become a priest. In time he rises in the ranks as a devout follower of Buddha.

The second story tells of a Chinese tengu traveling to Japan to see if the Buddhist priests are as easy to fool there as they are at home. The tengu finds a much tougher crowd - is this a nationalistic comment? - is thwartted by a powerful bishop, beaten by boys and sent a packing in humiliation.

The third story tells of the miraculous appearance of a Buddha in a kaki tree near Kyōto. Crowds of visitors came to witness the Buddha who gave off a brilliant light and rained flowers constantly from the sky. However, one shrewd court minister thought it might be a trick being played by tengu. The minister knew that no tengu could keep up his powers of black magic for more than a week so he went to visit the site on the last day and had the crowds removed. The minister stared at the visitation until finally it fell exhausted to the ground as a large bird with broken wings whereupon a little boy then kicked it to death. In the sixth story - even de Visser doesn't give a synopsis of them all - a tengu tries to tempt a Buddhist priest by taking possession of a beautiful woman. She, i.e., the tengu, is relentless. Finally in desperation the priest implores Fudō Myōō to help him. After Fudō wrangled the possessed woman with his rope she began spinning like a top, bumping into temple pillars. The injured tengu cried out for mercy through the woman's mouth. Compassionately Fudō releases his captive and the grateful tengu leaves the body of the woman who runs away never to bother the priest again. In another case a tengu in the guise of an Amida Butsu appears before a devout elderly priest and his junior monks. The tengu who has surrounded himself with all of the accoutrements of celestial buddhahood - the lotus throne, the five glorious colors, Bodhisattvas, angels, blinding light - sweeps down and carries off the elderly priest supposedly with the intent of taking him to the Western Paradise. Several days later and some distance from the abduction a priest was walking through the woods and heard moaning and groaning. He looked up and saw the naked form of the elderly priest tied near the top of tree. He climbed up and rescued the old man only to be scolded by him. The devout priest had been told by the tengu/Amida to wait there as part of his journey to paradise. "The bewitched priest was raving mad and died after a few days. He had been deceived by Tengu because he had no knowledge and did not understand the difference between the work of demons and the world of... [Buddhist principles]." The point: Tengu are nettlesome creatures which are often at war with Buddhists. They disguise themselves as bonzes, nuns, bishops and even Buddhas to trick the most gullible - especially among the clergy. Defense: A knowledge of the true ways of the Buddha will be your best protection.

By the 12th and 13th centuries the tengu had branched out mischievously to torment members of the Imperial Court and the Court was fighting back, but not always successfully. (de Visser, pp. 44-5) "As in the Chinese story of the Konjaku monogatari, this Tengu is an angry ghost of a priest, who probably had suffered some wrong from the Throne and had died in anger." (p. 45) But the struggle between the tengu and the Buddhist clergy didn't let up. Occasionally wayward priests came back as one of those foul smelling tengu after he died. "In these legends we read for the first time about the Tengu-road, as one of the punishments of hell for vain and hypocritical priests." (p. 46) In many cases humans only seem to be possessed by tengu to act as vehicles for dead priests.

In the story of Yoshitsune, the hero of the Battle of Dannoura in 1185 when the Minamoto beat the Taira, he is said to have been taught in martial skills by the tengu. How else could he have performed so remarkably? Do you have a better explanation?

Numerous stories about the travails of the 77th Japanese emperor, Go-Shirakawa (1156-58: 後白河) refer to vengeful relatives who torment him as ghosts/tengu. (pp. 49-50) But Shirakawa was not immune to the same issues: "The Gukwanshō [1220-25: 愚管抄] contains the following story: - In the year 1196 the ghost of the Emperor Go Shirakawa , who died four years before, possessed two women and a priest, through whose mouth he spoke and ordered the people to worship him." The 82nd ruling emperor Go Toba [1183-98: 後鳥羽] exiled the first two, but when the order was repeated again he began to think that it just might be the late emperor's ghost speaking. Just as he was about to follow the dictate he received a letter from a bishop who told him that it was more likely the work of a fox or tengu. As everyone knows those creatures love being worshipped. The bishop noted that many people in the capital had already started worshipping the dead emperor in anticipation that the living one would do the same. The bishop pointed out that if Go Toba went ahead with his plans he would join "...all kinds of low people... [like] such fools as miko, kannagi [巫] (female sorcerers) and dancers of the saru-gaku (monkey-dance). If such things happen, the world will come to an end." Whew! Fortunately Go Toba took the bishop's advice - and the world didn't end. (de Visser, p. 50) In 1184 tengu were blamed for Shirakawa's problems. (p. 51) In another case Shirakawa is told that about 90% of contemporary priests fail to follow the way of the Buddha properly and therefore are apt to take the tengu-road. (p. 52) That is a lot of errant priests and hence proto-tengu. "Proud Nuns become Nun-Tengu, the priests Priest-Tengu. Although their faces are those of Tengu, their heads are those of nuns or priests, and although they have wings at the arms, yet they wear something like a dress and around their shoulders hang scarves (kesa). When ordinary men, who are proud, become Tengu, they have Tengu faces, but on their heads wear the eboshi (a cap formerly worn by nobles..." etc. When women became tengu among other habits they continued was tooth blackening. [See our entry on ohaguro.]

By this period tengu has taken on new skills in the telling; incendiarism and the full capacity to know both the history going back 100 years and a clear view of the future for the same length of time. Another new phase was the abduction of children with no purpose other than to distress the parents. Generally the children are returned much the worse for their adventure. Ill and near death the tengu had fed the children what they convinced them were treats but in fact were nothing more than dung. (p. 57) [In Paris once I ordered andouille. The waiter tried to dissuade me, but I persisted. Ate a little bit and now know how the abducted children must have felt. And to think there were no tengu dining with me.]

Now, I think I already mentioned the fact that Buddhist priest could come back as tengu. However, what I haven't mentioned is that there are 'good' demons and bad ones. Priests who were proud and ambitious and didn't really follow the way of Buddha would come back as the bad ones. The ones who erred in the same way, but still believed in the Buddhist scriptures came back as good one, i.e., good tengu priests, who would continue to study the way and act as protectors of Buddha. (pp. 59-60)

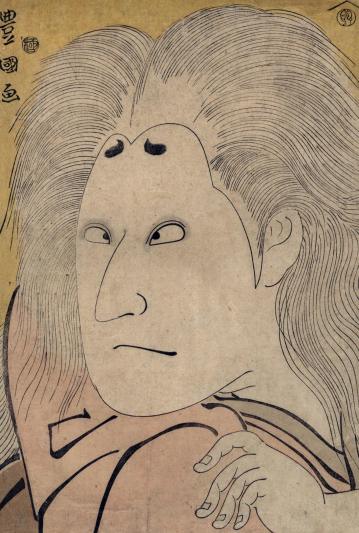

In the Genpei Seisuki (源平盛衰記) the god of Sumiyoshi appears before the retired emperor Go Shirakawa telling him that he difficulties with the Hieizan priests is actually the fault of heavenly devils or temma (天魔). When asked about the nature of these devils the god gives quite a list. Among these are priests with great learning who become great tengu and of those of lesser knowledge small tengu. Those with no knowledge or understanding go on the animal-road or chikushōdō (畜生道) after death. [Chikushōdō can also mean incest.] They come back as horses or cows and are beaten every day. The god continued: "In the middle ages there lived in Japan a bishop whose name was Kakimoto no Ki, a pupil of Kōbō Daishi. He was also an intimate friend and nearly his equal. But he grew proud of being the possessor of the Great Law and became the first Great Tengu of Japan, Tarōbō of Atago-san. As there are many proud men in the world, a great number became Tengu, and on all the mountain peaks of the country, twenty, thirty, fifty, a hundred or two hundred of them are assembled." [Kakimoto = 桓本: Kōbō Daishi = 弘法大師:Tarōbō = 太郎坊: Atago-san = 愛宕山] The image shown above is a detail from a print by Kunisada showing Tarōbō as both priest and tengu as displayed on a hanging scroll. (de Visser, pp. 51-3) Notice the kongōsho or double vajra he is holding in his left hand.

In the early 14th century Yoshino shūi (吉野拾遺) the long nosed tengu makes its first appearance. "Formerly they were always described as having kite's beaks. No doubt the long nose is only a humanized bird's bill. As is very often the case with animal-shaped gods and demons, there is a general tendency toward taking the human body. First of all the Tengu were kites, then they became men with the head of a kite, thereupon they had only a kite's beak, till at last the latter changed into a long nose." (p. 61)

3 mountains known for their concentration of tengu are Atago, Ōtake and Kimpusen. (p. 64) One of the repetitive themes of tengu life was that of a gathering where they would drink balls of red hot iron, writhe in agony, burn up into a pile of ashes and then after a short period be reconstituted only to continue their original activities. Hollywood could do no better than that. Also, many of the stories of strife and warfare are explained as being provoked and promoted by tengu who by this time are the vengeful spirits, i.e., of famous men. There is less emphasis on anti-Buddhist activities although monastery or temple fires are almost always blamed on tengu - they couldn't possibly be an accident or arson caused by a mortal. Losses on the battlefield were clearly caused by tengu armies in disguise.

De Visser tells us that in the Ainoshō (埃嚢鈔) of 1446 it states that "...all distinguished officials and priests become Tengu on account of their proud hearts." (p. 67) On a totally different matter: one theme seems to pop up again and again and that is the rivalry between the Buddhist monks of Hieizan and Miidera. For example, when two boys disappeared (p. 68) from Miidera the monks at Hieizan were blamed when in fact it was the - you guessed it - tengu. But that is only one theme. There are plenty more where that one came from. Too numerous to list.

In the 17th century a story about Tarōbō of Mt. Atago appears in the Honchō Jinjakō (本朝神社考): "Hosokawa no Katsumoto [細川勝元] (1430-1473), who had no children, prayed on Atago-yama to the Great Tengu Tarōbō for a son. His prayer was heard, and Masamoto [政元] (1466-1507) was born. This son, who was a Tengu, became kwanryo (first minister of the Shōgun) in 1494, and having been murdered in 1507, caused a curse after his death. In order to smooth down the Tengu ghost a temple was built in his honor." (p. 70) As I am sure you must realize by now this story is based on the lives of real people. Sibling rivalries between Masamoto's three adopted sons was the cause of his death - unless, of course, you are inclined to think it was tengu doings.

As noted above de Visser mentioned three mountains populated by tengu. That was on p. 64, but on p. 70 me adds to the list these mountains: Taisen, Hiko, Kurama, Hira, Hieizan. Chances are where there are mountains there are tengu. (A cautionary note: Whenever a mountain is named it might not be the one you are familiar with. Turns out there are often several mountains in several provinces with the same name. I suppose that would be like trying to find Springfield, U.S.A. Supposedly there are a ton of them. 35? 38? I mention this because sometimes it is difficult sorting out the true local of a place shown in a print or mentioned in the literature.)

Razan, a Confucian scholar, who was mentioned above, believed "...that the Tengu evidently are ghosts of the dead who have become demons (悪鬼). He enumerates the principal ones, and puts in the first place the 'Bishop of Kurama' (who instructed Yoshitsune), Tarō of Atago, and Jirō, of Hira-yama. As to their shape he says: 'Sometimes they become foxes or boys, sometimes they fly in the shape of doves, or come among men as Buddhist priests or yamabushi; sometimes they change themselves into demons or Buddhas or Bodhisattvas. They change luck into calamity, and order into confusion. Now they cause fire, now war." (p. 71)

In the 18th century the first stories appeared of people dropped from the sky by tengu.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Tenjin |

天神 てんじん |

Literally the term tenjin means 'Heavenly Deity'. Now it is identified with the deified spirit of Sugawara Michizane (管家: 845-903). Within Japan his spirit plays somewhat the same role among Shintō believers as that played by the patron saint in the Catholic Church, but here he is the patron of scholarship and calligraphy.

He was also given the posthumous title of Karai tenjin (火雷天神) or god of fire and thunder and is often portrayed surrounded by or directing bolts of lightening. |

|

The Kitano Shrine (北野天満宮) in Kyōto was established in 947 in honor of Sugawara Michizane's spirit. On the 5th day of the 8th month of 987 they celebrated the Kitano matsuri for the first time and was meant to appease Michizane's wrathful spirit. It is still celebrated today.

Above is a photo of that shrine posted by Masahiko Nagao at panoramio.com.

"Kitano Tenmangū was first founded in 947, and became established as a fully fledged miyadera by 959. It was staffed by shasō, and included in the list of twenty-two shrines from 991 onwards. The deity enshrined here, known as Tenman Tenjin, was a complex combinatory divinity, including the deified 'angry ghost' of Sugawara Michizane... a kami (Tenjin himself), an Indian deity (his full name, Daijizai Daitenmanjin, includes a reference to Daijizaiten, i.e. Śiva), and a bodhisattva, Kannon." (Quoted from: Buddhas and Kami in Japan: Honji Suijaku as a Combinatory Paradigm, p. 28) "Miyadera (宮寺) were temples, founded and administered by Buddhist monks, where the main object of worship was a kami. They differed from shrine temples... in that there was no established priestly clan conducting its own kami rituals at a separate shrine. They also differed from temples, in that monks of miyadera, known as shasō or 'shrine monk,' could marry and pass their positions on to their sons. Although they were run by monks,miyadera also had kami priests (negi, kannushi), but these were of subordinate rank, and had minor functions even in the rituals; only the shasō, for example, were allowed to enter the inner sanctuary of the temple. [¶] Miyadera were not placed under the control of the Ministry of Kami Affairs, and were not included in the list of shrines that received court offerings... [in] 927. However, half a century later... the largest miyadera were included.... This once and for all defined them as shrines, and incorporated them in the court system of kami ritual." (Ibid., p. 26)

"The Toyotomi were... responsible for the rebuilding of the Kitano Tenmangū in Kyoto in 1607. Founding this shrine, dedicated to the spirit of the exiled Heian aristocrat Sugawara Michizane, was an act of piety also designed to pay handsome political dividends in the uncertain years following the Tokugawa military ascendancy at Sekigahara in 1600. (Quoted from: Architecture and Authority in Japan by W. H. Coaldrake, p. 178)

W. G. Aston in his Shinto: The Way of the Gods refers to Tenjin as Temmangu (天満宮) which is also the name of the shrine itself. In 1905 Aston reported that Tenjin was one of the most revered gods in Japan. In 1825 there were approximately 25 shrines devoted to this god alone in the Edo area.

"The ox is the mount of several holy men and sages... [including Lao-tzu].... In exile Michizane frequently rode an ox and he was very fond of the blossom of the plumtree. He is often depicted riding through the air on his ox and accompanied by a blossoming plumtree, also defying the laws of gravity." (Quoted from: The Animal in Far Eastern Art... by T. Volker, p. 129) There is a story that right after Michizane died that "As his remains were beng taken to the burial ground, we are told that the ox pulling the cart stopped just outside the northeast corner of Dazaifu. Since it could not be made to budge farther, Michizane was interred there, at what became the site of the Dazaifu Temman Shrine. The story about the ox is probably a later fabrication, but Michizane may well have been buried at what is now the shrine...." (Quoted from: Sugawara no Michizane and the Early Heian Court by Robert Borgen, p. 304) Below is a statue of an recumbent ox at the shrine where Michizane was said to have been buried. It was taken by Fg2 and posted at commons.wikimedia.

The Dazaifu Tenjin was one of the 66 holy sites, the rokujūroku-bu (六十六部), visited by pilgrims on their circuit.

Michizane had a servant named Oimatsu ('Old Pine') who followed him into exile. This is somehow the inspiration for one of Zeami's Nō plays. In an oracle from 947 it is revealed that "...Michizane wished to be worshiped at Kitano, where pines would grow. Soon afterwards, thousands of pine trees are said to have miraculously 'grown' (oinu) there overnight, and hence it became the site of the still popular Kitano Shrine." (Borgen, p. 294) There is a poem in which Michizane is said to have chided a particular pine tree in Kyōto. The pine was so ashamed of being scolded d"...that it 'followed' (oinu) the plum and flew to Dazaiful. The Old Pine Tree (Oimatsu), a noh play by Zeami (1363-1443) hints at this story, and it became the key to the elaborate plot of the puppet play, The Sugawara Secrets of Calligraphy, first performed in 1746." (Ibid.)

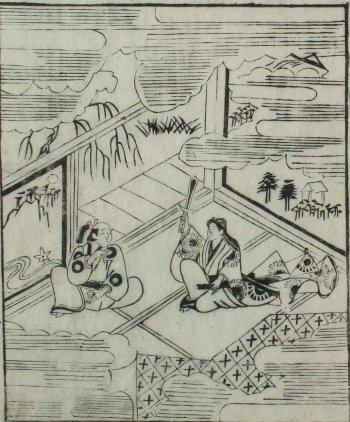

Above is a detail from a print by Sadahide showing Michzane riding an ox. Behind is an old pine. Is the old man holding the tether Oimatsu? That's our guess. This image was sent to us by Eikei (英渓), our great contributor.

"In medieval times, the pine was added to the plum and cherry to form a triumvirate of trees associated with Michizane." (Ibid., p. 291) "As Michizane was about to [go into exile], he is said to have addressed the plum tree in his garden with what would become his most famous waka..." (See the poem below - also from Borgen, p. 290)

When the east wind blows, Let it send your fragrance, Oh plum blossoms. Although your master is gone Do not forget the spring.

Below is a photo of a clearly highly regarded blossoming plum tree at Dazaifu posted at commons.wikimedia by David Chart.

"During the Middle Ages, [Tenjin] became the patron saint of yeast for sake brewers and is still venerated in the weaving world of Nishijin district of Kyoto (Ōtoneri guild)." (Quoted from: Japanese Capitals in Historical Perspective: Place, Power and Memory in Kyoto, Edo and Tokyo, p. 163) |

||

|

|

||

|

Tenjōmayu |

殿上眉

てんじょうまゆ |

Court or palace eyebrows - These are the artificial eyebrows added near the top of the forehead after the actual eyebrows had been shaved off. This was a common practice for the highest ranking courtiers during the Nara and the Heian periods and probably originated from Tang dynasty practices.

Tenjō means 'court' and mayu means 'eyebrows'. Plain and simple.

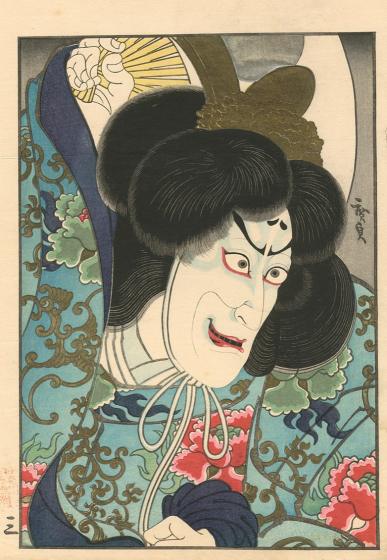

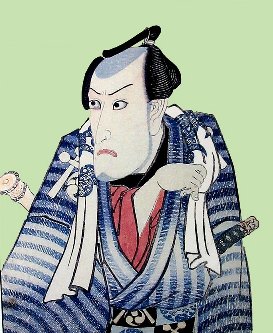

Above is a portrait of Ichikawa Ebizō V as Moriya Daijin. It is by Hirosada and dates from 1849. It comes from the Eikei Collection.

The image from the Lyon Collection to the left is by Toyokuni I from ca. 1795. It represents Sawamura Sōjūrō III as Konomura Ōinosuke [此村大炊之助] from a very fanciful kabuki play. The figure represent a fictional character from the Ming dynasty, but the use of the court eyebrows is basically an artistic conceit. |

|

Tenjōname |

天井甞

てんじょうなめ |

A ceiling-licker, a kind of monster - "Whereas the kappa has a long and storied presence in local folklore, other yokai have much more dubious origins. In Mizuki's catalogs, for example, there is an ugly monster called a tenjōname, or literally 'ceiling licker': a tall, bony creature with frilly hair and an extraordinarily long tongue. Mizuki's illustration shows it seemingly suspended in mid-air, licking a wooden ceiling. 'When there is nobody around in an old house, temple, or shrine,' Mizuki writes this monster 'comes out and licks with its long tongue ... if they found stains on the ceiling, people in the old days thought it was the work of the tenjōname.' As an explanation for the otherwise unexplainable, the tenjōname fulfills a common function of the monstrous." Quoted from: The Ashgate Research Companion to Monsters and the Monstrous, pp. 144-45

"...some scholars think that the tenjōname was simply fabricated by Sekien? Was Sekien's invention then introduced into oral tradition and village folklore to become, centuries later, an explanation for stains on the ceiling?" (Ibid., p. 145) |

|

Tenna |

天和

てんな |

The reign era 1681-84. This period "...though brief, forms one of the peak eras of Japanese popular culture. In literature Saikaku created the modern novel out of the amorphous kana-zōshi, while in ukiyo-e, Moronobu reached his ultimate in book illustration and in albums of print masterpieces ranging from scenic/genre views to legendary tales and bold erotica.... With Tenna came a combination of economic stability and widespread education, which resulted in an affluent, appreciative audience for new trends in art and illustration. Quoted from: "Historical Eras in Ukiyo-e" by Richard Lane in Ukiyo-e Studies and Pleasures, Society for Japanese Arts and Crafts, the Hague, 1978, p. 28.

The book illustrations here were published during this period. Both appeared in 1682. The one to the left if from Ihara Saikaku's Life of an Amorous Man. The one above is from the Sange monogatari. |

|

Tenshu |

天守

てんしゅ |

This word is not found in all Japanese-English dictionaries, but it is found in some, like Nelson. Basically it is listed as the same as tenshukaku, found below. In Castles of the Samurai: Power and Beauty they do make a distinction in the glossary on page 103. "Tenshu: The main tower of the castle. Tenshu are usually one of four styles: independent (doku-ritsu-shiki), attached to a small tower (fukkugo-shiki), connected to one or more minor keeps by a corridor (renketsu-shiki), or one large tenshu and three or more smaller ones (ren-titsu-shiki)."

The photo to the left is of the tenshu of Osaka Castle posted at Pinterest by Guiddoo. The interior of the tenshu at Hikone Castle, the rafters, can be seen above, It was posted by Joel Abroad at Pinterest. |

|

Tenshudai |

天守台 てんしゅだい |

The stone base of the main tower or tenshu. |

|

Tenshukaku |

天守閣

てんしゅかく |

The main castle tower or donjon. The image at the left comes from a 1928 print by Hiroshi Yoshida (吉田博) of Himeji Castle (姫路城).

"Himeji Castle contains more than 80 buildings. The main keep, the tenshukaku, is in the center of the castle. It has six stories, with five projecting roofs. From the tenshukaku, the castle residents watched for enemies. The tenshukaku was also a storeroom for weapons and the place to which everyone retreated when the castle was attacked." Quoted from: Life in a Castle by Kay Eastwood, p. 30.

"The large-scale construction projects of the Tokugawas were as extravagant as their ambitions to rule. Thus the first half of the seventeenth century witnessed the erection of not only the Nikkō Toshogu, the fabulously ornate mausoleum enshrining Tokugawa Ieyasu, and the Kan'eiji, the temple which became the center of the Ieyasu cult in Edo; it also saw the dramatic and monumental rebuilding of Edo Castle and of the entire city. This ambitious project included the elaboration of a spiraling moat system around Edo Castle and the building of massive gateways (mitsuke), which not only protected the approaches leading to the castle but also exuded Tokugawa power. The five-tiered donjon (tenshukaku), the most awesome structure in the castle compound, was completed in 1607 and then richly embellished through construction projects in 1622, 1637, and 1653. Soaring to a height of over fifty meters, it was the largest tenshukaku in Japan: a fitting centerpiece for a complex which was about twice the size of the next largest compound in Osaka. ¶ The Great Fire of 1657 that razed some 60 to 70 percent of Edo and much of the castle consumed the tenshukaku and put an end to the early-modern period of monumental building. To be sure, the bakufu restored the main structures within the castle compound and continued to do so after the numerous fires that plagued both Edo and Edo Castle through the Tokugawa period; but the tenshokaku, a singularly symbolic ornament, was never rebuilt." |

|

Tenugui |

手拭い

てぬぐい |

(Hand) towel - "A distinctive clothing accessory of the Edo townsmen is the tmugui, a cotton hand-towel, commonly worn around the neck or used as a headband (hachimaki) by the tattooed street-knights (otokodate) and firemen (tobi-no-mono). These towels, known as mameshibori tenugui and frequently worn by the heroes of the kabuki stage, consisted of plain white cotton dyed with the characteristic blue polka-dot pattern resembling rows of beans (mame) and produced by the tye-and-dye method (shibori)." Quoted from: Irezumi: the Pattern of Dermatography in Japan by Willem R. van Gulik, p. 82.

The image to the left is of 3 contemporary Kamawanu tenugui. It was posted at Flickr by Tatsuo Yamashita. Kamawanu is an area of Tokyo which specializes in the production of these multi-purpose towels. |

|

Bashō wrote a fine haiku which mentions a tenugui. The translation is by David Landis Barnhill.

At the inn on the journey burning pine needles to dry my handtowel: the cold

Detail from a Harunobu print ca. 1770 showing a young woman preparing for her bath with a tenugui hanging on a stand nearby.

"Japanese towels include the furoshiki, for putting on the floor to dry the feet, and the tenugui, a towel that is wrung out after absorbing water from the user's body." Quoted from: The Bathroom Companion: A Collection of Facts About the Most-Used Room in the House by James Buckley, Jr.

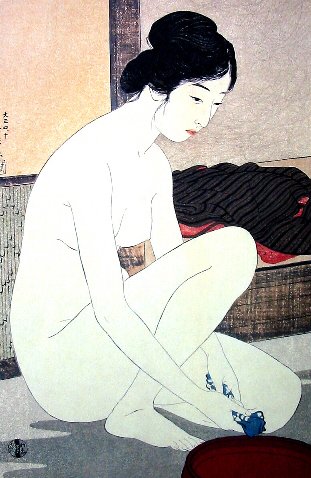

Above is a detail from a print by Goyo from 1915 showing a woman wringing out her tenugui.

"During the dance Musume Dojoji the actor coyly holds the center of a hand towel, known as a tenugui, in his mouth and then opens the towel out to display to the audience his own personal crest. Later in the play the dancer and the priests who watch the dance will interrupt the drama to throw some of these towels imprinted with the crest out to the audience as souvenirs of the occasion." Quoted from: Kabuki: A Pocket Guide by Ronald Cavaye, p. 124.

"Bathing etiquette in Japan is quite simple. Take your own soap and towel, and a washcloth or small hand towel called tenugui (tay-nuu-gooey), which is used to cover your genitals when walking around and for scrubing and sponging off." Quoted from: Etiquette Guide to Japan: Know the Rules that Make the Difference! by Boye Lafayette De Mente, p. 66.

"...to speak of the tenugui (literally, 'hand- wiper') as a towel is to convey a very false impression of the little blue-and-white linen kerchief which these shell-seeking ladies twist into the daintiest coiffures conceivable, not so much to shade their complexions as to preserve the gloss and symmetry of the achievements that their hair-dressers have turned out for the occasion." Quoted from: Japan [And China]: Its History, Arts and Literature by Frank Brinkley in 1904.

In Marriage in Contemporary Japan by Yoko Tokuhiro (p. 108) mentions that traditions have changed in courtship and marriage and cites events in small villages. "He [i.e., Fumiko] remembers clearly that newly wedded couples often visited their neighbours, bringing a gift of tenugui (a hand towel) in order to obtain acceptance and recognition in becoming village members."

Detail from a Kunisada print showing an actor in an off-stage moment.

"One form of traditional storytelling is rakugo, in which a performer, the Rakugo-ka, sits onstage on a purple cushion wearing traditional clothes and portrays many different people using only a folding fan (sensu), handtowel (tenugui) and different voices." Quoted from: Key Into Japan by Sally Heinrich, p. 70.

In Japan from A to Z: Mysteries of Everyday Life Explained (p. 111) by James and Michiko Vardaman there is a discussion of the various uses of the tenugui. "Whether it [is] a person be a construction worker, a noodle vendor, or even a homemaker picking up around the house, he or she is as likely as not to have a piece of cotton cloth wrapped, tied, or draped around the head to mop up sweat and repel dust. Nowadays distributed as advertisements of sightseeing spots, tenugui are also still used by kabuki actors to indicate they are playing certain types of roles. They are also used by the people who carry portable shrines at festivals to indicate their affiliation with a sponsoring group, a professional association, or even a company. Even hikers use them for a very simple task — to wipe away perspiration."

Tenugui were used as prop/accessories during the Bon festivals. Judy van Zile in her essay 'Japanese Bon Dance Survivals in Hawai'i (1982)' in I See America Dancing... (p. 77) says: "Tenugui (small towels approximately the size of hand towels), with a special design for each temple or Buddhist sect, are given to members of the participating clubs. At some temples they are given to all participants, and at others to anyone who wishes to make a donation to the temple. At some temples, for an additional donation one can have his or her name written on the towel in Japanese lettering."

Sexy detail from an Eisen print.

"The temple Nishinotaki Ryūsuiji on Shodoshima has, as one of its sacred amulets, a lucky hand towel (mamori tenugui) that serves many purposes, bringing its owner, according to its wrapper, these 'wonderful benefits':

Traffic safety for people who drive cars Prevention of danger for those with dangerous occupations Acquisition of wisdom for those going through the education system

It also promises relief from various pains and illnesses, instructing those with such problems to do the following:

For those with headaches or unable to sleep: please place this under your pillow, and rest. For the sick: please place the towel on the spot that hurts, and rest. For those who are injured: immediately wrap the wound with the towel."

These acts should be accompanied by the appropriate mantra recited 21 times. Source and quote from: Practically Religious: Worldly Benefits and the Common Religion of Japan by Ian Reader, p. 193.

Professor Leiter in his Historical Dictionary of Japanese Traditional Theatre gives two interesting references to tenugui (pp. 398 & 202):

1)"TENUGUI. The oblong cotton 'hand towel' commonly carried by numerous kabuki characters and used as one of the actor's most versatile hand properties. They come in varying sizes and patterns, often bearing the actor's mon, and their size is about three feet long and a foot wide. They serve as hachimaki, as cloths to mop the brow, fan oneself, wipe away tears, be worn as hoods, etc." 2) "KUCHIBARI. The small pin protruding near the upper lip of bunraku's female puppet heads. The puppeteer allows the puppet's sleeve or hand towel (tenugui) to snag on the pin during emotional scenes, which gives the impression that the character is biting on the cloth to restrain her tears." |

||

|

|

||

|

Tessen |

鉄線

てっせん

|

The passion flower or clematis was used as a family crest for several families "...on the basis of its beauty alone..." "The inner disc of the blossom resembles a chrysanthemum, a likeness which Japanese draftsmen high-lighted in many of their versions of this motif." Quotes from: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, pp. 66.

We have added two photos of the tessen provided generously by Shu Suehiro at http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm.

|

|

Tessen |

鉄扇

てっせん |

An iron-ribbed fan - The image to the left is from the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco. We first found it at Wikipedia. The curatorial files of that museum note that is also referred to as a gunsen (軍扇). They say: "In Japan commanders of samurai combat teams used a gunsen, an instrument resembling a baton, which sometimes took the form of a folding fan. This instrument was an emblem of the rank of supreme commander of the army and was used to direct the movement of troops. Two heavy iron guards enclose the ten dark-colored bamboo ribs of this fan. Covered with lacquered paper, both ends of the ribs are glued to the iron guards. The lower ends of the ribs and guards are joined with a gilded copper alloy tube rivet. A design of the sun in red decorates the center of the fan. Simple and bold, this design would have been visible from some distance. Among other instruments used to direct the movements of large bodies of Japanese troops were gongs, drums, and conch horns." |

|

Tetsu |

鉄 てつ |

Iron: "...the Japanese themselves use the word “tetsu,” (“iron”) to refer to many of the various component parts and pieces of samurai armour that were fabricated from metal — mail and plate included. This, of course, is a recipe for disaster for foreigners who attempt to read, translate, and understand Japanese references to these items, because tetsu technically does correctly translate as “iron.” To the Japanese however, tetsu, particularly when used in relationship to items of samurai armour, does not necessarily mean “iron.” To them, when discussing armour, 'it is the generic term for “metal” and is automatically understood to mean either iron or steel, though neither is actually specified. For example, a “tetsu sabiji suji tate-bachi” properly translated into English is a “russet iron ribbed helmet bowl.” Though this translation is accurate, the use of the word “iron” again does not necessarily reflect the actual metallurgical properties of the piece being described." Quoted from: The Watanabe Art Musuem Samurai Armour CollectionVolume I ~ Kabuto & Mengu, Volume 1, by Trevor Absolon, p. 17. |

|

Tetsu kabuto |

鉄兜 てつかぶと |

Steel helmet

The image to the left is a suji-kabuto from the Muromachi period from the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. We found it at commons.wikimedia. |

|

The Theatrical World of Osaka Prints: A Collection of 18th & 19th Century Japanese Woodblock Prints in the Philadelphia Museum of Art |

|

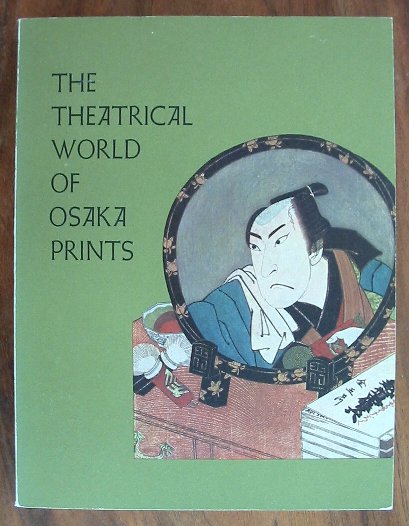

This is an excellent volume published in 1973. It was catalogued by Roger Keyes and Keiko Mizushima. While there isn't much color there is an extensive listing of artists, signature and actors and an informative text and should be on the shelf of any serious collector, student or scholar. 1, 2 |

|

Thunberg, Karl Peter |

カール.ペーター.トゥーンベリ |

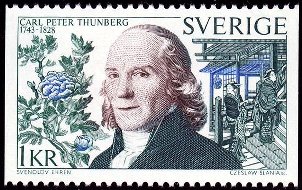

Swedish naturalist (1743-1828), pupil of Linnaeus, visited Japan from 1775-76. He was attached to the Dutch community at Deshima as a surgeon, but he did a lot of naturalist studies while there.

Hugo Munsterberg, in quoting James Michener, notes that Thunberg was one of the first Europeans to collect Japanese woodblock prints and to take them back to Europe with him. [See our entry on Titsingh below.] "He made a collection of ukiyo-e, including some excellent Harunobu and Koryūsai prints which are now in the National Museum, Stockholm." |

|

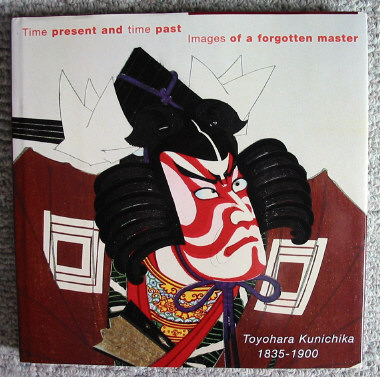

Time Present and Time Past: Images of a Forgotten Master: Toyoharu Kunichika 1835-1900 |

|

Not only is this the best book I know of on this late nineteenth century artist, but it also has three excellent appendices at the back. The first one is devoted to Kunichika signatures and seals, but the second and third are of more general interest to collectors and scholars of that period because the author gives large, clearly illustrated images of 19 publishers' seals and those of numerous carvers. Author: Amy Reigle Newland. Publisher: Hotei. Date: 1999. |

|

Titsingh, Isaac (or Isaak or Izaak) |

イザーク・ティチング |

1744?-1812 "Dutch trade commissioner in Nagasaki; diplomat. Born in Amsterdam. After training as a medical doctor he joined the Dutch East India Company and went in 1768 to its Asian headquarters at Batavia in Java. He was sent to Japan three times (1779-80, 1781-83, and 1784) to head the Dutch trading post at Dejima in Nagasaki. During his stay he made the acquaintance of Japanese scholars of Western learning and also made two official visits to the shogunate in Edo..." Quoted from: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 8, p. 30.

Of all of Titsingh's contributions to the field of Japanese-European studies the most important, at least for art historians, would be that he was credited by some as the first Westerner to return home with ukiyo-e prints. However, it might have been Thunberg who was the first. There were nine prints brought back to Europe by Titsingh, possibly including an Utamaro. "This small collection was known in Paris as early as 1806 and was sold there after Titsingh's death in 1812. Some of the prints eventually ended up in the collection of the French artist Bracquemond, who is usually credited with discovering Japanese prints." Quoted from: The Japanese Print: A Historical Guide by Hugo Munsterberg, p. 4.

To the left is a photograph of the tombstone of Titsingh at Pčre Lachaise Cemetary in Paris. It was posted at Wikipedia Commons by Pierre-Yves Beaudouin. One further note: We did try to find an image of Titsingh, but were unable to. There was one site that showed a beautiful painting of a man in a red coat, but it turns out that image was a portrait of General Cornwallis. This is why you should always check your sources no matter how definitive they seem. |

|

Tobiuo |

飛魚

とびうお |

Flying fish (Cypselurus agoo) - Tobiuo are among the fish represented in a series of prints by Hiroshige.

The image to the left was posted at Flickr by James Chou. The photo shown above was taken by Tim Wei and also posted at Flickr. |

|

Tōji |

杜氏

とうじ |

A saké brewer. "Tōji are the master brewers of the traditional saké kura, the elite of a unique breed of artisans who trace their roots to the Edo period. As the practice of kan-zukuri grew more prevalent, the saké-brewing season became increasingly concentrated in the coldest months of the year. Kura owners in areas like Nada--some of whom took an active interest in brewing but who were mostly wealthy merchants or land owners--came to rely on came to rely on outside groups of farmers or fishermen who were able to spend their unproductive months working away from home. These seasonal laborers were called the kurabito, "people of the kura," or the hyakunichi, "hundred dayers" (a reference to the shortened period of brewing). ¶ Among the kurabito was usually a leader from their home locality. Gradually there developed a complex and formal system in which these bosses, or tōji, played a central role, supervising all the details of the brewing and managing the work. The same tōji would work the same brewery each year. He in turn would pass his knowledge and rank on to his son, thus preserving the traditional art of saké making for generations. ¶ The origin of the term tōji is hotly debated among saké historians. The most convincing theory is proposed by an Edo-period dictionary, Wakun no Shiori, which traces the term back to the Heian period, when women played the most important roles in the Shinto rituals that accompanied the saké brewing of the court. The Engi Shiki (905) refers to these women as tōji, and the Wakun no Shiori suggests that male saké brewers adopted this term during the Muromachi period. Even today, tōji observe the Shinto rituals of brewing sake, and it seems highly likely that the brewmasters of the Edo period preserved this time-honored title for their rank in the hierarchy of the kurabito. By the early 19th century, tōji from particular regions had become associated with specific saké-producing areas. The most famous tōji were from Tamba and Tajima (modern Hyogo Prefecture), and traditionally worked in the breweries of Nada. The breweries of Fushimi near Kyoto were supervised by tōji from Echizen (modern Fukui Prefecture) and Tango (near Osaka). While these old pre-Meiji place names formally disappeared with the modern geopolitical reorganization of Japan, tōji still use them in referring to themselves and the traditions their sakes embody." Quoted from: Saké: A Drinker's Guide by Hiroshi Kondō, p. 37.

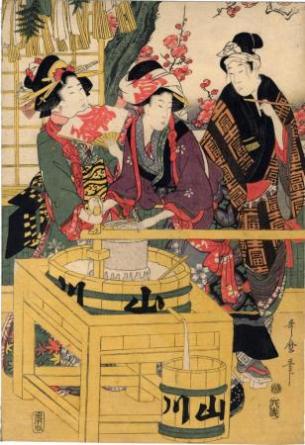

The image to the left is the left-hand panel of an Utamaro II triptych in the Lyon Collection. The fellow on the right has been identified as a tōji. His heavy coat indicates a cold time of the year, like winter. |

|

Tōkaidō |

東海道 とうかいどう |

Eastern Sea Road: "The Tōkaidō ran from Nihonbashi in Edo to Sanjō bridge in Kyoto. Traveling time between these two locations was reduced from 91 days in the period of Taika refomr (645) to 12-15 days by 1223, a speed that was maintained throughout the Edo period, with the exception of the much faster courier system. In 1604 the width was set to 5 ken. The Tōkaidō included fifty-five post-stations, and two more until its expansion to Osaka. Some of its stations were parts of castle-towns (jōkamachi), such as Odawara, Yoshida and Kuwana; temple-cities (monzen-machi) such as Mishima and Atsuta; and port-cities (minato-machi), such as Kawasaki, Shimada and Kanaya." (Quoted from: The Tōkaidō Road: Travelling and Representation in Edo and Meiji Japan by Jill Traganou, pp. 16-17) |

|

Tōkatsu jigoku |

等活地獄 とうかつじごく |

Hell of Revival -The hell of being torn to pieces and revived over and over. The first of the hot or burning hells. It gets its origin from the Sanskrit saṃjīva which means 'revival' or 'repetition.' "The exact punishment meted out on those unfortunate enough to be reborn in this hell varies depending on how the Sanskrit term saṃjīva is understood. First, saṃjīva may be interpreted as 'reanimation' or 'regeneration.' Thus, beings born into this realm are injured—in some versions by each other—in a variety of cruel ways, e.g., mangled, stabbed, pounded, and crushed. After meeting their demise so cruelly, they are then brought back to life and their bodies revived by a cool wind that sweeps over the entire realm; the same tortures are then repeated. Second, the term saṃjīva may be understood as 'repetition,' and beings in this hell are understood to undergo the sufferings they inflicted upon others." Quoted from: The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, p. 754.

"Hate is the main

characteristic of the Hell of Revival (tokatsu jigoku 等活 地獄, where sinners

wound each other with iron claws until nothing remains |

|

Toko |

独鈷

とこ |

Another term for the kongosho, i.e., the vajra, a symbol of esoteric Buddhism associated with the aspect of karma.

We found the toko to the left at Pinterest. The image shown above was posted at Wikimedia Commons by Takamina. |

|

At the beginning of chapter 5 of "The Tale of Genji" the young prince has been ailing with a persistent fever. He is told of "...a remarkable ascetic at a Temple in the Northern Hills..." who cured numerous people the previous year when everything else failed. Genji sent for him but the ascetic said he was too old to leave his cave. So, Genji went to him. After a short visit, as they are about to part, His Reverence "...gave Genji a single-pointed vajra, to protect him." (Source and quotes from: The Tale of Genji, translated by Royall Tyler, vol. 1, p. 92)

Tyler notes in footnote 34 that the vajra is also "...a symbol of supreme insight." |

||

|

|

||

|

Tokugawa Tsunayoshi |

徳川綱吉

とくがわつなよし |

The 5th Tokugawa shōgun, called the 'Dog Shōgun' (Inu kubō is 犬公方) - 1649-1709 - who ruled from 1680 to 1709. He was born in the Year of the Dog which helped perpetuate beliefs about him and his rule.

According to Beatrice Bodart-Bailey in her book The Dog Shogun: The Personality and Policies of Tokugawa Tsunayoshi differed from his predecessors in one particular way. They too had relied on the advice of Buddhist clergy, "But none of them had permitted Buddhist principles of nonviolence to infringe upon the samurai's traditional right to kill." (p. 130) The shogun's encouragement for love, peace and tolerance must have irked the samurai/warrior class beyond reason.

The image of Tsunayoshi to the left was posted at commons.wikimedia.org by Takanuka. The original painting is by Tosa Mitsuoki (土佐光起: 1617-91) and hangs in the Tokugawa Museum.

|

|

"Living in his Tatebayashi residence, Tsunayoshi had considerably less experience of the workings of government than did his predecessors. On the other hand, his understanding of social problems resulting from Japan's rapid urbanization would have been superior to that of any previous shogun. The Laws of Compassion well reflect the fact that Tsunayoshi clearly perceived the need to adapt communal values to changing social conditions but lacked the practical experience of how to induce his bureaucracy to assist him in bringing about this transformation. Paying little attention to the sanctity of tradition, he was explicit in condemning what he considered to be obsolete modes of behavior. He declared publicly, 'The old practices of the sengoku period became the way of the samurai and officials: brutality was regarded as valor, high spirits were considered good conduct, and there were many actions that were not benevolent and violated the fundamental principles of humanity.... ¶ Tsunayoshi demonstrated that these were not merely pious words by pro- mulgating unprecedented laws for the welfare of people at the bottom of the social scale. New provisions were made for the protection of minors. Previous rulers had already prohibited the abandonment of children, but now for the first time officials had to provide for their upkeep when parents were unable to do so. To counteract effectively the practice of infanticide, pregnant women and children under the age of seven had to be registered. Officials were ordered to provide beggars and outcasts with food and shelter. ¶ In an unprecedented fashion the shogun even turned his attention to the inmates of prisons; to improve their wretched state, he ordered the construction of better-ventilated buildings, provisions for five monthly baths, and addi- tional clothing during the cold months. Street gangs engaging in robbery and murder, a greater threat to the common people than to the well-armed samurai, were severely punished and effectively eliminated. Sick travelers, who in the past had commonly been turned out in the street when they could no longer afford their board or when their illness was deemed infectious, also now enjoyed the protection of the state. It was decreed that they must be provided with proper care and officials were responsible for the appropriate funeral arrangements in the case of death.... Barely four months after his succession in 1680 Tsunayoshi ordered that the practice of cutting horses' sinews, to make their gait more sprightly, should be discontinued. At the same time the traditional docking of horses' tails was abolished in the shogun's stables, and later an order was issued instructing his subordinates also to abstain from this practice." (pp. 168-169) |

||

|

|

||

|

Tokugawa Yoshimune |

徳川吉宗

とくがわ.よしむね |

The 8th Tokugawa shōgun ( 1684-1751: reigned 1716-45): "A forward-thinking Shōgun interested in Western science and technology. He actively encouraged the study of European developments through Dutch studies (rangaku), but this 'Dutch Mania' (ranpeki) lasted only as long as his thirty-year patronage." Quote from: Nakahama Manjirō's Hyōsen kiryaku, p. 115.

The shōgun "...permitted the import of western books of Dutch-language scientific works (so long as they contained no references to Christianity)." Quoted from: Interracial Intimacy in Japan: Western Men and Japanese Women, 1543-1900 by Gary Leupp, p. 84.

1719 was the year the shōgun partially rescinded the ban on European books. Most authorities give the date as 1720. Political and religious tracts remained on the proscribed list.

Yoshimune "...had his court mathematician, Genkei Nakane, consult prohibited works by Jesuits. The shogun was surprised to learn that Chinese calendrical astronomy had already made European calendrical astronomy part of its tradition. Since Chinese astronomy, the source of inspiration for the Japanese, had already moved in a Western direction, Japan would have to do the same. Yoshimune relaxed the book prohibition and directed that subordinates study European science." Quoted from: The Oxford Companion to the History of Modern Science, p. 209.

The image to the left is a detail from a painting posted at commons.wikimedia.org. |

|

In The Technological Transformation of Japan: From the Seventeenth to the Twenty-First Century (p. 24) it states that Yoshimune "...although as suspicious of the Europeans as any of his predecessors, recognised that the Dutchmen who came to conduct trade in Deshima possessed formidable skills of navigation and an extraordinary ability to predict the position of the stars in the sky. Yoshimune, who had an enquiring mind and an interest in the practical sciences, began to encourage the study of European astronomy, cartography, medicine and military science, and even ordered two of his samurai retainers to study Dutch so that they could learn from the Deshima traders. Official encouragement was short-lived, but 'Dutch learning' as the imported western sciences were called) acquired a dynamic of its own. The handful of scholars who had direct contact with the Dutch passed their knowledge on to disciples; the disciples in turn set up as teachers, often in the great cities of Osaka and Edo; and so the and so the small and uncertain trickle of western learning percolated slowly from one part of Japanese society to another."

"...a five-article ordinance was issued by the conservative, reforming Yoshimune during the winter months of 1722, setting the framework for all subsequent Tokugawa publication laws. The ordinance forbade 'excessively mendacious or heterodox discourses'; provided for the suppression of materials 'of an erotic nature deemed injurious to public mores'; called for 1rigorous investigation' of any books alleged to 'delve unfairly into the family lineages of other clans'; required colophons with authors' and publishers' names; and proscribed printed references to any Tokugawa family members. Although censorship was relaxed slightly in 1735, with permission granted to mention the shogun's name in certain cases, it was tightened again in the autocratic era of Matsudaira Sadanobu, under Shogun Ienari, particularly with a 1790 decree reiterating earlier restrictions and adding that it is 'forbidden to make baseless rumors into shahon (manuscript books) written in kana (phonetic script) or to lend such books out for a fee.' This decree added that since 'books had long been published, no more are necessary; so there ought to be no more new books.' Responsibility for enforcement of these regulations was to be borne, at least in part, by the booksellers and publishers guilds." Quoted from: Creating a Public: People and Press in Meiji Japan by James Huffman, pp. 16-17.

Yoshimune and the Kyōhō reforms (享保の改革): At a time of peace the old military class was losing its skills in the martial arts - "...Yoshimune, tried to reverse the trend during the Kyōhō reforms of the early eighteenth century. In good Confucian form, Yoshimune advocated uprightness in government and simplicity in personal habits, issued laws designed to curb sumptuous living and encourage ethical behavior, promoted administrative reform and the employment of men of talent, and encouraged agricultural production and fiscal responsibility. Yoshimune also tried to restore the martial spirit of a century before. As a martial artist himself, the shogun employed men skilled in the use of weapons, constructed facilities for weapon practice, and generally encouraged wider participation in the practice of various martial arts. ¶ Yoshimune was even interested in contemporary Western weapons and equestrian techniques. He requested the Dutch to demonstrate how to fire a gun from horseback; and in 1732 the bakufu received two suits of bulletproof armor that the shogun had been eager to see since 1723. Horses were of particular interest to Yoshimune for their military potential, and he had animals imported from Korea and China as well as the West, along with riding instructors from Holland. The study of Western equestrian techniques improved under such training, and in 1736 Imamura Danjūrō even compiled a work on Dutch horsemanship. ¶ But Yoshimune's attempt to breathe new life into the changing forms of martial arts ultimately failed because, in the end, the bakufu was a military government in an age of peace." Quoted from: Armed Martial Arts of Japan: Swordsmanship and Archery by G. Cameron Hurst III, pp. 80-81.

"The personal audience he [i.e., Yoshimune] granted the Dutch chief Joan Aouwer in 1717 lasted an unprecedented six hours. It was a clear indication to Japanese officials that the shogun was not willing to sever relations with the Dutch. Aouwer was invited to the innermost rooms of the shogunal palace where only Yoshimune's next-of-kin were admitted. Moreover, Aouwer was allowed to sit six paces away from the shogun which was as close as one could get to the ruler of Japan. ¶ The news of the exceptional audience spread like wildfire and in Nagasaki there was great relief, for the population was economically dependent on foreign trade." Quote from: The Furthest Goal: Engelbert Kaempfer's Encounter with Tokugawa Japan, pp. 55-6.

In the volume published by Henry Cabot Lodge in 1893, History of the Empire of Japan, it states: "Yoshimune had no sooner assumed administrative control than he set himself to restore financial order by closing or destroying several of the splendid mansions kept for the shogun's amusement, and dismissing their female and male inmates, while he himself sought to set an example to his people by wearing rough garments and faring in the simplest manner. Finally, he issued an edict urging the necessity of economy in all affairs both public and private, and as the nation had practical evidence of this spirit in the conduct of its rulers, not alone the ministers of state, but also the feudal barons adopting and following the admonition of the Shogun by the exercise of strict frugality, economy became one of the most marked features of the era. Yoshimune not only sought to foster this spirit of frugality, but also endeavored to promote industrial and agricultural enterprise. He encouraged the cultivation of Korean ginseng as well as Batavian and sweet potatoes ; he inaugurated the planting of Japanese sugar cane..." (pp. 324-25)

Yoshimune was "...the last great shogun; his successors tend to be figureheads manipulated by their ministers." Quoted from: Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture, p. 142.

This shogun standardized the penal code so that clerks and their superiors could no longer arbitrarily decide on what forms of punishment would be applied. Source: Punishment and Power in the Making of Modern Japan by Daniel Botsman, p. 16.

"Like flogging, tattooing was officially introduced by Yoshimune in 1720 to replace the older penalties of removing the nose and ears, and for this reason it is often pointed to as evidence of the alleviation of harsh punishments from the Warring States period. Yet, given that the use of these older forms of bodily mutilation had already declined dramatically over the course of the seventeenth century, it is, in fact, better understood as an attempt by the Bakufu (under Yoshimune) to reestablish its power to mark permanently the bodies of petty criminals. Though undoubtedly less painful and dramatic than slicing off a person's nose or ears, tattooing also had the advantage of allowing samurai officials to record additional information directly onto punished bodies. A person caught stealing for a second time, for example, would usually be tattooed with two lines across the forearm to mark them as a recidivist. A third offence would sometimes result in a third stripe. More often it meant death. The authorities in different areas of the country also used their own distinctive tattoos to make it easy to identify where a person had been punished in the past." Ibid., p. 27

Yoshimune established an herbal garden in Edo to be used for medical purposes. "Two of his decisions were of particular importance for European studies in the longer term. In 1720 he relaxed the ban on the import of 'Christian' books from China to the extent of admitting works on calendrical science prepared by the Jesuits in Peking. This was to recognize the superiority of western achievements in astronomy (though the Jesuits had not in fact accepted the Galilean description of the universe). Then in 1740 Yoshimune was persuaded by two of his advisers, one a physician, the other a Confucian scholar, that further scientific progress could not be made without a knowledge of Dutch, since this would give access to the relevant European literature. Both were ordered to pursue the study of it with the assistance of the Nagasaki interpreters. As a result, Dutch studies acquired a measure of respectability, becoming steadily more varied, more expert and more popular in the course of the next hundred years. ¶ It was not easy to make headway in the language without textbooks and works of reference. Oral instruction, often at Nagasaki, and the compilation of word-lists, soon proved inadequate for the study of serious topics. The first attempt to systematize the learning process was Ōtsuki Gentaku's guide to Dutch studies (Rangaku Kaitei), which appeared in 1788. It did not discuss grammar, but included sections on conversation, pronunciation, reading and writing, together with lists of words and sentences, showing Japanese equivalents. In the following year Ōtsuki opened a private school in Edo for the teaching of Dutch and western medicine. The first Dutch-Japanese dictionary of any importance was a cooperative undertaking, based on Francois Halma's Dutch-French dictionary of 1717, and was completed in Edo in 1796. A smaller, more convenient dictionary, having less than half as many entries, was published in 1810. The earliest grammars appeared at about the same time. ¶ Acquiring new kinds of knowledge required not only basic language skills, but also an ability to understand a technical terminology for which there existed no equivalent in Japanese. During 1770 Sugita Gempaku, a doctor who had already begun to study and practise western medicine in Edo, succeeded in obtaining — at a price which suggests suggests that the marketing of scientific books was a profitable sideline for members of the Deshima factory — a Dutch translation of a German set of anatomical tables, originally published by Johann Kulmus in 1722." Quoted from: Japan Encounters the Barbarian: Japanese Travellers in America and Europe by W. G. Beasley, pp. 23-24.

In the 1720s Yoshimune instituted the Kyōhō reforms (享保の改革).

Conrad Totman in his History of Japan (p. 273) wrote: "The next shogun of consequence, Yoshimune, was, arguably, the most energetic and imaginative of the dynasty, despite the severe neglect he has suffered in English-language studies. The diversity of his initiatives notwithstanding, however, nearly all his policies were in one way or another responses to the problems of resource scarcity, fiscal inadequacy, and their consequences. Indeed, he acquired the sobriquet kome shōgun, 'rice-shogun' because of his single-minded attention to such matters."

"After the brief reigns of two interim shoguns, Ienobu and Ietsugu, Tokugawa Yoshimune from the province of Kii was chosen as the eighth shogun in 1716. The great-grandson of Ieyasu, he was selected for his successful and rigorous reform in his own province. Enlightened but Confucian-oriented and conservative, he looked back to the age of the first shogun and tried to recoup the Tokugawa power. First of all, he promulgated extremely strict sumptuary laws and, unlike Tsunayoshi and the sixth shogun Ienobu, practiced thrift himself and encouraged martial arts. In an effort to save debt-ridden hatamoto knights and gokenin (lesser samurai in Edo who served the shogun directly), Yoshimune was willing to lend money even to lower-ranking samurai. In 1719 he categorically canceled the samurai's existing debts. This policy offered only temporary relief, however, for the official repudiation of debts made merchants distrustful of the samurai's credit standing and reluctant to lend any more." However, not all of Yoshimune's reforms were successful. His efforts to expand rice production had a number of negative effects and may even have contributed to the famine and starvation suffered in 1733 which in turn led to tax revolts. "Thus, although the Kyōho era (1716-1735) was extolled as the 'good old days' by later generations, in reality the era was not as golden and utopian as nostalgia made it appear." Source and quotes from: Yoshiwara: The Glittering World of the Japanese Courtesan by Cecilia Segawa Seigle, pp. 94-95

Nam Lin-Hur in the Prayer and Play in Late Tokugawa Japan: Asakusa Sensōji and Edo Society (p. 157) noted that there could be another downside to fiscal down-sizing: "For the bakufu, the view that construction and popular culture were important sources of income for the urban lower classes and that, therefore, sumptuary measures should be implemented with discretion did not arise from feelings of sympathy toward the urban poor. It was, rather, based on a painfully learned historical lesson. Because of a relatively high level of material consumption and public spending the bakufu was tempted to make construction projects, whether public or private, a prime target of its sumptuary fiscal policies. But a ban or restriction on construction had to be implemented cautiously, for unduly harsh belt-tightening measures that dried up jobs in the construction sector invited a much more serious problem: fire. When construction workers, day laborers, and lumber merchants were pressed too hard, Edo often suffered massive destruction and social turmoil because workers who had lost their jobs intentionally set fires in order to create new jobs for themselves. Fire was a final resort for unemployed laborers and the urban poor. After a disastrous fire, the bakufu usually had to subsidize reconstruction, which translated into new construction jobs. It is no wonder that soon after Shōgun Yoshimune launched the Kyōhō Reforms and enforced sumptuary measures on construction in the 1720s, Edo was hard hit by a spate of suspicious fires."

"The primary components of [Yoshimune's] reforms were increased diligence in land tax collection, sumptuary regulations and retrenchment directives for the samurai class, and attempts to expand government controls over commodity marketing and the activities of the mercantile sector of Tokugawa society." Quoted from: Change in Tokugawa Japan, p. 34. "Reforms initiated prior to 1722/5 varied from those implemented later in the Kyōhō period. Ōishi Shinsaburō has noted that those preceding 1722/5 were ad hoc efforts without any central concept to integrate them into a coordinated program, while those after 1722/5 were part of a coordinated program united in both theory and practice. The dividing point 1722/5 signifies a change in the advisors who were directing policy formation under the shogun Yoshimune. It is after this date that Yoshimune was able to begin his own programs without the interference of senior officials who tried to direct his efforts. It is this shift in direction which caused Ōishi to select 1722/5 as the beginning of the Kyōhō reforms under Yoshimune." Ibid., pp. 34-35

In 1722 Yoshimune's government imposed a direct tax on the daimyo. It was the first time they had been taxed directly. This was to stave off the starvation of some of the Tokugawa retainers. As a trade off the daimyo were told that they could halve the time they had to spend in Edo. This scheme lasted for 8 years until the government reverted to the previous arrangements. Quoted from: Tour of Duty: Samurai, Military Service in Edo, and the Culture of Early Modern Japan by Constantine Vaporis, p. 14. It was important to weaken the daimyo, but to still keep them solvent. Ibid., p. 56

One of Yoshimune's attempts to control wasteful spending was to stop the practice of putting six copper coins inside the coffin of a deceased relative. Source: Asian Material Culture, essay by Martha Chaiklin, p. 51. |

||

|

|

||

|

Tokugawa Yoshinobu |

徳川慶喜

とくがわよしのぶ |

The last Tokugawa shōgun - born in 1837, died in 1913. Yoshinobu became the 15th shogun on January 10, 1867.

Many sources give the dates of Yoshinobu's shogunate as 1866-68, but James L. McLain in his Japan, A Modern History explains why the dates are actually 1867-8. "Japan's lunar-based years were not exactly cotermonous with their Western counterparts, however, and dates falling in the final two months of a Japanese year might find their equivalent in the following Western year. Since Tokugawa Yoshinobu, the last member of his family to hold the position of shogun, took office on the fifth day of the Twelfth month of Keio 2, for instance, his date of appointment often is given as 1866, whereas the exact correspondence is January 10, 1867."

To avoid a full-blown civil war he handed political power over to the emperor November 9, 1867. Ten days later he resigned as shogun. Wary opponents of Yoshinobu seized his palace in early 1868 and on January 3 an edict deprived him of any powers he still had. "The text made it clear that responsibility for governing the country was to revert to the emperor. It was this which has given the event its English-language name: the Meiji Restoration, that is, the restoration to the young Meiji emperor (Mutsuhito), who had succeeded his father Komei earlier in the year, of the administrative authority which heads of the Tokugawa house had for several centuries exercised. ¶ The coup d'etat did not immediately settle all the arguments. Yoshinobu withdrew to Osaka." Would he be granted a seat of power within the government and would he be allowed to keep his lands? Supporters tried to enforce this demand, but lost and the former shogun was forced to flee to Edo. The new government declared him a rebel. Weeks later, as an imperial force 'marched' toward Edo Yoshinobu gave orders to his men not to resist. Edo was occupied in early April and Yoshinobu was forced into retirement at Shizuoka where he was allowed to keep lands of 700,000 koku. (Source and quotes from: The Rise of Modern Japan by William G. Beasley)

Yoshinobu is buried at Tenno-ji in Tokyo, but there is no public access to his grave. (Source: Top 10 Tokyo)

The name Yoshinobu can also be read as Keiki and often is. He is also known as Hitosubashi Keiki. Marius Jansen in The Making of Modern Japan says that Yoshinobu was "...able and highly regarded." He had been a candidate for shogun earlier, but failed to gain that position. However, he was named Guardian for the new young shogun Iemochi (1846-66). |

|

According to Classical Weaponry of Japan by Serge Mol Yoshinobu was an enthusiastic student of the shuriken (手裏剣) or hand-held throwing blade. Although there are many types of shuriken the shogun is said to have been most interested in the straight nail or spike-like forms. Below are some bo shuriken from a posting at commons.wikimedia.

John Black, an Australian journalist in Yokohama, gave a generous appraisal of Yoshinobu and 'what if': "He initiated many reforms for which the present government obtains the credit ; and whatever advantages there may be — and undoubtedly there are many — in having the Government in its present shape—he had foreseen them, and declared his hope of gradually bringing it about. It is my sincere belief that, had he been permitted to work in his own way, we should have seen Japan make as rapid progress as she had made, without all the horrors of revolution, and repeated outbreaks of internal strife, that have occured." Quoted from: The Image of Japan: From Feudal Isolation to World Power 1850-1905 by Jean-Pierre Lehmann.

The entry on Yoshinobu in the 1922 Encyclopedia Britannica noted that when he became shogun that "At that time already a man of matured intellect and high capacities, although his succession had been obtained by the conservatives, he soon displayed an advocacy of liberal progress." The emperor gave Yoshinobu the title of prince as a reward for his resignation and said the title could be handed down to the ex-shogun's heir.