|

JAPANESE PRINTS A MILLION QUESTIONS TWO MILLION MYSTERIES |

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

|

Kansas City, Missouri |

|

INDEX/GLOSSARY

Awase thru Bl |

|

|

|

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

Awase, Ayame, Ayatsuri, Azana, Azusa, Badarai, Merrily Baird, Bakemono, Bakin, Bamboo (Take), Bamboo & Sparrows (Takesuzume), Bandō Hikosaburō III, Bandō Mitsugorō v, Bandō Mitsugorō III, Bandō Shūka I, Bangasa, Banjaku, Bansho wage goyō, Banzuke, Baren, Baren, Baren-sujizuri, Bashi, Bat motif, Batō, Batō-Kannon, Bekkō, Bengara, Benibana, Beni-e, Benigirai, Benkan, Ben(zai)ten, Bero-ai, Bijin, Bira bira kanzashi, Bishamon, Bishamonkikkō Biwa hōshi and Blue & white porcelain

袷, 菖蒲, 操人形, 字, 梓, 馬盥, 化物, 馬琴 竹, 竹雀, 三世坂東彦三郎,五世坂東彦三郎, 坂東三津五郎, 坂東しうか, 番傘, 盤石 or 磐石, 蕃書和解御用, 番付, 馬連, 馬簾, 馬士, 馬頭, 馬頭観音, 鼈甲, 弁柄, 紅花, 紅絵, 紅嫌い, 冕冠, 弁(財)天, ベロ藍, 美人, びらびら簪 毘沙門, 毘沙門亀甲and 琵琶法師 |

|

|

|

One more note about this page and all of the others on this site: If two or more sources are cited they may be completely contradictory. I have made no attempt to referee these differences, but have simply repeated them for your edification or use. Quote anything you find here at your own risk and with a whole lot of salt. |

|

|

TERM/NAME |

KANJI/KANA |

DESCRIPTION/ DEFINITION/ CATEGORY Click on the yellow numbers to go to linked pages. |

|

Awase |

袷

あわせ |

An awase is a lined, winter kimono. Its counterpart is the hitoe or unlined, summer kimono.

Traditionally four times a year the Japanese celebrated the seasonal changes by a formal change of clothes. For example, Spring officially ended with the Boy's Festival on the fifth day of the fifth month and Summer began on the sixth day. These changes were referred to as koromogae (衣替え). "The seasonal change of dress was strictly observed by the Imperial Court since very early days, under fixed rules." During the Tokugawa era the government followed suit. "...people wore katabira [帷子] or summer unlined dress from May 5; awase or lined dress from September 1; wataire [綿入れ] or cotton stuffed dress from September 9, and again awase from April 1, the next year." (Source and quotes: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, p. 29)

On left is a modern awase komon posted by Pitke at commons.wikimedia.org/.

Liza Dalby in her book Geisha says: "From September through April, women should wear kimono of the lined type called awase. Commonly, this kimono will be a weighted silk crepe de chine garment with a lining of lighter crepe or silk mousse-line." Later she adds: "Awase kimono are worn eight months out of the year, so a woman's wardrobe will have more of these than the unlined hitoe kimono, which is worn only in May and possibly June, or the light silk leno-weave ro kimono June through August. A good summer ro kimono might cost more than an ordinary awase, but a very good awase kimono will be the most expensive kind of kimono there is." Dalby notes that the word awase comes from the verb awaseru, "to put together". |

|

|

||

|

Ayame |

菖蒲

あやめ |

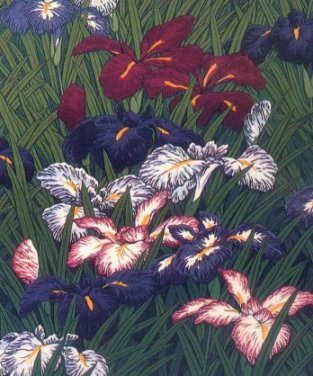

There are quite a few different terms describing iris plants and their flowers. Ayame refers to either the iris flower or the Siberian iris (Iris sanguinea).

The detail to the left is from a Hasui print.

This photo was provided by Shu Suehiro at Botanic.jp.

There are three different groups of irises in Japan: ayame, kakitsubata and hana-shobu. The ayame prefers a drier environment. Mostly these flowers are purple, but white ones can be found too.

The hana-shobu (花菖蒲) or Japanese water iris is an Iris ensata. From what we know of this type of iris the image by Hasui to the left looks more like the hana-shobu than the ayame.

There is an expression "izure ayame ka kakitsubata" (いずれあやめかかきつばた) which basically means the ayame and kakitsubata are equally beautiful, but is actually a way of referring to two equally beautiful girls.

|

|

Ayatsuri |

操人形 あやつり |

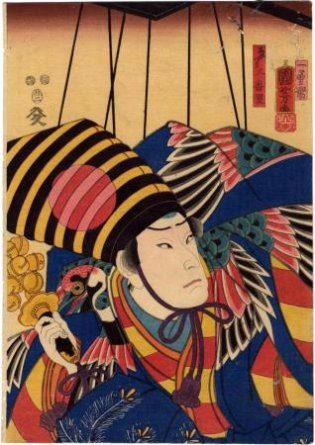

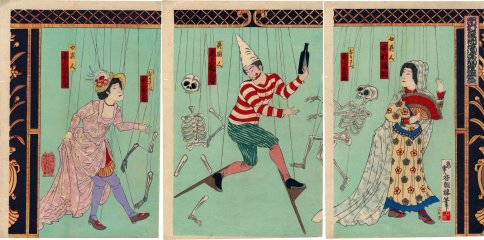

Marionettes or puppets - "AYATSURI (marionette plays now shown in Japan are mostly of the European type which were introduced about 60 years ago. But ayatsuri shows first appeared in the country in the Kanbun era, 1661-1673, in Kyoto and Osaka, probably imitating the Chinese type of marionette. ¶ Ayatsuri is quite different from Bunraku puppet shows which appeared about a century later, and in which dolls are manipulated by hand. Ayatsuri dolls are controlled by strings, and as they are small, the show was commonly called Nankin ayatsuri, meaning small doll plays. ¶ In the Genroku period, 1688-1704, as the shows became popular ayatsuri theaters appeared in Kyoto, Edo and other cities. Good plays were written for ayatsuri, and many expert manipulators developed. ¶ Some of the ayatsuri plays were grotesque. In one play, a warrior was killed by his enemy and cut into small pieces. Crows carried away the pieces. But the dead man's brother arriving there, prayed for the return of the warrior. Suddenly pieces of the dead man fell on the ground and joined to form a whole body, and then revived. The hunting of tigers and other wild beasts was also a popular theme for ayatsuri. ¶ Because of the popularity, toy ayatsuri dolls were sold for children. ¶ Ayatsuri was popular until the middle of the Meiji era. With the introduction of the Western marionette technique, a new school mostly giving comic plays, was started..." Quoted from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, pp. 457-8.

Above is a triptych from 1893 by Kōchōrō from the Lyon Collection. Click on the image to learn more about it. To the left is another print in the same collection. This one is by Kuniyoshi. Click on it for more info. |

|

Azana |

字 あざな |

A pseudonym, an alias or a nickname. While azana does not refer specifically to Japanese artists, we came to it from our studies of those elements of their societies.

"The azana, translated "nickname" for want of a better equivalent.... Chinese scholars specially affect these, which are not vulgar, like our nicknames, but on the contrary, highly elegant." Quoted from: Things Japanese: Being Notes on Various Subjects Connected with Japan for the Use of Travellers and Others by Basil Hall Chamberlain, p. 346. |

|

Azusa |

梓

あずさ

|

All of the images of the catalpa tree shown here are provided courtesy of Shu Suehiro at http://www.botanic.jp/plants-aa/amekis.htm.

Catalpa tree: A bow made from a catalpa was traditionally used to drive away evil spirits or in the case of shamans such as miko to draw them out and make them reveal themselves. "The catalpa bow with the hempen string is now less often seen in the north than its variants, the ichigenkin or one-stringed lute. In the past, however, it was clearly in widespread use. The literature of the Edo period contains many references to miko who, tapping the string of their catalpa bow with a bamboo rod, deliver a terrifying lament from a ghost in hell. That the use of this bow as a summoner of spirits is ancient is testified by the use of the word for catalpa bow, azusayumi, in the great eighth century anthology of poetry Manyōshū. Here it appears many times as the... epithet of the word yoru. Yoru is a verb meaning either 'to approach' or 'to possess'. From the close association between the two words we infer that when the bow gives forth its sound, spirits are compelled to approach and possess the waiting medium [or miko]. Both the bow and the one-stringed lute are probably simpler forebears of the koto, which we saw at the time of the Empress Jingo already to be the instrument used to summon deities." (Quoted from: The Catalpa Bow: A Study of Shamanistic Practices in Japan by Carmen Blacker, p. 148)

Catalpa bow diviners are referred to as azusa miko in Of Heretics and Martyrs in Meiji Japan by James Ketelaar, p. 51. |

|

Badarai |

馬盥 バだらい |

Trough or basin used in washing horses - Below is a detail from an 1825 Kunisada triptych at the British Museum. It shows a horse's bit in the water.

|

|

Baird, Merrily |

|

|

|

Bakemono |

化物 ばけもの |

Goblin, ghost, monster - Synonymous with yōkai.

"The Tokugawa-period word that best approximates the broad meanings of yōkai was bakemono, which can be translated literally as 'changing thing.' This emphasis on transformation denotes powers traditionally attributed to such creatures as foxes, for example, which could take on different forms at will. The word bakemono, however, was not limited to shape-shifting things; it also signified a wide range of strangely formed, anomalous, or supernatural creatures. Although explicit shape- shifting abilities may not have been intrinsic to many things that were called bakemono and later yōkai, the notion of mutability provides an important key to the ontology of the mysterious." Quoted from: Pandemonium and Parade: Japanese Monsters and the Culture of Yokai by Michael Dylan Foster, pp. 5-6.

Foster notes that there were stories of shape-shifting going back to the Heian period (ca. 794-1185) before the terms bakemono and yōkai were used. |

|

Bakin |

馬琴

ばきん |

First I want to make something absolutely clear in hopes that this will assist future researchers who dabble at Japanese culture as I do: I have decided to put this entry under this author's popular name as opposed to any other family or acquired name. Why? Because no matter what book you look in chances are the index will reference him under any one of a number of possible listings - and not necessarily one beginning with the letter 'B'. This can be extremely confusing for beginner and might even prevent them from finding the information they are seeking. People should always look under each of the variations until they find what they want before moving on. For example, Bakin can be found under 'B" in the Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, under 'K' for Kyokutei in The Princeton Companion to Classical Japanese Literature and under "T" for Takizawa in Donald Keene's World Within Walls: Japanese Literature of the Pre-Modern Era 1600-1867. Chances are if I kept digging I might find other examples, but I feel confident that these three probably represent 95% plus of what there is to be found. That said... |

|

Aston wrote in a History of Japanese Literature (p. 352) at the turn of the 20th century: "One of the few Japanese authors whose fame has penetrated to Europe is KIOKUTEI BAKIN (1767-1848). In his own country he has no rival. Nine out of ten Japanese if asked to name their greatest novelist would immediately reply 'Bakin.' Born in Edo the third son of a shogunal retainer he was a restless youth. For a while he was assigned to attend the son of his father's master. Later he studied with a physician and then with a Japanese scholar of Chinese. Bakin failed to finish his studies with either of these. For a time he was a fortune teller in Kanagawa near Yokohama, that is, until he lost everything in a flood. [Not a very good fortune teller, eh?] Destitute he returned to Edo where he met the novelist Santō Kyōden (山東京伝) who took him into his own household. ¶Bakin published his first novel in 1791 in which he said he credited Kyōden as his master. Kyōden was so impressed with Bakin's work that he said "In twenty or thirty years I shall be forgotten." [Verrocchio, Leonardo's teacher, supposedly gave up painting and stuck to sculpture after seeing he work of his young apprentice. Vasari [ ヴァザーリ] in his Lives of the Painters even said that Verrocchio was angry that Leonardo was so much better than he was.] ¶With Kyōden's help Bakin got a job as an assistant to a bookseller. While there he published another novel - this one illustrated by Hokusai "...was very successful." (Ibid., p. 353) Bakin was said to be a strapping fellow and was asked to join a group of wrestlers visiting the bookseller. The young author declined. His boss's uncle, the owner of a teahouse whish had connections with a brothel next door, wanted Bakin to marry his attractive daughter. According to Aston "Bakin refused disdainfully to become connected with a family which drew its income from this source. Brothel-keeping, he said, was no better than begging or thieving, and he must decline to disgrace the body he had received from his parents by such a marriage." [Very Confucian of him. This is interesting on another level too: Kyōden was no stranger to the pleasure districts. As a young man he published prints of courtesans, may have married two women who worked for brothels and published at least 15 novels which dealt with that subject. Is it any wonder that he and Bakin became arch-rivals?] ¶Instead of marrying into a family with connections to prostitution Bakin married the daughter of a wealthy widow of a shoe dealer and was adopted into as her heir into their family. (Ibid.) When Bakin's daughter was old enough to wed he handed over the business to his new son-in-law freeing himself for more time for writing. When he started going blind in his seventies he hired his son's widow "...as his amanuensis." (Ibid., p. 354)

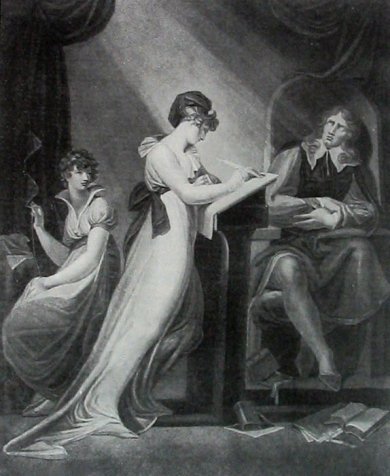

Like Bakin who dictated to his daughter-in-law after he went blind Milton (ミルトン) dictated to his daughters. This is from a print after Fuseli (フューズリ).

"He died at the age of eighty-one, after a career as an author of more than sixty years. The amount of saleable 'copy' produced by Bakin can have few equals in literary annals. His pen was never at rest, and the rapidity with which he composed may be inferred from the circumstances related by himself, that one of his novels (of about two hundred pages) was completed by him in a fortnight, to stay 'the demands of an importunate publisher." He is said to have written no fewer than two hundred and ninety distinct works, many of which were extremely voluminous. Some authorities put the figure still higher." (Ibid.)

Aston noted that "Bakin was not an amiable man. He is described as upright, but obstinate and unsociable. A single word which offended him made of him an enemy for life. Even Kiōden, to whom he owed so much, could not get on with him. The famous artist Hokusai, who illustrated many of his novels, had also reason to complain of his morose and intractable temper. Edmond de Goncourt, in his life of Hokusai, says that the quarrel between the painter and Bakin occurred in 1808, and was caused by the immense success of the illustrations to the Nanka no yume, of which Bakin was jealous. It was smoothed over by friends, but broke out again with great violence in 1811, when a continuation of that novel was brought out. Bakin accused Hokusai of paying no attention to his text, and demanded that the drawings should be altered. But the publishers had already engraved both text and pictures." Aston goes on to point out that this may have been the impetus for Hokusai publishing his own work without literary collaborations. [A better explanation for their tensions may be due to fact that both of them may possibly have been prima donnas. What do you think?]

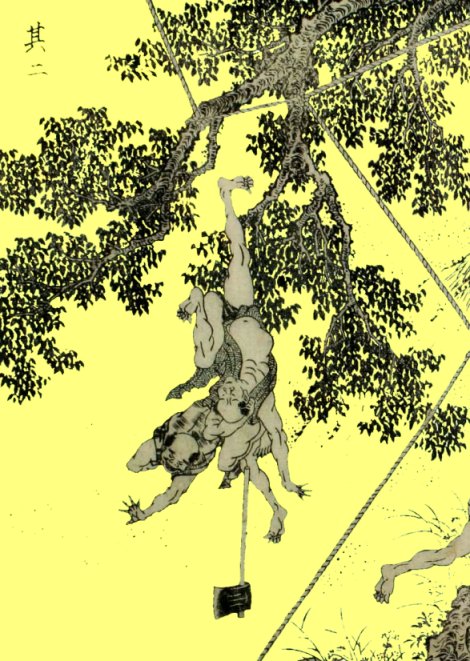

Above is an adulterated illustration by Hokusai to Bakin's Nanka no yume.

Aston says that many people consider his Yumibari-tsuke (弓張月) from 1805 his masterpiece. "It professes to be an imitation of the Chinese romantic histories, but departs far more widely from historical truth, and is indeed a romance pure and simple, though a few of the personages have names taken from real history." Over 800 pages are devoted to the story of Hachirō Tametomo, a 12th century hero of Japanese lore. (Ibid., p. 355) ¶ In 1806 Bakin came out with his adaptation of the Chinese classic Journey to the West. In Japanese it is called Seiyuki (西遊記). [There is much to say about this great novel, but for now we have little to offer. Eventually we hope to add much more. For an incidental bit of information see our entry on jinmenju or the human-faced tree.] "He also translated the Shui-hsü-ch'uan (Sui-ko-den in Japanese)... The influence of these and other Chinese romances is very noticeable in the works of Bakin and his school." (Aston, p. 359) ¶ "The most famous of Japanese novels is the enormous work entitled Hakkenden [八犬伝]. Begun in 1814, it was not finished until 1841. In its original form it consisted of one hundred and six volumes, and even in the modern reprint [remember this is being written in 1907 or a little earlier] it forms four thick volumes of nearly three thousand pages." Aston was astounded by the Hakkenden's popularity when he found it so pedantic and tedious. Nevertheless, he said "The wood-engravers came daily for copy , and as soon as a part was ready it was printed off in an edition of ten thousand copies, creating a demand for paper which, we are told, appreciably affected the market-price of that commodity." (Ibid., pp. 360-1) |

||

|

|

||

|

Bamboo (Take) |

竹

たけ |

One of the "Four Gentlemen" or Shikunshi which are flowers which mirror positive human traits. The other three are plum, orchid and chrysanthemum. Borrowed from the Chinese and linked to Confucian concepts. 1 |

|

Bamboo & Sparrows (Takesuzume) |

竹雀

たけすずめ |

"The association of the sparrow (suzume) with both bamboo and rice heads is an old one found in Japanese poetry, painting and design. The bird is said to be obsessed with its honor..." Quoted from Symbols of Japan... by Merrily Baird, pp. 118-119. |

|

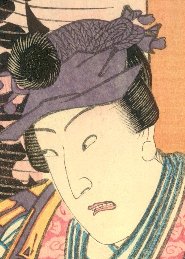

Bandō Hikosaburō III |

三世坂東彦三郎

ばんどう.ひこさぶろう |

Kabuki actor (1751-1828). 1 |

|

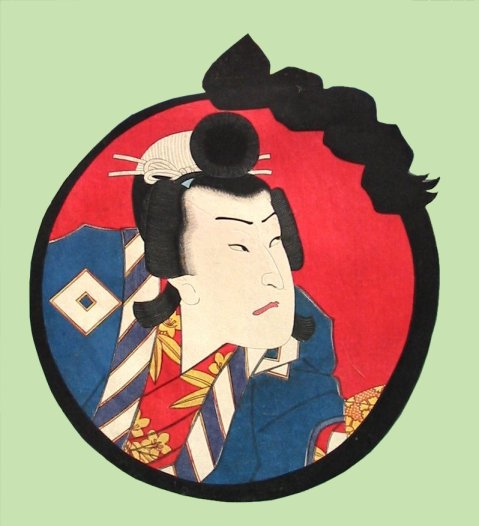

Bandō Hikosaburō V |

五世坂東彦三郎

ばんどう.ひこさぶろう

|

Kabuki actor (1833-77). He took this stage name in 1856. Extremely popular and versatile. Able to play a wide range of roles. 1, 2, 3, 4 |

|

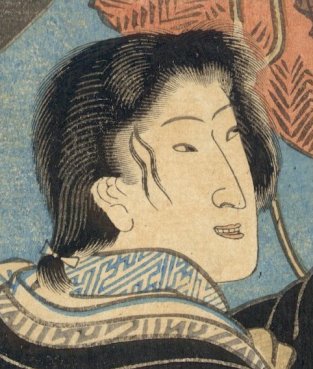

Bandō Mitsugorō III |

坂東三津五郎

ばんどう.みつごろう |

Kabuki actor (1773-1831). He received the name Mitsugorō in 1799. 1 |

|

Bandō Shūka I |

坂東しうか

ばんどう.しうか |

Kabuki actor (1812-1855). He took this stage name in 1832. The 'Shūka" part is spelled only in kana characters. Posthumously he was named Bandō Mitsugorō V. One of the two most popular Edo actors in the 1840s & 1850s. |

|

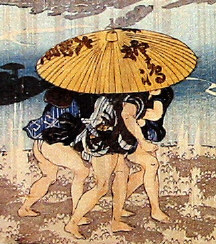

Bangasa |

番傘

ばんがさ |

A crude umbrella made with oiled paper which often carried advertising for a shop or other business. "The syllable ban (number) in the word bangasa derives from the fact that these cheap umbrellas were often numbered by rental shops for purposes of identitfication." Quote from Julia Meech's entry in Rain and Snow: The Umbrella in Japanese Art, cat. entry #17. |

|

Banjaku |

盤石 or 磐石

ばんじゃく |

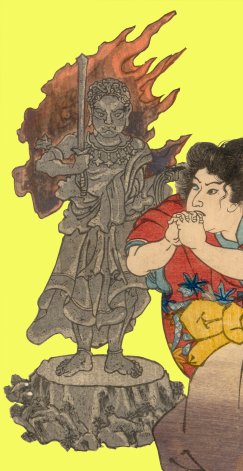

Banjaku translates as a 'huge rock' or 'firmness'. They are the 'seat' or 'throne' upon which the 'lions of Buddha' are placed. Often Fudō Myōō stands or is seated on a banjaku. The fact that Fudō, who is referred to as adamantine, stands upon a base which is called 'firmness' can be no accident.

In the Dictionnaire Historique du Japon in an entry on Fudō Myōō it states in the 2002 edition, pp. 575-6: Il siège sur in rocher (banjaku 磐石, shitsushitsuza 瑟瑟座, śilā) image du Mont Sumeru (Shumisen 須弥山), qui est au centre de l'universe selon la cosmogonie indienne: c'est la montagne par excellence, dont le caractère essentiel est l'immobalité (acala signifie souvent montagne en sanskrit) et qui, dans le symbolisme bouddhique, représente le caractère immuable du Nirvāna. Ce rocher prend la forme du bûcher dressé pour le rite de réalisation mystique par le feu (gomahō... homa-viddhi), tel que le décrivent les textes rituels du Shugendō 修験道. On remarquera également que les roches sacrées (iwakura 岩倉 ou 磐座) sont souvent des lieux de cult du Fudō."

Image to the left is an altered image by Kuniyoshi showing Fudō standing on his banjaku. |

|

Bansho wage goyō |

蕃書和解御用 ばんしょわげごよう |

Bureau for the Translation of Barbarian Texts |

|

"The only Japanese even remotely capable of assembling and assessing information from foreign sources were the Nagasaki interpreters and rangaku scholars studying various aspects of Western science and medicine. By the nineteenth century, the isolation the bakufu had imposed on Japan two centuries earlier had made it completely dependent upon the few Japanese who could speak or read Dutch, and even the most avid and talented scholars were severely limited in their ability to learn about the state of world affairs. ¶ To address this weakness, in 1808 the bakufu established a Bureau for the Translation of Western Books (Bansho wage goyō) at the Tokugawa Astronomy Observatory (Tenmondai) in Edo's Asakusa district. The bakufu appointed the Edo physician, Ōtsuki Gentaku, the acknowledged founder of the rangaku movement, as Director of the Translation Bureau. Gentaku then chose prominent Dutch scholars, the majority of whom were physicians, to work under him. In addition to the physicians, the translation team included some astronomers, botanists, and Dutch interpreters. In essence, the Bansho wage goyō was a Tokugawa in-house research team: its task was to translate Western books on subjects considered of interest and importance to the Tokugawa government. However, given the government's ignorance about foreign matters, the tenmonkata as those who worked at the Tenmondai were called, were pretty much on their own to decide which books, among those available to them, should be translated into Japanese. ¶ One consequence of the creation of Translation Bureau at the Tenmondai was that it brought Japan's rangaku scholars under the surveillance of the Tokugawa government for the first time. Clearly this was the bakufu's intention. It was no longer appropriate to have Japan's most capable translators situated far from the seat of government in Nagasaki, interacting with Dutch merchants who now were staying for long periods and becoming much more familiar with Japan. Of even greater importance in the longer term, perhaps, the creation of a Translation Bureau in Edo institutionalized the work of the rangaku scholars within the bakufu. Setting Japanese scholars at work on joint projects allowed them to share information and to develop positions and attitudes that might be at odds with bakufu policy. The Tenmondai and the Translation Bureau were beginning to take up the functions of a university, and the tenmonkata were acting like colleagues." Quoted from: The Vaccinators: Smallpox, Medical Knowledge, and the 'Opening' of Japan by Ann Bowman Janetta, pp. 67-68.

William Deal and nearly all other scholars say the Bureau was established in 1811. This is also the date given by the National Diet Library.

"In this changing situation there occurred a shift of emphasis in Japanese studies of the outside world. In 1811 the Bakufu established its own translation office within the astronomy bureau, putting it under the supervision of two well-known Rangaku scholars. For the next twenty years the staff of the office devoted itself in large part to translating a Dutch version of a French encyclopaedia of 1778-86, which furnished information on a wide variety of 'useful' subjects (not least the secret of attaining a happy old age). It was the kind of book, in fact, which can in many ways be compared with those the Japanese had used in order to gain a knowledge of China in the seventh and eighth centuries; but although many items from it were summarized or translated, especially on medicine, botany and zoology, nothing had actually been published by 1846, when the project was abandoned. ¶ Meanwhile at Nagasaki the range of Japan's linguistic studies had been increased. One of the castaways brought back by Laxman had acquired enough Russian to start teaching the language; Rezanov's visit in 1804 had prompted the teaching of French (by the Dutch at Deshima, initially), since it was used in the documents the Russians brought; and the Phaeton affair led to the study of English in 1809." Quoted from: Japan Encounters the Barbarian: Japanese Travellers in America and Europe by Wiliam Beaseley, 1995, page 30. |

||

|

|

||

|

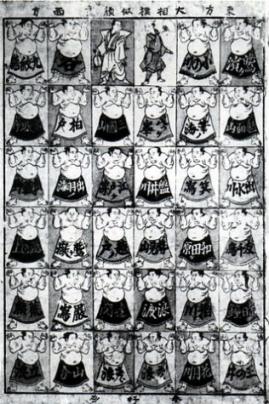

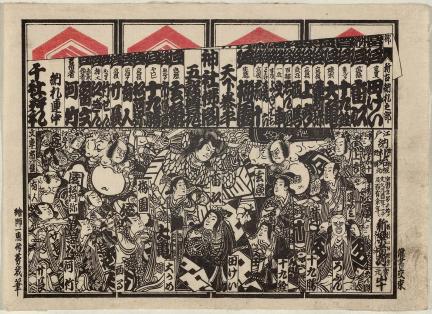

Banzuke |

番付

ばんづけ |

Banzuke has been defined as a list, a ranking, a program, etc. Samuel Leiter in his Historical Dictionary of Japanese Traditional Theatre (pp. 41-42) lists a number of different types including kaomise banzuke, tsuji banzuke, mon banzuke, ehon banzuke, et al. Leiter writes: "The woodblock print bunraku and kabuki 'programs' of the Edo period. They provided the play's title, performers, and character list, as well as illustrations of the play or performers. In bunraku, the relative thickness of the Chinese characters and their placement on the program indicated the rank and quality of the performers. This practice came into use in the early 17th century and was not abandoned until 1957." It was reinstated in 1984. Later Leiter notes: "While the English word 'program' is used elsewhere in Japan, the Kamigata area still uses banzuke."

The image to the left was found at Wikimedia.commons. It is said to be from 1788 and represents a style called sumo banzuke. |

|

"The word banzuke covers a wide range of printed publications from programmes and playbills to guide books, some illustrated, others plain text. What has become recognised as the banzuke format grew out of the Edoite's love of grouping and ranking. Originally produced to list or rank actors and sumo wrestlers, banzuke turned into a popular formula. Creating 'best ten, best hundred' lists was a popular Edo parlour game and is a journalistic ruse still used today. Enjoyment lay in the enumeration and marshalling of quantities of information and the banter involved in arranging it all in order. This activity has a long history in Japan, one of the earliest examples being the late 10th century author Sei Shonagon who made lists of hateful things, elegant things, etc. Although the Edo activity was playful in spirit, banzuke rankings did have a practical application, especially in the three important entertainment worlds of Yoshiwara, kabuki and sumo. The sophisticated connoisseur had, above all else, to be in the know, and these highly visual prints were packed with information."

Yoshiiku 1861 banzuke Museum of Fine Arts, Boston |

||

|

|

||

|

Baren |

馬連

ばれん |

This is the most important tool used in woodblock printmaking. The printer rubs the back of a sheet of paper which has been laid down over an inked block.

Hiroshi Yoshida in his Japanese Wood-block Printing (p. 55) describes the origins of the baren: "Now let us consider the tools used in printing. The first in importance is the baren. The term now consists of two characters: ba meaning sheath (sheath of bamboo) and ren, succession. These may not be the original characters used. The term may be foreign to the soil. In Manchoukuo a kind of iris is known as ma-ren, and ma is often blurred into ba in Japanese. This plant may have been originally used in making this implement which has so acquired its name. The origin of the baren is not clear. Perhaps it was introduced into Japan by the Chinese who came over to Japan and cut Buddhist sutras on wooden blocks and printed from them in the Muromachi Period (1334-1572). But no mention of it is made in literature." Yoshida continued to say: "The baren is the soul of the printer. All the secret of print-making may be said to be contained in this circular pad used for rubbing in printing." [We find Yoshida's comment curious: "The term now consists of two characters: ba meaning sheath (sheath of bamboo) and ren, succession." We are not versed enough in our understanding of the Japanese language, but the first kanji character is 馬 which, inexplicably, means 'horse'.]

Ellis Tinois wrote: "In the Edo period printers made their own baren. It consists of three parts: a backing made of a laminate of thirty to forty sheets of paper covered with lacquered silk; a core made of twisted fibres tightly braided and then coiled into a flat disc; and a wrapping of prepared bamboo leaf that provides the smooth printing surface, holds the backing and the core together and, on the top side of the baren, is folded and twisted in such a way as to form the handle. When properly cared for, the core and backing last indefinately; the bamboo-leaf covering has to be changed at regular intervals."

|

|

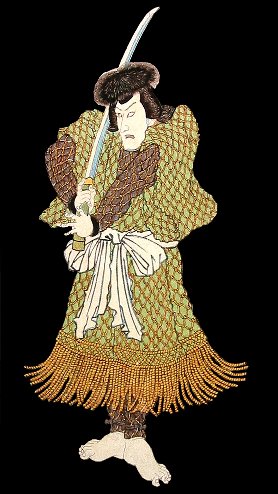

Baren |

馬簾

ばれん |

"The decorative gold or silver (sometimes, red and white) fringe, normally six inches long, attached to the lower hem of yoten costumes worn by samurai in jidaimono. It is also worn by sumo wrestlers on their ornamental aprons." A yoten is an outer kimono hiked up to the calves.

The image to the left is taken from a Kuniyoshi print. Clearly the fringe here is black. Above is a figure taken from a print by Toyokuni III. |

|

Baren-sujizuri |

|

Baren-sujizuri is the term which describes one of my favorite effects on Japanese prints. Not obvious on all of them occasionally these markings are made more pronounced as in the examples seen to the left. Here one can clearly see the touch points of the baren as it was applied in a circular motion to the back of the sheet lying against an inked board. The print is by Torii Kotondo (1900-76 鳥居言人).

These examples were sent to me by my good friend M.

Hiroshi Yoshida (Japanese Wood-block Printing, p. 112) wrote about this technique/effect: "This is a kind of printing in which lines produced by the baren are shown. The baren is so made as to easily produce baren-suji. In fact, it is in the nature of the pad to produce these lines on account of the angular projections of the cord contained in it, and these projections are essential in driving the pigment into the paper. But in olden times the printers were required not to show such lines in the print; it required long and laborious practice to eliminate these lines which were considered defects in the printing." A totally flat effect can easily be the result of multiple passes with the baren. "In order to produce baren-suji, it is better to use a small quantity of pigment on the block, and the printing should not be given too much strength, nor too many strokes." Yoshida continues: "For ordinary purposes it is best to work with the baren of eight-strand cord, having the fibre of its bamboo-sheath covering running in the same direction as that of the paper. But in case baren-suji are desired the baren of sixteen-strand cord should be used in the direction of the grain, or across it, or with a circular motion. If the paper is rubbed across the fibre, it is liable to peel, especially when too wet. This difficulty is overcome when the paper is hard. Thus it is necessary to take advantage of the time when the paper is dry to print baren-suji." On page 113 Yoshida notes the distinctions between different types of baren: "The baren with a sixteen-strand cord is rough and coarse; one with an eight-strand cord is more delicate. But one with a four-strand cord is hardly angular enough to be used for producing baren lines. It must also be bourne in mind that when the baren is fresh, the lines are more distinct, leaving white spaces between the lines. When the baren is old, the lines will be somewhat blurred." The artist/author also says that the baren-suji should be printed early "...before the paper is compressed with many impressions." Then Yoshida adds that, of course, this effect could be printed at the end according to look the printer is trying to achieve. On page 149 it states: "In order to give a soft effect the marks of the baren are also utilized. The repetition one on top of the other produces a soft tone. In order to obtain the effect of mist the baren marks which are made alike over the objects will prove very efficacious, giving these objects an appearance of receding into the distance." |

|

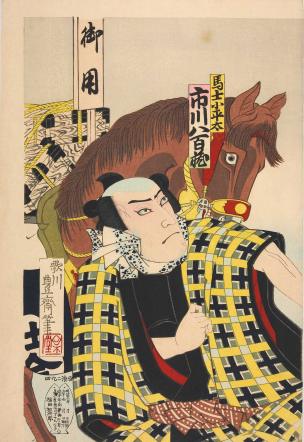

Bashi |

馬士

ばし |

Packhorse driver

To the left is a kabuki representation of an actor, Ichikawa Yaozo VII (七代目市川八百蔵: 1860-1936) as a bashi. It is from the collection of Ritsumeikan University and is by Utagawa Toyosai, dated 1904. |

| Bat motif |

|

By and large bats are used as a very positive motif indicating something propitious like happiness.

In the image to the left of the bat is paired with a blue and white manji, i.e., swastika motif. Happiness is joined here to long life.

The blue and white manji decorated under-robes are often seen in ukiyo-e prints featuring 'good' people as opposed to villains or as George W. Bush would say 'evil doers'.

This image was sent to us courtesy of our friend M. Thanks M! |

|

Batō |

馬頭 ばとう |

Buddhist horse-headed deity (or demon), aka Hayagriva. Most often seen in scenes from hell. The kanji can also be read as Mezu. |

|

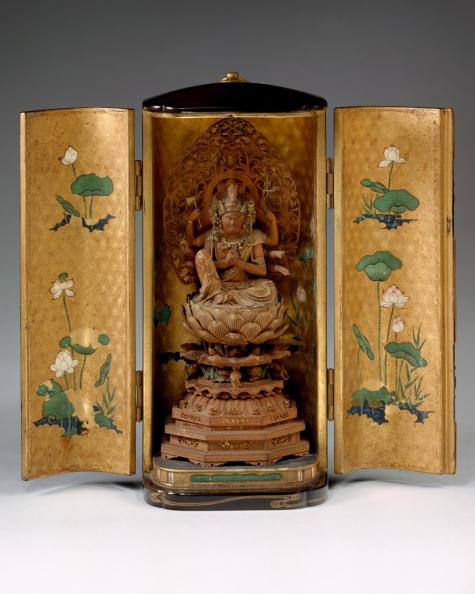

Batō-Kannon |

馬頭観音

ばとうかんのん |

"This Kannon with its horse's head (Batō) is believed to eat trials and tribulations of mankind the way a horse eats grass. Its angry expression serves to admonish people for greed and laziness." Quoted from: Illsustrated Must-See in Nikko, p.23.

A small portable shrine with a horse-headed Kannon. |

|

Hayagrīva (Batō-Kannon in Japan) means "Horse-Necked One" in Sanskrit. "...an early Buddhist deithy who developed from a yakṣa attendant of Avalokiteśvara into a tantric wrathful deity important in the second diffusion of Buddhism in Tibet. The name "Hayagrīva" belonged to two different Vedic deities, one the enemy of Visnu, another a horse-headed avatāra, or manifestation, of that deity. Eventually the two merged, whence he was absorbed into the Buddhist pantheon. In early Buddhist art, Hayagrīva frequently appears as a yakṣa figure attending Avalokiteśvara [among others].; by the mid-seventh century, however, Hayagrīva had merged with Avalokiteśvara to become a wrathful form of that bodhisattva.... While he does appear with a horse's head in Japan (where he is considered a protective deity of horses), Hayagrīva is customarily shown with a horse head emerging from his flaming hair.... In Mongolia he is primarily worshipped as the god of horses." Quoted from: The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, p. 347. |

||

|

|

||

|

Bekkō |

鼈甲

べっこう

|

"Bekko-zaiku or tortoise-shell work is one of the handicrafts of Japan that developed in the earliest period, and reached its highest stage of perfection in Edo days."

"When the scale [i.e., the shell] is heated it becomes soft, and then the thin upper layer is peeled off. This thin layer which is almost transparent is used for making various artistic and valuable things. By pressing, it can be made to take various shapes."

"...the popular use of bekko seems to have developed in Tokugawa days in the 17th century when women's way of hair dressing changed.

Combs and kogai (hair fasteners came to be made of bekko. Kogai which was at first only a simple long stick became elaborate. There were kogai of silver, gold, ivory and other materials, but bekko kogai was the most expensive, as it had elaborate ornamental pieces at both ends, made to represent flowers, butterflies and other shapes." (Quotes from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, p. 1)

Bekkō "...pieces are soaked in water for softning, layered, then shaped over wet wood and pressed between metal iron molds heated to between 100 and 150ºC (212º-304ºF). It can also be softened by heat before being molded into shape. These techniques are uniquely Japanese." (Quoted from: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 8, p. 80, entry by Nakasato Toshikatsu) 1 |

|

There were several attempts during the Edo period to ban the import of tortoiseshell to be used for luxury items. "a very popular material, so in response, merchants changed the name of the product, from taima, to bekko, the common term today, to continue to sell tortoiseshell without attracting the attention of authorities..." Quoted from: Asian Material Culture, essay by Martha Chaiklin, p. 51.

Above is a photo of an Eretmochelys imbricata posted at commons.wikimedia by B. navez.

"Perhaps the material most commonly associated with hair ornaments was tortoiseshell. It is strong but light and the yellow and brown tones are fairly neutral, which meant they could be used by any age in any season. The tortoiseshell used in hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata), so called for their protruding mouths. These turtles are found only in tropical waters. Tortoiseshell was not used widely in ancient Japan..." Ibid., p. 52

Above is a photo of an hawksbill in the Hamburg Deutsches Zollmuseum. It was posted at commons.wikimedia by Andreas Praefcke.

"Imitation tortoiseshell made from water buffalo horn was sometimes called Chosen (Korean) tortoiseshell. The demand for these imitations even caused water buffalo horn to become quite expensive so that by the 1780s, cow horn was used. Horse hoof was also a popular alternative around this time. These imitations were so clever that it as difficult for an amateur to discern its veracity but the horse hoof dulled after a couple years..." Ibid., p. 53 |

||

|

|

||

|

Bengara |

弁柄 ベンガラ

|

Bengara is the name of the deep red used on torii, bridges and other sacred elements at Shinto shrines. Its use was not restricted to these shrines, but it is there that it plays its most distinctive role. Bengara is the Japanese pronunciation of Bengal where an iron oxide rich soil was found which produces this particular color.

I want to thank a new contributor K. for bringing this term to my attention. Thanks K!

The doctored image to the left is from a print by Yoshitoshi. I altered it to emphasize the dramatic red of the bridge. 1 |

|

In the abstract for Reproduction of Japanese Traditional Pigment Based on Iron Oxide Powders With Yellowish Red Color from 2001 it says: "Since the beginning of the 18th century A.D., an artificial iron oxide pigment (hematite, called “bengara” in Japanese) and having a beautiful yellowish red color, has been produced in Japan and applied to pottery, textiles and paintings. However, in 1965 the traditional “bengara” could not be produced anymore, mainly because of environmental pollution.... Traditional “bengara” has been characterized as hematite containing a small amount of Al. The average size of the “bengara” particles is approximately 100 nm. The color becomes more yellowish-red with increasing Al content."

This piece of Calcite-Hematite was posted at commons.wikimedia by Rob Lavinsky.

In a report on iron oxide red from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston it says: "All iron oxide reds are stable, permanent pigments with good tinting strength and are the primary colorant in ochers and siennas."

According to a 2006 article by John Rakovan and Alfredo Petrov there was an ancient process for creating bengara: "The chemical process involved was simple: Piles of sulfide ore were allowed to naturally decompose into vitriols {a mixture of water-soluble metal sulfates), which were easily purified by decanting a water solution after all the insoluble impurities had settled out. After drying out the solution, the crystallized sulfates were burned at a high temperature to drive off sulfur dioxide and sulfuric acid, leaving a finely divided red powder of iron oxide (hematite), enhanced with a little copper oxide (cuprite). This powder was much finer than anything that could be achieved by mechanically grinding hematite or cinnabar, as had been done before the bengara process was invented."

In 1997 three earthenware fragments, believed to be 9-10,000 years old, were found in the central Satsuma peninsula. That would put them in the early Jomon period. The insides were red. "Tatsuo Kobayashi, a professor of archaeology at Kokugakuin University, said that in many cases, the color red was believed by ancient people to have magical powers." Professor Kobayashi believes that bengara was used to create this color. Source: The Japan Times, July 26, 1997 |

||

|

Benibana |

紅花

べにばな

|

Bengibana or safflower: On April 4, 2009 our great contributor 英渓 (Eikei) drew our attention to the Benibana Museum in Kahoku town (河北町) in the Yamagata prefecture. That spurred us to add this entry on the source of one of the great early colorants used in ukiyo prints. ¶ During the Edo period theses flowers were processed into cakes which were shipped to Kyōto to be used for cosmetics for the lips and cheeks and as fabric dye. Both yellow and red coloring was produced, but it was the latter which was the most expensive because it took ten times the amount needed for the yellow. ¶ Safflower based oni (黄丹 or おうに) or a yellow-red is still used for dyeing the ritual robes of the crown prince. Benibana was also used in the production of a special color to dye the lining of robes worn only by the Emperor. No one else is allowed to wear this color.

|

|

Safflower was not native to Japan, but was imported from China around the same time the Japanese were adopting and adapting many of its neighbors cultural practices. One example is the use of certain colors used to represent court rankings. Nor was safflower native to China but had to be imported from areas to its west. In fact, it was used in ancient Egypt and clearly valued there too. "In Egypt, dye made from safflower was used to colour cotton and silk as well as ceremonial ointment used in religious ceremonies and to anoint mummies prior to binding. Safflower seeds and packets and garlands of florets have been found with 4000- year-old mummies (Weiss 1971). The oil was used as an unguent and for lighting." It was also uses as a purgative, to produce sweating to break fevers and in cooking in general from Africa to India. Carthamin dye was used in carpet weaving and "Hebrew writings since the 2nd century AD have described the use of tablets of carthamin dye for food colouring, rouge and medicine (Weiss 1983)." ¶In some locales it was used to prevent miscarriages or for fertility. "Until this century, soot from charred safflower plants was used to make kohl, the Egyptian cosmetic (Weiss 1983)." At times safflower would be substituted for saffron, the world's most expensive spice. "Until this century, when cheaper aniline dyes became available, safflower was mainly grown for dye. The water-soluble yellow dye, carthamidin, and a water-insoluble red dye, carthamin, which is readily soluble in alkali, can be obtained from safflower florets (Weiss 1983). Yellow florets contain little or no red dye (Smith 1996). Dye manufacture has virtually ceased in Asia, but dye is still prepared on a small scale for traditional and religious occasions." It is best to collect flowers in the morning, dry them in the shade and then soak them in acidulated water for 3 to 4 days to extract the dye. (Source and quotes for the above paragraph are from: "Safflower: Carthamus tinctorius L., by Li Dajue and Hans Henning-Mündel, The International Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRI), Rome, 1996)

The references to Weiss 1983 are for E. A. Weiss, Oilseed Crops, Chapter 6, "Safflower", Longman Group Limited, Longman House, London, UK. Pp. 216-281. The source for Smith 1996 is for J. R. Smith, Safflower, AOCS Press, Champaign, Illinois, p. 624

These images are shown courtesy of Shu Suehiro at http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm.

In an 1889 article entitled "The Industries of Japan: Together with an Account of Its Agriculture, Forestry, Arts, and Commerce" by Johannes Justus Rein (pp. 176-7) it states "We know now for certain that the saw-wort [i.e., safflower] was raised in Egypty more than 3,500 years ago, since Schweinfurth recognised it in the garland which Brugsch and Maspero, in 1881 found in the newly-discovered graves of the Pharoahs at Thebes, on the breast of Ahmes II., the conqueror of Hycsos."

See also our entry on sasabeni on our Ro thru Seigle index/glossary page.

Egyptian mummy cloth dyed both yellow and red using safflower has been found. "Carthamine, the red colouring matter first isolated by Schlieper in 1846, received little attention until 1910, when Kamataka and Perkin succeeded in obtaining it in a crystalline condition. Though possessing a more complex formula than curcumin, a certain resemblance exists between these colouring matters, as regards the simple nature of their decomposition products, and there is reason to suppose that they may be structurally related." (Source and quote from: The Natural Organic Colouring Matters by Arthur George Perkin, 1918, p. 14)

See also our entry on ukon with a discussion of curcumin at http://printsofjapan.wordpress.com/2009/06/11/ukon-鬱金-turmeric/. |

||

|

|

||

|

Beni-e |

紅絵

べにえ |

An early form of hand painted Japanese print where the dominant color is the red derived from the petals of the safflower plant or dyer's thistle (Carthamus tinctorius).

Rebecca Salter notes that beni was a very fugitive color. It was "mixed with an acidic liquid derived from the half-dried outer layer of the stones of Japanese plums (ume) and allowed to ferment. The mixture is then dried in the sun into cakes. From around 1715 it was used in hand-colouring even though it was almost as expensive as gold. It seems the brushes used were not washed for that reason!"

Other cultures used equally or more expensive materials in producing artworks. The Europeans, for example, used lapis lazuli which was worth more than its weight in gold to make a celestial blue color. (Quoted from: Japanese Woodblock Printing, by Rebecca Salter, University of Hawai'i Press, 2001, p. 27)

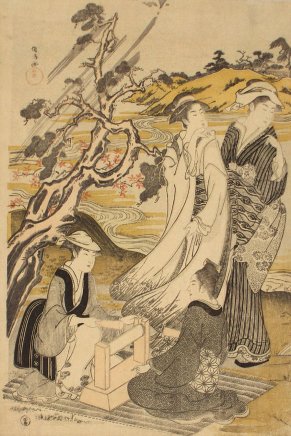

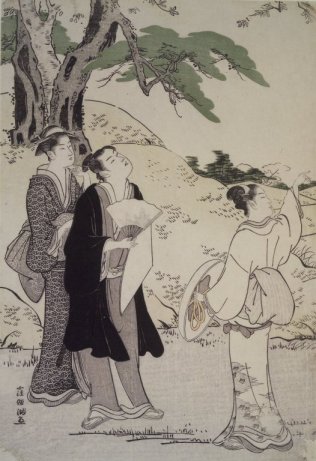

To the left and below are three details from a single, beni-e print by Shigenaga illustrating a party of people gathered for cherry blossom viewing. Dating from the 1720s to 30s this is an extremely rare print. At some point we will devote a separate page to it where you will be able to see it in a larger format. This image has been sent to us courtesy of one of our contributors. For this we are immensely grateful. Truly!

According to the Britannica this technique was used from 1710 until 1742 when the first two-colored printing, i.e.,benizuri-e, appeared in the marketplace. |

|

Benigirai |

紅嫌い

べにぎらい

|

In The Passionate Art of Utagawa Utamaro Timothy Clark (text volume, p. 95) refers to "...the so-called beni-girai ('crimson avoiding') style."

'So-called' seems to be the key word here. So far I have been unable to find out anything about this term other than the fact that it describes a print which does not include red inks. Whether this is intentional as an aesthetic choice or for some other reason I haven't a clue nor am I sure does anyone else. This may simply be a term which could be applied very loosely.

In a 2011 doctoral thesis by

Kazuko Kameda-Madar at the University of British Columbia it says that

Shunman chose "... a mode of visual expression that uses exclusively subtle

colors – purples and greys – and avoids bright colors such as red. The

reduced color tone of benigirai-e, which contrasts with Harunobu‟s

bright color application, had been understood by earlier modern scholars as

a consequence of the Kansei Reform 寛政の改革 (1787-93) that

We found both Shunman examples shown here at commons.wikimedia. The one above is from the collection of the Brooklyn Museum. |

|

Benkan |

冕冠

べんかん |

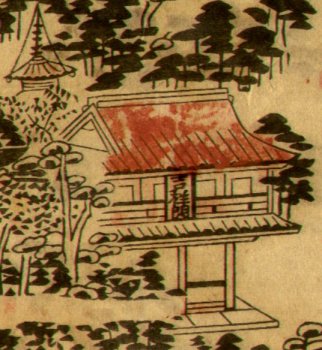

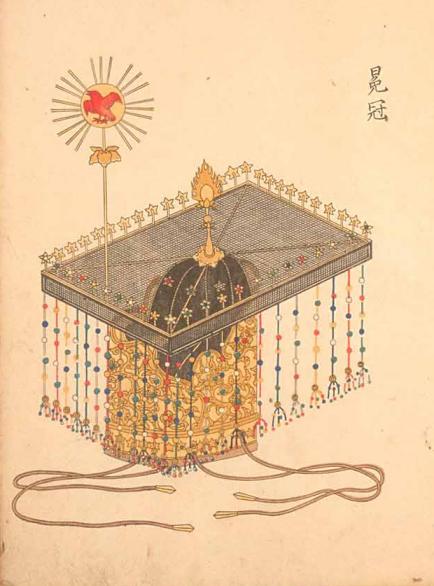

Chinese-styled crown - "...Shōmu was reportedly the first Japanese monarch to don full Chinese ceremonial garb, including the crown of streaming jewels, in the New Year court assembly of 732..."

The printed image to the left is from the early to mid-19th. It illustrates a traditional benkan. We found it at Commons Wikimedia. It is described as the Crown of the Heavenly Sovereign. |

|

Ben(zai)ten |

弁(財)天

べん(ざい)てん |

The only goddess among the Seven Propitious Gods. She is the patron of the arts and wisdom. One of the main shrines devoted to her is on Enoshima near Kamakura. 1

The image to the left was posted at Flickr by Shichiroku. The doctored Kuniyoshi detail shown above is from our web log page dedicated to this goddess. Click on it to learn a ton more. |

|

Bero-ai |

ベロ藍

|

The Japanese name for the Prussian or Berlin blue pigment. It was created by Heinrich Diesbach in 1704. This was first of the modern, artificial pigments. He was trying to make a new red at the time because much of this concoction contained cattle blood, but he ended up with a deep blue. By the 1820s this new color was being used in Japanese woodblock printmaking. 1 |

|

"The exact date when the synthetic pigment [bero-ai or Prussian Blue] was first imported into Japan by the Dutch is not known. The ukiyo-e scholar Yoshida Teruji quotes an Edo bookseller and haiku poet Seisōdō Tōho as saying in a book of essays that Prussian blue was introduced in 1829 (Bunsei 12) by the artist Ōoka Umpō (1765-1848), who used it in a surimono. Soon afterwards it was taken up by all surimono artists. Seeing the popularity of these prints, the fan-print publisher Iseya Sōbei first used the pigment the following year on prints by Keisai Eisen. ¶ While Tōho's reminiscences may be true for completely blue-printed works (aizuri-e) - an aizuri-e fan print by Kunisada is seal-dated 5/1830... Bero-ai in fact appears to have been used even earlier, but only in small areas of the design and normally to delineate luxury products and accessories. In Kunisada's works the earliest such use appears to be in a painting of 1822-23... Kunisda's fan print of 1825... and an Osaka surimono of he same year have the blue, again in limited areas. The blue is also found on prints collected by Philipp Franz von Siebold, a member of the Dutch trading mission at Dejima island from 1823 until 1829. The pristine quality of these prints is such that von Siebold probably acquired them directly from the publishers when he made an official visit to Edo in 1826. ¶ From all the evidence it seems likely that when first brought in by the Dutch, the synthetic pigment was a luxury, high-priced import. This would explain why it is first found on paintings and then on elaborate, surimono-style prints created for the connoisseur market... and in small areas of expensive early editions of full-size prints... With the success of the color and its import in greater amounts, the price would have fallen, enabling publishers to use it for monochromatic blue prints. This is what occurred late in Kunisada's life when aniline dyes were imported from Germany. At first they were expensive and used only for luxury editions... then, during the Meiji period (1868-1912), the price fell and the colors became widely available." Quoted from: Kunisada's World by Sebastian Izzard, p. 29.

In an article, 'Hokusai and the Blue Revolution', Henry D. Smith II wrote: "In Dutch trading records of the time, the pigment was known a “Berlyns biaauw' from which came the Japanese transcription 'bereinburaau' that appeared in Gennai's account. All succeeding Japanese terms were derived from 'Berlin'. The earliest known appearance of the abbreviated form 'bero' was in a letter of the Edo painter lshikawa Tairō in about 1800, and it is this term that seems to have become the most common among artists: this is the word, for example, that appears frequently in Hokusai's painting manual of 1848, Ehon soishiki-tsū (Picture Manual on the Use of Colouring). Tōho in his account used the longer form 'berorin', while other writers used 'heru' (or 'beru", or 'peru'). (It is worth noting, incidentally, that 'bero-oi' ['Berlin indigo'], which is widely used in modern Japanese accounts, appears in no surviving Edo texts, and is probably a modem coinage.) Finally, the Sino-Japanese term used for me pigment in the Nagasaki trade was konjō, which combines two characters for 'blue' and does not refer to a place of origin."

Smith added that Berlin blue "...can both duplicate and extend the intensity and range of tones possible with either of those colours. Berlin blue may initially have cost more by weight than the domestic organic blue, but its high tinting strength meant that a tiny amount went a long way. From a printer's standpoint Berlin blue was in every way superior to the existing blue colorants, which it would almost totally displace by the early Tenpō period."

"...indeed, the use of Berlin blue has not yet been positively identified in any Edo single-sheet nishiki-e that can be firmly dated earlier than the appearance of Eisen's fan print in the summer of 1829, despite claim to the contrary by Sebatian lzzard and Shindō Shigeru." (Ibid.) |

||

|

|

||

|

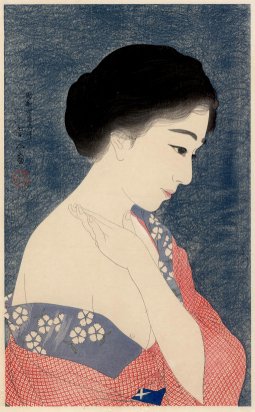

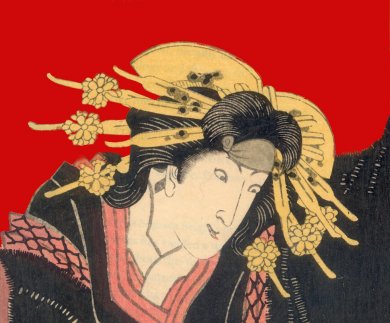

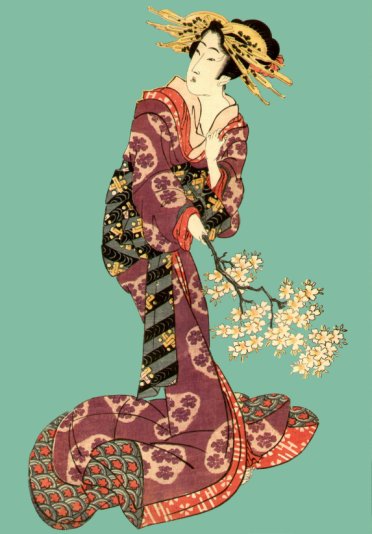

Bijin |

美人

びじん

|

The term bijin has always fascinated me because literally it means 'beautiful person', but now strictly refers to women. The character 人 in isolation means 'man', 'person' or 'people', but combined with 美, the character for beautiful, it applies only to women. Why? Finally I found an plausible answer.

Kittredge Cherry in her Womansword (p. 19) states: "Beauty is female. 'I met a beauty today' generally means the speaker encountered a beautiful woman. Likewise, the Japanese talk about meeting a bijin, literally 'beauty-person' but actually used exclusively for beauties of the female persuasion. In contrast, gender is usually specified in various words for male beauties, such as 'beauty-man' (binan)." [美男 or びなん]

(However, Roger Keyes states it differently - and this is an author who I trust: "The word bijin is ungendered. It means 'beautiful person' and suggests sexual attraction, sometimes dangerous." Quoted from: Ehon: The Artist and the Book in Japan, published by the New York Public Library with the University of Washington Press, 2006, p. 64.)

Frank Turk in his Prints of Japan (p. 117) notes that Michener believed "...that during the period 1660-1860 pictures of beautiful women made up about 40 per cent of the total output of ukiyo-e..." Turk concurred.

Recently I told a friend that I was going to add an entry on bijin-ga. He said something about them only being pictures of prostitutes. I told him that was wrong, but not completely so. Since so many of the great beauties of their day portrayed by artists were frequently famous courtesans I could see why he believed that.

Julia Hutt in her essay "The Golden Age, 1780-1810" in Ukiyo-e to Shin Hanga: The Art of Japanese Woodblock Prints (p. 83) notes: "In the context of ukiyo-e art, the term bijin is used generically to refer to well-groomed women from many social levels employed in multifarious activities." She continues: "On the one hand are those which depict respectable women going about their daily business, such as carrying out mundane domestic activities or taking part in outings to view cherry blossoms, to the seaside or to a temple." On the other hand... Well, you can guess what those women were doing.

The Eizan details to the left are indeed images of the tayu - the highest class of courtesan - Misado of the Tama-ya. This was sent to us by our generous contributor E. Thanks E! |

|

Miya Elise Mizuta in her article "美人 Bijin/Beauty" from 2013 started off with a Japanese proverb followed by her opening statement:

|

||

|

|

||

|

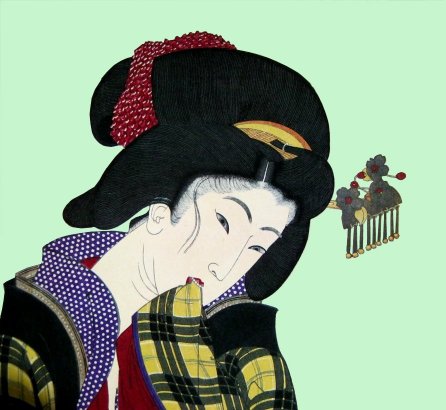

Bira bira kanzashi |

びらびら簪

びらびらかんざし |

A type of hairpin with dangling metal parts which give the sound of tinkling when they move. The term 'bira bira' is said to be onomatopoetic. In Four Centuries of Fashion: Classical Kimono from the Kyoto National Museum it says on page 142: "They began to appear during the Gembun and Kampo eras (1736-1743), and in the Bunka Bunsei eras (1804-1830) they were in fashion. Kanazashi with lovely and delicate dangling objects were much favored by young maidens who looked beautiful in furisode (kosode with swinging sleeves), and by young newlywed women. For some reason, elaborate kanzashi dropped out of fashion and disappeared completely during the Bunkyu period (1861-63)."

Both examples shown here are isolated from prints by Yoshitoshi. |

|

Bishamon |

毘沙門

びしゃもん |

One of the Seven Propitious Gods. He is a god of warfare. Also known as Tamonten (多聞天). In India he was referred to as Vaīśravana, one of the four lokapala or 'world-protectors'. His region is that of the North.

Alice Getty, on the other hand, states definitively "The Japanese Vaīśravana is not, however, the god of War, but the God of Good Fortune..."

The book illustration image to the left was sent to us by one of our correspondents, E. It is said to date from circa 1690 and is attributed to Yoshida Hambei from the "Nanto Daibutsen goengi". Thanks E! |

|

"Dressed in armor, wielding a spear, and holding a pagoda in the upturned palm of his left hand [*], Bishamonten is a Buddhist guardian deity, one of the Four Heavenly Kings (Shitennō [四天王]). As one who protects Buddhism against natural disasters and human enemies, Bishamonten was described as having many attendants, all of whom could help those who call upon him: troubles will cease, wealth will increase, and all wishes will be fulfilled." In the Sutra of the Golden Light (金光明経) Bishamonten explains to the Buddha the advantages of reciting his wish-fulfilling mantra. Among its benefits it can free humans of suffering and bring them wealth and happiness. ¶ "Bishamonten, who was sometimes identified with Konpira, the Shinto deity of ships and sailors, displays the protean character of a deity who can assume different forms to protect and bless people in accord with their wishes." (Source and quotes from: Practically Religious: Worldly Benefits and the Common Religion of Japan, by Ian Reader and George Joji Tanabe, University of Hawaii Press, 1998, pp. 158-9)

* I cannot account for the differences between the image above and the description below it. The statue of Bishamon is holding the pagoda in its right hand and not its left. Perhaps the image has been reversed. Perhaps not. These kind of irksome disparities occur frequently and are difficult to reconcile. Also, note that the photo of this impressive wood sculpture was taken by 663Highland and posted at http://commons.wikimedia.org/. I altered the background to make figure stand out more.

Now for the right-hand-pagoda-holding Bishamon: "...guardian of the north, giver of wealth, and the stupa he holds in his right hand supposedly contains money. The centipede is associated with him." [A centipede? Now there is a new twist. What I didn't know - or didn't remember knowing - is that dragons - or at least one - were afraid of centipedes.] (Source: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 5, p. 296, entry by E. Dale Saunders)

Henri Joly said in his Legend in Japanese Art (published by John Lane Co., p. 22) that he is "...the equivalent of Kuvera the Hindoo god of riches... shown in full armour, with a fierce expression, carrying in his right hand a small pagoda shaped shrine, and in the left a lance. The latter attribute is responsible for his erroneous description amongst the Gods of war." At least we have another vote for a right-handed stupa. Later Joly describes Bishamon as "... depicted with a blue face, clad in armour and carrying a pagoda in the left hand, a sceptre in the right one... or a lance, or three-pointed halberd..." Ibid., p. 140) Right-handed pagoda again? However, in Joly's defense he may be quoting Eitel, but even this is unclear.¶Joly and others note the connection between Prince Shotoku (572-621: 聖徳太子) and Bishamon. Like all other accounts there are several variations and here is Joly's: Shotoku, a defender of Buddhism, was struggling with Moriya, a non-Buddhist. Bishamon appeared before Shotoku as an old man and for whatever reason that won the day. ¶Bishamon also rules over the yakshas which are semi-divine beings which range from troublesome to helpful.

In an 1886 catalogue compiled by William Anderson for the collection of Chinese and Japanese paintings in the British Museum Bishamon is said to have saved the life of Shotoku when the god had taken the form of an old man. "This story, however, does not imply that Bishamon was a Buddhist Mars, but merely that success in war was one of the many rewards at his disposal."

In The Gods of Northern Buddhism: Their History and Iconography by Alice Getty (Courier Dover Publications, 1988, p. 167) weighs in on the left-right divide: Bishamon "...is represented with armour ornamented with the seven precious jewels, and is generally standing on one or two demons. In his left hand he holds either a small shrine or flaming pearl, while in his right is a jewelled lance... ¶ The maņi, or jewel, on top of his staff, is believed to signify 'completeness of fortune and virtue' The small caitya, or shrine, represent the Iron Tower in India where Nāgārjuna found the Buddhist scriptures." In an illustration Bishamon "...is represented looking at the shrine, for, as one of the guardians of Buddhism, he must keep watch over its greatest treasures..."

This author doesn't take sides in the "Which hand holds the stupa?" conundrum: "Of the Four Heavenly Kings... who guarded the four directions, Bishamon was considered the most important since he had charge of the north, the direction of the greatest peril in Buddhist cosmology." (Quoted from: Heart's Flower: The Life and Poetry of Shinkei, by Esperanza U. Ramirez-Christensen, Stanford University Press, 1994, pp. 33-4)

Hugo Munsterberg wrote that the earliest woodblock printed image is of Bishamonten. It is in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and dates from 1162. It was found within a statue of Buddha.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Bishamonkikkō |

毘沙門亀甲

びしゃもん.きっこう |

This is the name of the pattern of the armor often seen on the figure Bishamon although it does not appear in the entry immediately above this one. It contains the characters for Bishamon and tortoiseshell.

This photo was posted at Flickr by Stephen Wedgwood.

This is also related to the kensaki (剣先) or sword tip pattern. 1 |

|

Biwa hōshi |

琵琶法師

びわほうし |

Blind itinerant Buddhist priests who performed on the biwa. Donald Keene in his Seeds in the Heart: Japanese Literature from Earliest Times to the Late Sixteenth Century (p. 617) notes that sometimes a man who performs on the biwa, wears the robes, and has the shaven head is not necessarily a hōshi, but may pass for one. Later he notes: "The first problem is the significance of hōshi, a term that normally designated a priest, but was also used for such persons as biwa hōshi. Some recited The Tale of the Heike, but others amused people who paid them with tales of their own invention, songs, and other displays of talent." (Ibid., p. 878)

|

|

Terry Kawashima in Writing Margins: The Textual Construction of Gender in Heian and Kamakura Japan (p. 277) notes that the biwa hōshi may have been responsible for exorcising the vengeful spirits of defeated warriors.

Chanting of the Tales of Heike to the accompaniment of a biwa is referred to as heikyoku (平曲).

Lafcadio Hearn speculated about the origin of the term biwa hōshi: "...it is possible that it may have been suggested by the fact that 'lute-priests' as well as blind shampooers had their heads shaven, like Buddhist priests." Elsewhere Hearn tells the story of Hōichi (芳一) the Earless who was a blind biwa player "...and it is said that when he sang the song of the battle of Dan-no-ura, 'even the goblins could not refrain from tears.' "

There is a Nō play, Semimaru (蝉丸), - probably by Zeami - which deals with a biwa hōshi. Semimaru, the fourth son of the Emperor Daigo (醍醐天皇: 885-930) has been blind from birth. He is thought to be blind because of transgressions in a former life. For this reason the prince is banished from the Court, taken to Mt. Osaka, has his head shaved and is given his biwa as his only companion. The prince questions how his father who is such a good man could do such a cruel thing to him. The man who led Semimaru to the mountain explains that what the Emperor has done is an act of kindness because it will help lead to the prince's salvation. Around the same time Semimaru's sister, the princess Sakagami, has been banished because she is mad. She wanders distraught on Mt. Osaka. When she hears the sound of a lute she is drawn to it. The brother and sister are reunited in their misery, but eventually she wanders off somewhat consoled and he is left alone "...like a frightened bird..." as one commentator described him. According to an University of Virginia web site the story of Semimaru appeared as early as the 12th c. in the Konjaku monogatari but had no historical basis. There were also considerable differences from that of the Nō production. By the time of the Heike monogatari Semimaru had become a prince. Zeami added the princess. Then it is noted that "Semimaru is perhaps the most tragic play of the entire No repetory." During the 1930s and 40s this play was self-censored because of the offense it might give the Imperial household. Susan Matisoff in her introduction to The Legend of Semimaru Blind Musician of Japan (pp. xiv-xv) said that "...heads of the major schools of Nō [decided] to drop the play from the performance repetoires of some schools and the pressures leading to the creation of textual revisions. A reworked Kanze school version of the play was produced in 1935 to deal with the problem. The solution involved re-identifying Semimaru simply as a famous biwa hōshi, while Sakagami retains her status as a 'princess' but is recast as an orphaned child of Zhou dynasty Chinese imperial lineage."

See also our entry on mekura or blindness. |

||

|

|

||

|

Blue and white porcelain ( called aobana in Japanese) |

Detail from a Ming vase below

|

An innovative 13th c. use of cobalt for underglaze decoration 1

On 10/5/12 we finally added the Japanese term for blue and white porcelain, sometsuke, to our Si thru Tengai page.

See our entry on 'aobana'. |

|

LINKS TO OUR OTHER INDEX/GLOSSARY PAGES Click on any of the pages listed below!

|

||

HOME

HOME