|

|

|

JAPANESE PRINTS A MILLION QUESTIONS TWO MILLION MYSTERIES |

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

|

Port Townsend, Washington |

|

A CLICKABLE INDEX/GLOSSARY (Hopefully this will be an ever changing and growing list.)

A THRU Bl |

|

|

The gold koban coin on a blue ground is being used to mark additions made in June 2008. The red on white kiku mon was used in May. |

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

Ageboshi, Ageha no cho, Ai, Aigami, Aizuri-e, Aka-e, Amagatsu, Amanojaku, Ame, Andon and Ankō

揚帽子, 揚羽蝶, 藍, 藍紙, 藍摺絵, 赤絵, 天児, 天邪鬼, 雨, アメリカ原住民, 行灯, 鮟鱇

あげぼうし, あげはのちょう, あい, あいがみ, あいずりえ, あかえ, あまがつ, あまのじゃく, あめ, あんどん and あんこう |

|

|

TERM/NAME |

KANJI/KANA |

DESCRIPTION/ DEFINITION/ CATEGORY Click on the yellow numbers to go to linked pages. |

|

Age-bōshi |

揚帽子

あげぼうし |

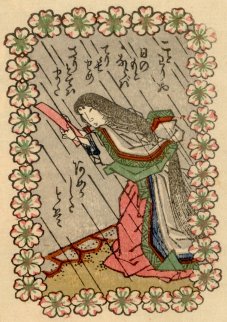

A head cloth worn by women to keep their oiled hair clean from dust and properly coiffed during an outing. Very similar to the headdress worn by a bride. (See our entry on tsunokakushi.)

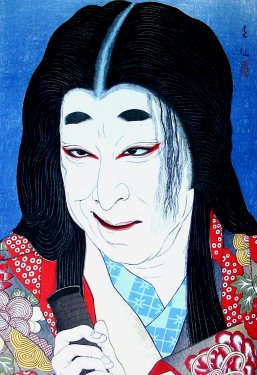

The image to the left is a detail from a print by Kiyonaga showing an actor in the role of a female samurai. |

|

Ageha no cho |

揚羽蝶 あげはのちょう |

"...a butterfly with its wings raised...was the alternate crest of Segawa Kikunojo." |

|

Ai |

藍

あい

|

Japanese indigo from the plant Polygonum tinctorium or dyer's knotweed - it is also referred to as tade ai: Indigo as a color can be produced from any number of plants, but here we are limiting ourselves to just one which was frequently used as a colorant in woodblock prints and fabrics. In Kosode: 16Th-19th Century Textiles from the Nomura Collection: 16th-19th Century Textiles from the Nomura Collection by Amanda Mayer Stinchecum (pp. 202-3) notes that this plant grows throughout Japan, but especially in Shikoku. The leaves which contain indigotin and should be harvested in July through September and in November before flowering. The fresh leaves should be fermented or dried and/or composted.

In the earliest times the Japanese indigo leaves were chopped up in water. Later during the Nara-Heian periods they were fermented in water. During the Edo period they were fermented in lye water combined with other ingredients.

The resultant colors ranged from a pale to bright blue according to the number of leaves per quantity of water. Combined with other dyes a larger range of colors could be produced including lavender, fake purple and black.

In a web page posted by the University of Bristol "...Dr. David Hill of the School of Biological Sciences describes his quest to provide the modern world with a natural alternative to synthetic dyes." This is fascinating stuff. Especially his information about the source of indigo itself: "Indigo producing plants do not actually contain indigo but the leaves of these plants before they flower contain a substance which, when extracted from the leaf, forms indigo by absorbing oxygen from the air. Indigo is notoriously insoluble in nearly all commonly used solvents, and especially in water, so the indigo formed in the extracts settles out as a precipitate quite easily."

That might explain something I noticed while researching this subject. While searching for additional material to post here I ran across a beautiful page in English from a German language web site operated by Dorothea Fischer. After a brief correspondence she gave me permission to post the three images to the left. However, for a fuller and richer understanding of the entire process - especially as it pertains to fabrics, but clearly not greatly removed from the methods for producing early ukiyo indigo inks - I would urge you to visit her web page devoted to this topic. It is astounding.

http://www.lustauffarben.de/faerben-faerberknoeterich-englisch.html

I want to thank Ms. Fischer - and her friend Friedl who helped in our correspondence - for her contribution in creating this entry.

|

|

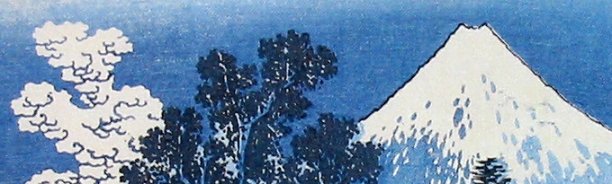

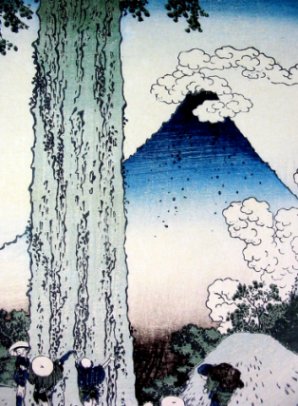

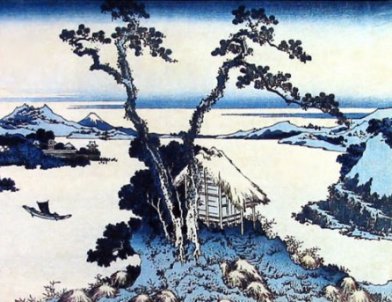

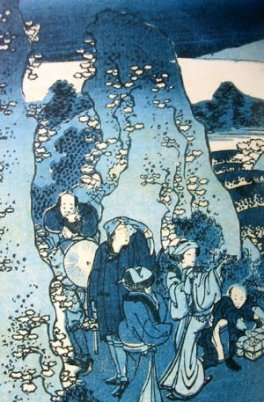

There is a fascinating scientific article published in 2006 by the Japan Society for Analytical Chemistryentitled: "Non-Destructive Identification of Blue Colorants in Ukiyo-e Prints by Visible-Near Infrared Reflection Spectrum Obtained with a Portable Spectrophotomer Using Fiber Optics". They inspected a set of prints from the "36 Views of Fuji" by Hokusai dated ca. 1830-33. Using a non-invasive technique they studied the use of aigami, ai (indigo) and the imported colorant Prussian blue. What they discovered was amazing - at least for me. The keyblocks were all printed with indigo "...while all color blocks were printed with Prussian blue." Prior to this study it had been assumed that all of the keyblock lines had also been Prussian blue, but clearly this was not the case. While this information may not interest everyone it is nevertheless remarkable for what it tells us about the production of what may be the most famous series of Japanese prints ever. The same exact technique was used for Hokusai's famous waterfall series Shokoku taki meguri. There were no exceptions. Both examples shown here are details from the Fuji series.

One last point: The scientists who wrote this article refer to the source of indigo as knotweed, i.e., Polygonum tinctorium, and not as dyer's knotweed as mentioned above. |

||

|

|

||

|

Aigami |

藍紙 あいがみ |

An early organic blue made from the dayflower. It fades quickly. Sometimes it fades to an olive gray. (See 'dayflower' listed below.) 1 |

|

Aizuri-e |

藍摺絵

あいずりえ |

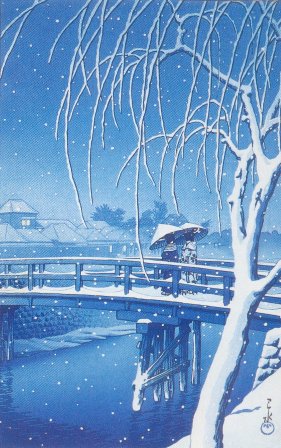

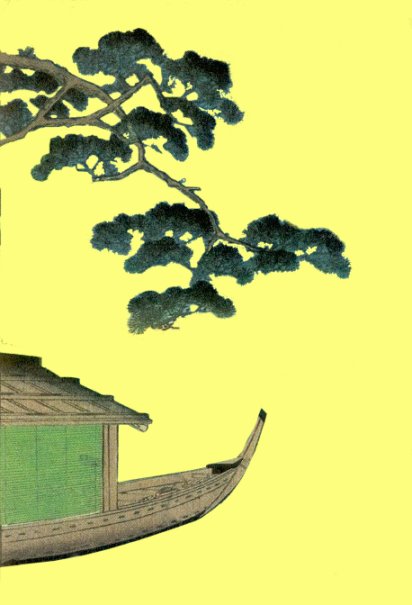

Images printed predominantly in shades of blue. The image to the left is by Eisen and dates from the first half of the 19th century and the Hasui below is from 1933. 1

|

|

Quoted from: Hokusai: Life and Work, by Richard Lane, E. P. Dutton, 1989, pp. 184-5.

Quote from: Japanese Woodblock Prints: A Catalogue of the Mary A. Ainsworth Collection, by Roger Keyes, Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, 1984, p. 42.

In the catalogue entry #439 on p. 185 of the Ainsworth collection Keyes notes that this print was produced to honor the retirement of the actor Nakamura Utaemon III. This "...print is of special historical interest since Prussian blue seems to be used ont ehimmortal's cap and this color, which is used in so many landscape prints, is said not to have been introduced in Edo until 1828."

|

||

|

|

||

|

Aka-e |

赤絵

あかえ |

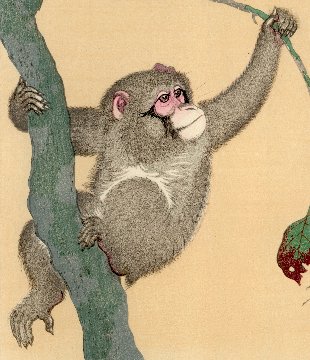

Images printed predominantly in shades of red. These prints were often sold door-to-door by monkey trainers in the 18th c. as talismans against smallpox. This is interesting because monkeys were often kept in stables to ward off horse diseases. It is even said that sometime samurai who wanted to spy on their enemy's camp would pose as monkey trainers just to gain admittance.

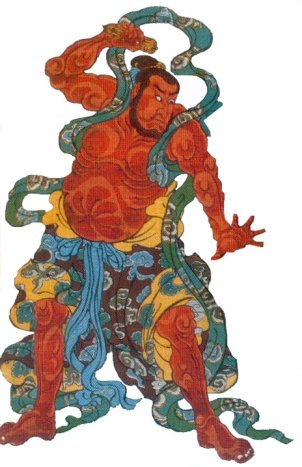

Also referred to as hōsō-e (疱瘡絵 or ほうそうえ) or smallpox pictures. Originally used in China they were adopted in Japan and often featured images of Shoki, the Demon Queller. His image was also shown on the fifth day of the fifth month or Boy's Day as a similar talisman for warding off evil spirits.

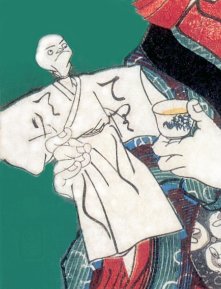

As you can tell from the detail of the Shigemasa (重政 or しげまさ) image to the left a hōsō-e can illustrate something other than a Shoki. In this case it is a Daruma and an owl and an object I can't identify yet. |

|

Akahime |

赤姫 あかひめ |

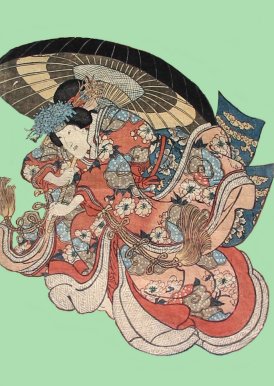

"Red princess": There is a sub-subcategory of female theatrical characters referred to as akahime. "The term is used because so many kabuki princesses and samurai daughters wear red, long-sleeved kimono.... The costume, a kabuki invention having no relation with what actual princesses wore, consists of a robe (uchikake) worn over a kimono of red-figured silk or crepe on which designs of flowers, cherry blossoms, chrysanthemums, clouds, a pattern of long-tailed birds called onagadori, and flowing water are embroidered in gold and silk. The kimono is held together by a brilliant gold brocade obi; at the rear of the obi is a long hanging bow. The wig is a fukiwa type with a large silver flower comb attached to it."

Quoted from: New Kabuki Encyclopedia: A Revised Adaptation of kabuki jiten, compiled by Samuel L. Leiter, 1997, p. 8.

Professor Leiter also pointed out that such a princess "...is typically a physically weak, emotionally vulnerable young lady... She is normally in love with a handsome young lord."

Ibid.

The top image to the left represents Sakurahime by Toyokuni III and the one below is from a Yoshitaki print featuring Yaegakihime. Click on the numbers to the right to see the full images. |

|

Amagatsu |

天児

あまがつ |

"A girl received a

dagger (mikabashi [

Quoted from: The Tale of Genji, by Murasaki Shikibu, translated by Royall Tyler (ロイヤル・タイラー), published by Viking, vol. 1, 2001, p. 350, note #7.

This translation by Royall Tyler is a remarkable accomplishment and a great source for additional material about the world of the Heian period.

|

|

Jane Marie Law in Puppets of Nostalgia published by Princeton University Press in 1997 (p. 35) said: "Amagatsu [heavenly infants] in Heian Japan and continuing until the present, various dolls or effigies have been widely used as substitutes for fetuses, infants, and children to protect them from evil influences and disease."

"They are generically called o-san ningyō (birthing dolls)."

These figures are also referred to as katashiro (形代 or かたしろ) or 'substitute figures'.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Amanojaku |

天邪鬼 あまのじゃく |

The

devil figure beneath a temple guardian; a perverse person.

|

|

Ame |

雨

あめ

|

Rain

Carlos F., one of our friendly contributors, suggested that we add a section on rain. He sent us the detailed image above. It is by Yoshitoshi.. We have added the detail of the frogs in the rain by Kuniyoshi to the left. The full print shows little frogs just above the signature. Below the Kuniyoshi is a detail from a Kunisada print. In time we will add commentary about rain in general and how it was viewed within traditional Japanese culture. This is just our preliminary entry.

I want to thank Carlos for making this suggestion and others which will be added to this site later.

All of the standard dictionaries translate amagaeru (雨蛙 or あまがえ) as tree frog. However, Mock Joya refers to it as a rain frog and that translation is certainly commonsensical. "There are many kinds of frogs in the country. There are grotesque toads, to which are attributed evil spirits. Ao-gaeru, or green frogs are also called ama-gaeru or rain frogs, and it is said that their singing will bring rain." I have no way of knowing if the rain and the green frogs in this picture are an example of this belief, but they may be.

Quoted from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, p. 147.

|

|

Amerindian(s) |

アメリカ原住民

|

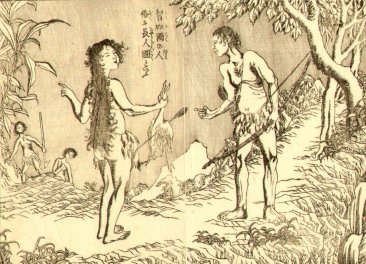

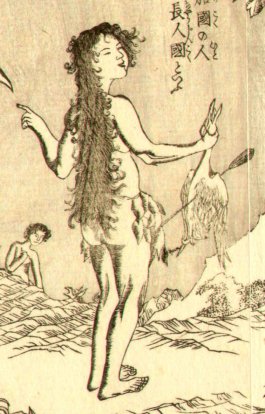

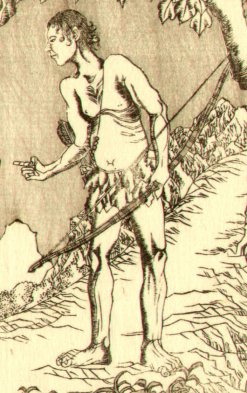

According to the Oxford English Dictionary the term Amerind was not coined until circa 1900 many years after the creation of the images seen to the left. When Sadahide (1807-1873) drew his vision of native born Americans it probably didn't matter to him what they were called. Clearly he was working from a foreign model.

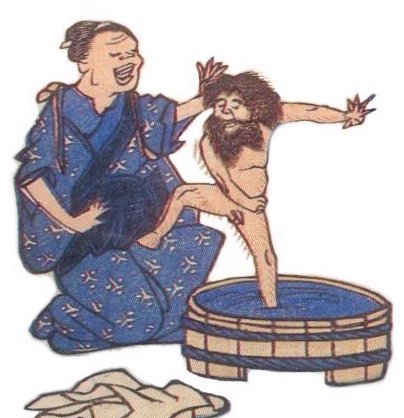

Fanciful concepts of foreigners were nothing new to the Japanese. Europeans were originally referred to as namban (南蛮 or なんばん) which literally translates as 'southern barbarians.' Even after the forced opening of Japan representations of foreigners were often rather exotic. For example, the image at the bottom shows a hirsute, newborn baby boy in his bath. At that time many Japanese believed that a child born of a Japanese mother and a foreign father would come out of the womb looking and acting like this. (Medieval Europeans believed that when Jesus was born he could walk, talk and read and why not?)

Before you are too quick to think the Japanese overly ignorant and superstitious drag out your copy of Herodotus. In Book IV of his "History" he describes a race of people who are born totally bald, flat nosed and with extremely long chins and who grow up that way. This was true of both sexes. But Herodotus was not completely gullible when he stated that "...these bald-headed men say (though I do not believe it) that the mountains are inhabited by men with goats' feet; and that after one has passed beyond these, others are found who sleep through six months of the year." Even this stretched his credulity.

Our great correspondent E. sent us the Sadahide images. E. said: "Leafing through some oddments the other day, I found this double-page bookplate by Sadahide and thought of you! From an 1855 book Meriken shinshi ' News from America' it purports to show how they perceived the native Americans. I don't really think that it will add anything to your index/glossary but I thought you might be amused."

Well, I was obviously more than amused and even though E. is right it doesn't add a lot to these pages I just felt it was too good to pass up. Thanks E!

|

|

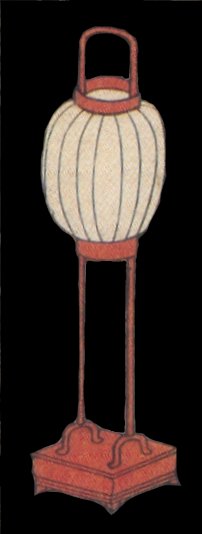

Andon |

行灯

(

あんどん |

Lantern:

Quote from: Dictionary Japanese Culture, by Setsuko Kojima and Gene A. Crane, Heian International, Inc., 1991, p. 9.

Quote from: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 4, p. 368, entry by Nakasato Toshikatsu.

See also our entry on chōchin to contrast the difference between the andon and the hanging lantern. |

|

Ankō |

鮟鱇 あんこう |

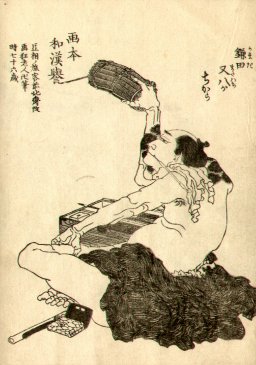

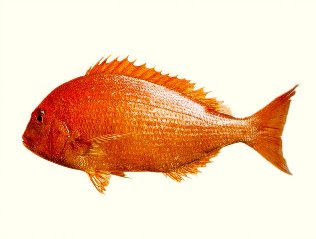

A fish which is referred to by several names: Anglerfish, monkfish, frogfish, et al. An ugly bottom-feeder which was eaten in pre-modern times "...by the common people, especially in Edo (now Tokyo)..." to welcome the arrival of winter.

Kodanasha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 1, 1983, p. 56.

This fish served as an element/prop in certain early, i.e., late 18th c. kabuki plays where they are seen being carried by a string. They are still used in modern cooking. One web site had a great photo of Julia Child preparing one of those ugly suckers. (We will add images when or if they become available.) |

|

|

|

Aoi thru Bl |

|

|

|

Bo thru Da |

De thru Gen |

Ges thru Hic |

Hil thru Hor |

Hos thru I |

|

|

J thru Kakure-gasa |

Kakure-mino thru Ken'yakurei |

|

|

Kesa thru Kodansha |

Kōgai thru Kuruma |

Kutsuwa thru Mok |

Mom thru N |

O thru Ri |

|

Ro Thru Seigle |

Sekichiku thru Sh |

Si thru Tengai |

Tengu thru Tsuzumi |

|

Yakusha thru Z |

3.jpg)

HOME

HOME