|

JAPANESE PRINTS A MILLION QUESTIONS TWO MILLION MYSTERIES |

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

|

Port Townsend, Washington |

|

A CLICKABLE INDEX/GLOSSARY (Hopefully this will be an ever changing and growing list.)

Kesa thru Kuruma |

|

|

The bird on the walnut shell is being used to mark additions made in July 2008. |

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

Kōgai, Kōhone, Koma, Komori, Komugi, Komusō, Kongara Dōji and Seitaka Dōji, Kongōsho, Kōro, Kōshi, Kōshijima, Koshimaki, Koshimino, Kote, Koto, Kotoji, Kotsuzumi, Kuchinashi, Kumagai Jiro Naozane, Kurai-boshi, Kurogo, Kurowatsunagi, Kuro yuri and Kuruma

笄, 河骨, 独楽, 蝙蝠, 小麦, 虚無僧, 矜羯羅童子 & 制た迦童子, 金剛杵, 香炉, 格子, 格子縞, 腰巻, 腰蓑, 腰蓑, 腰蓑, 腰蓑, 腰蓑, 腰蓑, 腰蓑, 腰蓑, 腰蓑, 籠手, 琴, 琴柱, 小鼓, 梔, 熊 谷 次 郎 直 実, 位星, 黒子,郭繋, 黒百合 and 車,

こうがい, |

|

|

TERM/NAME |

KANJI/KANA |

DESCRIPTION/ DEFINITION/ CATEGORY Click on the yellow numbers to go to linked pages. |

|

Kōgai |

笄

こうがい

|

"Long hairpins used for traditional Japanese hairstyles. Originally, kōgai were used by both men and women for parting and styling the hair, as well as for scratching the scalp. During the Edo period (1600-1868), they also functioned as women's hair ornaments, varying in size and decoration. Kōgai were made of wood, bamboo, metal, glass, tortoiseshell, or the shinbones of cranes and were sometimes decorated with gold and silver lacquework."

Quote from: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 4, entry by Hashimoto Sumiko, p. 246.

"An ornament made of shell, worn by married women in the hair; also, two iron rods carried in the scabbard of the short sword, used as chopsticks."

Quote from: A Japanese and English Dictionary with and English and Japanese Index, by James Curtis Hepburn, published by Charles E. Tuttle Co., 1991 edition, p. 218.

The photograph on the bottom has been sent to us by a particularly good friend who has a collection of such things. Notice the difference between the this kōgai and the detail from the Kunichika print above it. Obviously these are considerably different. However, when I tried to find an example in print form like the one on the bottom I was stumped although this is the standard type shown when searched on the Internet. Hmmm?

(See also our entry on kanzashi.) |

|

Kōhone |

河骨

こうほね

|

Cow-lily, spatterdock motif used occasionally for family crests or mons. John W. Dower in his The Elements of Japanese Design (p. 78) speculated that variations of this pattern were used because they closely resembled the more prestigious hemlock or aoi motif.

The choice of coloring is all my own and not taken from any traditional usage.

The photos of the kōhone are provided by Shu Suehiro at http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm. |

|

Koma |

独楽

こま |

The top appears to be native to Japan and may be like so many other things which were invented independently in many different places. It was already popular by the Heian period. Eventually it came to be one of those 'games' played by boys during the New Year's celebration.

What puzzles me, and many things puzzle me, is why, when and how the top became a family crest or mon in Japan. What family would pick it if they weren't top making specialists? When I lived in the Midwest a local university needed to choose a name and mascot for its men's basketball team. They decided on the kangaroo shortened to roo. I understand that they chose it because of that animal's legendary ability to jump and leap, but I couldn't help thinking that it seemed a little silly for a Missouri school to opt for an herbivorous, leaping Australian marsupial which normally could only be seen in American zoos -- unless, of course, one was lucky enough to travel down under and then get off the beach or out of the pub. |

|

Komori |

蝙蝠 こうもり |

Bat - a commonly used motif. See our entry listed under fú. There are two other readings of these characters which also mean bat: kawahori (かわほり) and henpuku (へんぷく). All of these also mean 'opportunist'. 1 |

|

Komugi |

小麦

こむぎ

|

Komugi, i.e., Triticum aestivum is wheat and is the source of the flour used to make udon noodles. We discussed soba and udon noodles on one of our Toyokuni I pages.

Komugiko (小麦粉 or こむぎこ) is the term used for wheat flour.

Also, go to our entry on udon noodles on our U thru Yakata-bune inedex/glossary page.

According to A Dictionary of Japanese Food: Ingredients and Culture by Richard Hosking (p. 82) komugi is also used in making soy sauce and miso.

THE MYTHIC ORIGIN OF WHEAT (AND SERICULTURE): In the Kojiki (古事記 or こじき), as translated by Donald L. Philippi (p. 87), Book I, Chapter 18, Susa-nö-wo approaches the food goddess and asks her for sustenance. "Then Opo-gë-tu-pime took various viands out of her nose, her mouth, and rectum, prepared them in various ways, and presented them to him./Thereupon Paya-susa-nö-wo-nö-mikötö, who had been watching her actions, thought that she was polluting the food before offering it to him and killed Opo-gë-tu-pime-nö-kamï./ In the corpse of the slain deity there grew [various] things: in her head there grew silkworms; in her two eyes there grew rice seeds; in her two ears there grew millet; in her nose there grew red beans; in her genitals there grew wheat; in her rectum there grew soy beans."

In the Nihon shoki (日本書紀 or にほんしょき) the version is somewhat different. In that one the Sun goddess is angered by the Moon deity who slays the food goddess. From the head comes cattle and horses, but wheat still originates in the genitals.

The entry on wheat and barley by Hoshikawa Kiyochika in the Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan (vol. 8, p. 251) gives an alternative source to the ones mentioned above: "Both of these grains were introduced to Japan at nearly the same time in the 3rd or 4th century AD from China."

The images to the left are being shown courtesy of Shu Suehiro at http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm. We would urge you to visit that valuable site. |

|

Komusō |

虚無僧

こむそう |

A wandering mendicant Buddhist Zen monk of the Fuke subgroup of the Rinzai ( 臨済 or りんざい) sect. They wear large sedge hats, tengai, which hide their identities and play the Japanese flute or shakuhachi. Always dressed in their priests robes and large hat this became a favorite disguise for lovers, spies and criminals as was frequently portrayed in the kabuki theater.

According to the Dictionary of Japanese Culture by Setsuko Kojima and Gene A. Crane (p. 185) these strolling priests made their first appearance during the Muromachi period (1336-1568). One of the later give aways that the monk was not really a monk, but a disguised samurai was the sword they carried at their side.

Mock Joya states that the monks head was completely covered because they were not allowed to show their faces outside of their monasteries. The reason so many samurai adopted this costume came about from the fact that they had fled to the Fuke monasteries for protection and chose to dress like the monks when they went out into the world. Although the Fuke sect was dissolved by the Meiji administration near the beginning of its term this didn't totally stop beggars from wearing the same guise because the public continued to feed and support them.

Source: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, p. 545.

The image to the left is a detail from the Gyōsho Tōkaidō series by Hiroshige. Here two kamusō are encountering a peddler. |

|

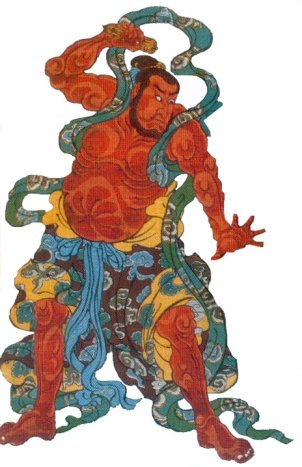

Kongara Dōji and Seitaka Dōji |

矜羯羅童子 こんがら.どうじ & 制た迦童子 せいたか.どうじ |

Fudō Myōō, one of the five wise kings of Buddhism, is almost always shown as with his two attendants Kongara and Seitaka, at least as far as ukiyo prints were involved. There are several references in certain esoteric Buddhist sutras which mentions a total of eight attendants. In fact, there were sculptures of the Kamakura period (1192-1333) created for temples which showed Fudō Myōō amidst this larger grouping. |

|

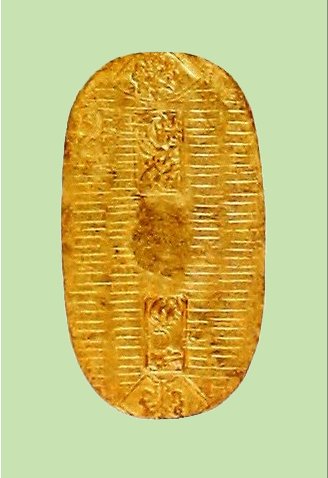

Kongōsho |

金剛杵

こんごうしょ |

Kongōsho is the Japanese word for the vajra which is a symbol of esoteric Buddhism used by the Shingon and Tendai sect. It is a physical representation of the Diamond or Thunderbolt Realm which is one of two forms of Buddhist reality. Originally an Indo-Aryan thunderbolt weapon it eventually evolved into a single, double, triple or even five pronged object. In the image to the left the vajra is the handle of a bell.

"The Buddhist vajra embodies the incisive power of wisdom to disarm hindrances to enlightenment. A five-pronged vajra, employed only by the chief officiant, is associated with five kinds of wisdom of the Five Great Dhyani Buddhas...as well as with the five elements...the five senses, and many other sets of five. A three-pronged vajra is linked to karma and its manifestations in body, speech, and mind."

Quoted from: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 1, entry by Jane T. Griffin, p. 196.

An alternate name for the kongōsho is toko. It is also known as a kongō rei (金剛霊 or こんごうれい) or ritual bell. It is also referred to as a gokorei (五鈷鈴 or ごこれい) whenever it has five prongs which generally converge at the top .

Robert Beer in his book The Encyclopedia of Tibetan Symbols and Motifs published by Shambala in Boston in 1999 (pp. 233-4) says of the vajra "As the adamantine sceptre of peaceful divinities and the indestructible weapon of wrathful deities, the vajra symbolises the male principle of method or skilful means. It is held in the right or male hand [in Tibetan iconography]. When coupled with the ghanta or bell - which symbolises wisdom and is held in the left or female hand - their pairing represents the perfect union of method and wisdom, or skilful means and discriminating awareness." 1 |

|

Kōro |

香炉

こうろ |

An incense burner. The smoke itself if referred to as kōen (香煙 or こうえん). |

|

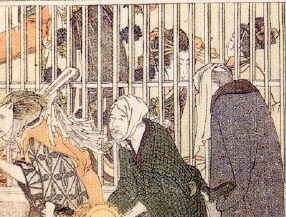

Kōshi |

格子

こうし |

Latticework - this is at the front of the house of prostitution facing the street through which the courtesans can be viewed by prospective customers. This hardly differs from a visit to the red-light district of Amsterdam in the late 1960s where the 'ladies' displayed their goods in the street level windows. Of course, these were geared toward the individual girl and not a whole bevy of beauties. Perhaps they still do that today, but haven't seen this for myself in decades. |

|

Kōshijima |

格子縞

こうしじま

|

Plaid: Plaids in Japanese prints are a special interest of mine. I have asked several questions of several scholares about their history, but have yet to get a satisfactory response. Anyone interested in Scotland (香港仔 or すこっとらんど) knows that the Scots are famous for their plaid tartans. Patterning may be natural to every culture on earth, but as best I can tell only the Scots and the Japanese raised it to the level of an art form. Question: Could the importation of Scottish patterns have influenced their development of plaids in Japan or can someone show me examples that pre-date Japanese contact with the West? Surely there is someone out there who is versed well enough with the history of Japanese textiles who could tell me the answer.

Note that benkeigōshi (弁慶格子 or べんけいごうし) and benkeijima (弁慶縞 or べんけいじま) are also words for 'plaid'. 1, 2, 3 |

|

Koshimaki |

腰巻 こしまき

|

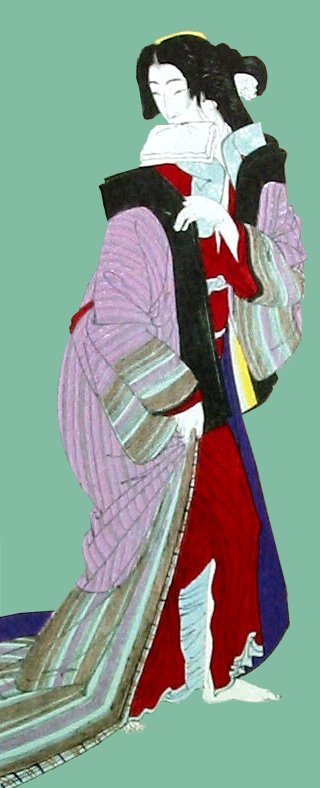

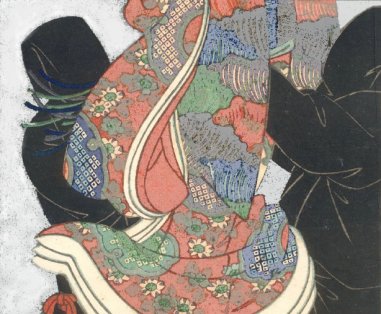

The koshimaki is an underskirt or undergarment worn beneath the kimono.

The image at the top to the left shows a beautiful woman who is probably applying her makeup. Below that is an enlarged detail of the place where her bare leg appears.

When the red koshimaki appears ruffled it is said to be reminiscent of labia. The color emphasizes that allusion.

The two top detail images to the left are from a print by Kunisada.

CONFIRMATION

In Womansword: What Japanese Words Say About Women by Kittredge Cherry published by Kodansha International in 1987 on page 26 there is an entry entitled ko itten: A Touch of Scarlet. "When a lone flower blooms brightly in the foliage, Japanese admire it for adding 'a touch of scarlet' (ko itten). The same phrase denotes one woman in a group of men."

The association with women "...seems commonsensical to the Japanese. Red is 'pretty', an attribute females are supposed to seek." It can also be the color of a happy celebration. However, it is the undergarments which are really the subject of this entry. "The undergarments worn beneath kimonos by Japanese women traditionally have been red, a color thought to ward off menstrual pain and keep the female reproductive system running smoothly. Men considered a glimps of this red underwear to be very erotic." Remember Cole Porter said "In olden days a glimpse of stocking was looked on as something shocking..." And that was said about Western society in 1934. The image to the left at the bottom is a detail from a print by Yoshitosh showing the disheveled courtesan Shiraito of the Hashimoto house published in 1886. The red undergarment is clearly visible from her right shoulder down to her feet. Take a fresh look at some of your prints or images in books or on-line when you get a chance and perhaps you will see them in a new light - that is, if you didn't already know this stuff.

Ko itten is 紅一点 or こういってん.

A clearer sense: In Kosode: 16th-19th Century Textiles from the Nomura Collection by Amanda Mayer Stinchecum it states that the koshimaki is "Literally [a] 'waist wrap'.... Worn slipped off the shoulders and held only at the waist by a separate sash." |

|

Koshimino |

腰蓑

こしみの |

A grass apron worn by cormorant (ukai) fishermen. Koshi (腰) means 'hip' and properly mino (蓑) means 'straw raincoat', but in this case a protective straw apron.

The image to the left is a detail from a print by Eisen.

See also our entries on ukai and mino. |

|

Koshinzuka |

腰蓑

こしみの

|

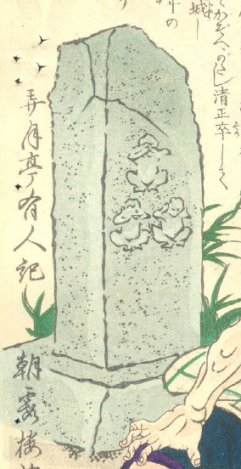

A pointed stone stele which was thought to be imbued with the spirit of a god or kami which protected travelers. Frequently carved with the image of the three monkeys.

For a full view of the whole print by Yoshiiku click on the number one in the column to the right. For more information about koshinzuka click on the number two to the right. That way you will also see the full triptych by Kunisada. 1, 2

|

|

Kote |

籠手

こて

|

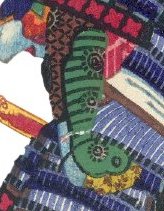

A reinforced protective sleeve worn on the forearm of a warrior. According to one informative site only the left arm was covered until the 12th century. This was done to keep the armor robe away from the bowstring. From the 12th century on the kote was worn on both arms.

It was common to decorate the sleeves with the family crest or mon.

The first character 籠 means 'basket' or 'cage' and the second character 手 means 'hand.'

The details to the left are from a print by Yoshiiku. To see the full print click on the number 1 to the right. 1

|

|

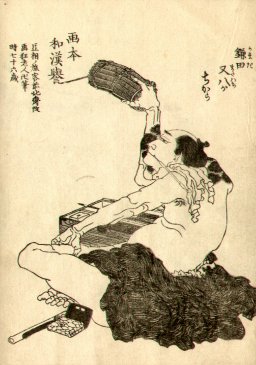

Koto |

琴

こと |

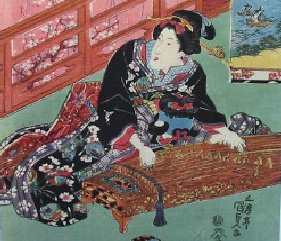

A popular Japanese zither usually made of paulownia wood with 13 strings which are plucked with small plectrums on the thumb and first two fingers of the right hand.

According to The Shogun Age Exhibition (cat. entry #254, p. 242) the "koto (also called the sō) is a musical instrument of Western origins that came to be used in China in about the eighth century, B.C. The koto used at the beginning of the Christian era had five strings, but it is thought that the change to the present-day thirteen string model occurred sometime in the fifth or sixth century, A.D." 1, 2 |

|

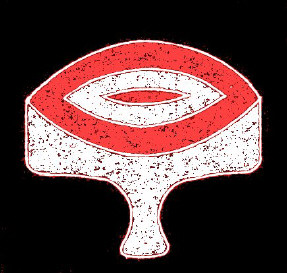

Kotoji |

琴柱

ことじ |

To the left is a family crest or mon using the bridge of the koto as the basic design. A different design motif was used for the bridge of a shamisen. |

|

Kotsuzumi |

小鼓 こつずみ |

A small hand drum |

|

Kuchinashi |

梔

くちなし

|

Gardenia jasminoides or kuchinashi: In an appendix to Roger Keyes' catalogue of the Ainsworth collection at Oberlin College dealing with Japanese colorants the authors note "...that the dyeing of cloth was a fine art when the first prints were made and, hence, the colorants used in treating cloth were likely to have been employed initially in printmaking..." That is true of this particular warm yellow dye.

Hiroshi Yoshida in his Japanese Wood-block Printing (p. 72) concurs. He notes that kuchinashi was probably used formerly, but is rarely used today. Yoshida adds "Good yellow is difficult to obtain."

Amanda Mayer Stinchecum in Kosode: 16Th-19th Century Textiles from the Nomura Collection: 16th-19th Century Textiles from the Nomura Collection (pp. 202-3) provides considerable information about this plant and its use.

A low, evergreen shrub which can be found in south-central Honshū, Shikoku and Kyūshū. While the flower is strikingly beautiful and remarkably fragrant it is the fruit pod which counts when it comes to making the dye. Harvested in the fall the seed pod contains crocin (a carotenoid). Boiled in water the end product requires no mordant. Light sensitive this dye has been used since the Nara period.

|

|

The picture of the bloom above was taken by Jon Suehiro at the Fort Worth Botanic Garden on April 29, 2006. The shot of the pods was taken by Sue Suehiro at the Botanical Gardens Faculty of Science Osaka City University (大阪市立大学付属植物園 December 7, 2003. Sue operates a large web site at http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm.

It is

well worth a

visit. An interesting tangential bit of information: In 1761 the gardenia was named in honor of Dr. Alexander Garden (1730-91). I did not know that. |

||

|

|

||

|

Kumade |

熊手

くまで |

Kumade, literally 'bear forepaw or hand'. I would like to thank our ever vigilant contributor Eikei for reminding me of this.

In 1960 U. A. Casal in his "Lore of the Japanese Fan" published in the Monumenta

Nipponica (p. 101) wrote: "Kumade, bamboo-rakes sold at certain temple

festivals and taken home to procure wealth, are behung with

Notice also the small braided rope or shimenawa strung right below the mask.

See also our entry on tori no ichi on our Tengu thru Tsuzumi index/glossary page. |

|

Kumagai Jiro Naozane |

熊 谷 次 郎 直 実 くまがい.じろう.なおざね |

Character from the play Ichinotani futaba gunki 1 |

|

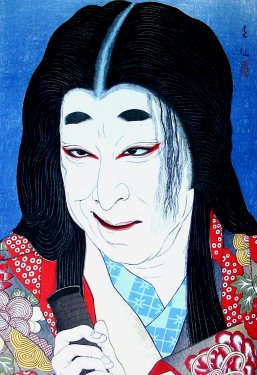

Kurai-boshi |

位星

くらいぼし |

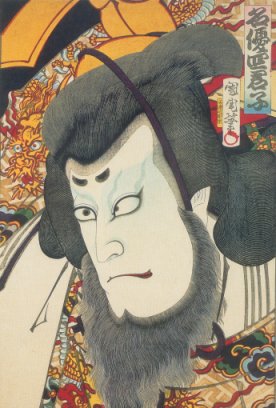

"An aristocrat's black 'stars of rank' (kurai-boshi, used only in Kabuki to denote courtly rank) painted on [the] forehead."

Quote from: The Actor's Image: Print Makers of the Katsukawa School, Timothy Clark, Osamu Ueda and Donald Jenkins, Princeton University Press, 1994, p. 207.

The image to the left shows Ichikawa Kuzō as Fujiwara Shihei dated 1894. Shihei was a 9th century court figure. |

|

Kurogo |

黒子

くろご |

Roger Keyes stated: "In kabuki, black is a non-color. The ubiquitous hooded stagehands called kurogo, or 'little black men,' who run on and off stage during performances placing and removing properties, arranging costumes, prompting, and helping with effects are theoretically invisible to the audience and seldom appear in prints. Playwrights or close relatives of the actors were often appointed to the job."

Quote from: The Theatrical World of Osaka Prints, by Roger S. Keyes and Keiko Mizushima, Philadelphi Museum of Art, 1973, p. 116.

The image Keyes was discussing was that of a Shigeharu print showing the actor Onoe Fujaku III 'glaring' at a butterfly which has landed on his left sleeve. A kurogo in the lower right is manipulating the butterfly prop on a stick. "Very few Osaka artists drew stage properties..." "Stage butterflies are dangled on lacquered poles in the theater to this day."

Ibid.

The detail to the left is from a Yoshitaki print illustrating a bunraku or puppet performance. Since I am not an expert in such things I cannot swear that the black hooded figures integral to puppetry are called kurogo, but until I find out otherwise I will use this image as an example. Click on the number one to the right to go to the Yoshitaki page for further comments. 1 |

|

Kurowatsunagi |

郭繋

くるわつなぎ |

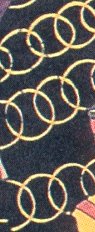

A decorative motif of interlocking rings. I have no idea exactly what this term means nor do the experts, supposedly. If I find out I will let you know later.

This image to the left is a detail from an Eizan print. |

|

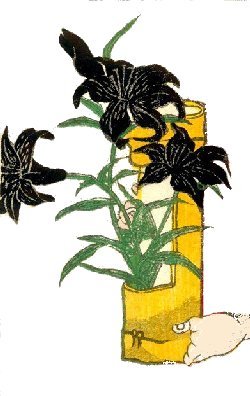

Kuro yuri |

黒百合

くろゆり

|

There is a story of a jealous lover killing the woman he loves. She comes back as a black lily. This seems to be a common motif in many cultures. Of course, it isn't always jealousy which gives us beautiful flowers. Sometimes it is an accidental event or just plain overwhelming lust. All one has to do is think of the tragic loss of Hyacinth or the self-absorption of Narcissus who was too good for any woman - or man, for that matter. 1

Quote from: The Book of Tea, by Okakura Kakuzo, Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1986, pp. 100-101.

Quote from: Chado: The Japanese Way of Tea, by Soshitsu Sen, Weatherhill/Tankosha, 1979, p. 38.

These photos are used courtesy of Shu Suehiro at http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm. It is a great site. You should visit it. Make sure you have lots of free time to do it justice. By the way, Shu says "The flowers have bad odor."

|

|

Yodogimi (1567-1615: 淀君 or よどぎみ, a concubine, was the only woman who bore Hideyoshi (1536-98) children and Nene (Kita no Mandokoro) was his wife. Above is Natori Shunsen's image of Yodogimi from 1925-29. NOTE: I haven't the slightest what the "well known" story about her, Kita no Mandokoro and the kuro yuri on Mt. Haku is. If anyone out there does know please let me in on it. Until then I will keep searching.

|

||

|

|

||

|

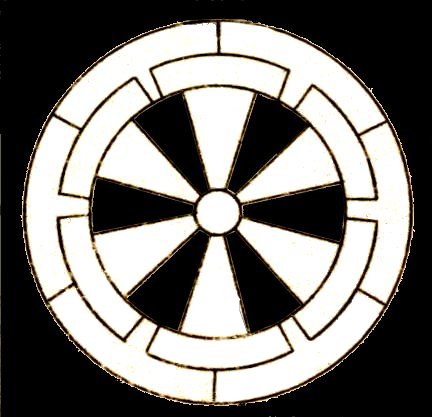

Kuruma |

車

くるま |

The wheel motif is used in several variations both for decorative effects and as a family crest or mon. One is the Buddhist sacred wheel - not shown here - and another is the Genji-guruma which is. There are also pinwheels and waterwheels. |

|

|

A thru Ankō |

|

|

Aoi thru Bl |

Bo thru Da |

De thru Gen |

Ges thru Hic |

Hil thru Hor |

|

Hos thru I |

J thru Kakure-gasa |

Kakure-mino thru Ken'yakurei |

Kesa thru Kodansha |

|

Kutsuwa thru Mok |

Mom thru N |

3.jpg) O thru Ri |

Ro thru Seigle |

Sekichiku thru Sh |

|

Si thru Tengai |

Tengu thru Tsuzumi |

|

Yakusha thru Z |

.jpg)

HOME

HOME