|

JAPANESE PRINTS A MILLION QUESTIONS TWO MILLION MYSTERIES |

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

|

Port Townsend, Washington |

|

A CLICKABLE INDEX/GLOSSARY (Hopefully this will be an ever changing and growing list.)

De Thru Gen |

|

|

The bird on the walnut on a yellow ground is being used to mark additions made in July 2008. The gold koban coin on a blue ground was used in June. The red on white kiku mon was used in May. |

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

Degatari zu, John W. Dower, Earl Ernst, Ebi, Ebisu, Ebiya, Eboshi, Edo, Edo no Hana Zukushi, E-goyomi, E-kyōdai, The Elements of Japanese Design, Ema, Emma, Engawa, John Fiorillo, Food in Japan, The Forty-seven Loyal Retainers, Fú, Fudō Myōō, Fuji, Fukiwa, Fukujusō, Fukurokuju, Fundō, Furin, Fusuma, Ga, Gagō, Gaikotsu, Gandō, Ganpi (also gampi), Ganpishi, Gassaku, Genji kuruma, Genji monogatari, Genpei and Genpei Nunobiki no Taki

出語り図, 蛯, 恵比須 or 蛭子, 海老屋, 烏帽子, 江戸, 江戸の花尽くし, 絵暦, 絵兄弟, 絵馬, 閻魔, 縁側, 四十七士, 蝠, 不動明王, 藤, 吹輪, 福寿草, 福禄寿, 分銅, 風鈴, 襖, 画, 雅号, 骸骨, 雁皮, 雁皮紙, 合作, 源氏車, 源氏物語, 源平, 源平布引瀧 and 原色浮世絵大百科事典

でがたりず, えび, えびす, えびや, えぼし, えど, etc. |

|

TERM/NAME |

KANJI/KANA |

DESCRIPTION/ DEFINITION/ CATEGORY Click on the yellow numbers to go to linked pages. |

|

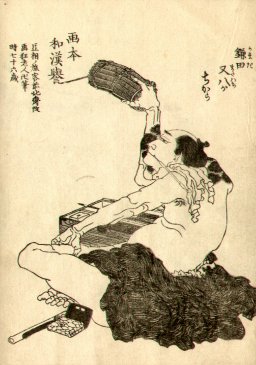

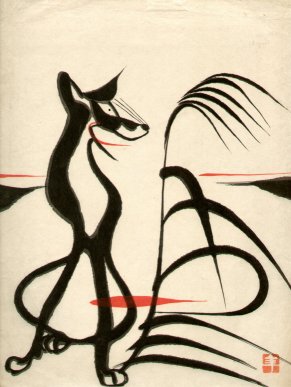

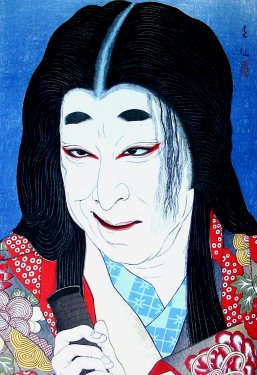

Degatari zu

|

出語り図

でがたりず |

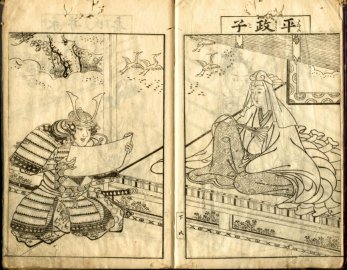

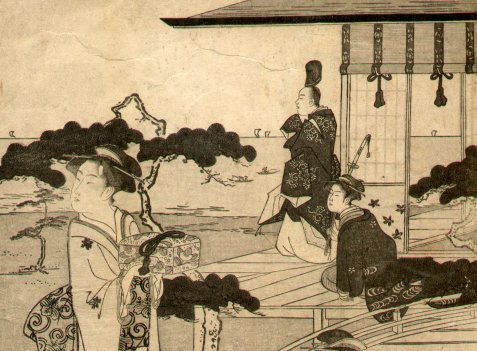

Prints which include images of the musicians who accompanied so many kabuki performances. John Fiorillo provides a wonderful commentary about this genre. He notes that the literal translation of this term is "pictures of narrators' appearance".

The use of such musicians and chanters makes sense because of the early link between kabuki and music and dance. Long before kabuki had become what we know it as today these different art forms were all parts of a whole. In time they evolved to musicians and a narrator on raised platform behind the actors.

The image to the left by Toyokuni I (Ca. 1811-14) was sent to us by our great contributor Eikei. Thanks Eikei! |

|

Dower, John W. |

|

Author of The Elements of Japanese Design 1 |

|

Earl Ernst |

|

Author of The Kabuki Theatre 1 |

|

Ebi |

蛯

えび |

Shrimp or prawn. Ebi is a word that has numerous uses in combination with many proper names such as Ebizo, an actor's name.

One thing to note is that there are quite a few variations on the kanji characters which mean ebi. These include 蝦, 海老 and 鰕.

If you are interested in seeing more information and decorative examples of this motif then click on The Many Uses of Ebi. 1 |

|

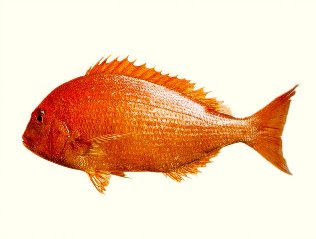

Ebisu |

恵比須 or 蛭子

えびす |

One of the Seven Lucky Gods, the Shichi-fukujin. A god of fishermen and prosperity. Of the seven he is the only one with a purely Japanese origin. His symbols are the fishing pole and the red tai, i.e., red sea bream. 1

See also our entry on hiruko, the leech child. |

|

Ebiya |

海老屋 えびや |

A Yoshiwara brothel 1 |

|

Eboshi |

烏帽子

えぼし |

A tall lacquered courtier's cap. The image to the left is one of several variations used as a family crest or mon.

Quoted from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, pp. 26-7.

Quote from: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 3, pp. 118-9, entry by Ishiyama Akira.

See also our entry on kammuri on our Kakuremino thru Kento index/glossary page.

Quotes from the glossary section of Traditional Japanese Theater: An Anthology of Plays, edited by Karen Brazell, Columbia University Press, 1998.

In one example from this book there is a photograph of an actor portraying a Shinto priest wearing an eboshi. In another an actor wears the mask of a young woman with an eboshi atop 'her' head. Variations of this type of head wear are used in Noh, puppet and kabuki.

Uesugi Kenshin is tangentially referenced on our Yoshitaki page dealing with the theme of Yaegakihime. |

|

Edo |

江戸 えど |

Former name of Tokyo. Prior to its selection by Tokugawa Ieyasu in 1603 as the location of the new base for the shogunate Edo had been only a small fishing village. In time real power emanated from Edo while the imperial capital remained in Kyoto. |

|

Quote from: "Edo Architecture and Tokugawa Law", by William H. Coaldrake, Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 36, No. 3. (Autumn, 1981), footnote 13, p. 240.

By the 15th century it was a thriving castle town or jōkamachi (城下町 or じょうかまち) under the control of Ōta Dōkan (1432-86: 太田道灌 or おおたどうかん), a vassal of the Uesugi clan in Echigo. "By 1603, the year of the official foundation of the Tokugawa bakufu and three years after the battle of Sekigahara which gave the Tokugawa national supremacy, the site of Edo had been transformed from a swampy delta with a derelict castle and a scattering of fishing and farming villages, into an embryonic capital.'' Ibid.

However, Coaldrake points out that in the long run the prohibitions had little effect. (p. 273)

Quote from: 'Sumptuary Regulation and Status in Early Tokugawa Japan’ by Donald H. Shively, Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Vol. 25, (1964 - 1965), p. 149. |

||

|

|

||

|

Edo no Hana Zukushi |

江戸の花尽くし えど.の.はなずくし |

|

|

E-goyomi |

絵暦 えごよみ |

Literally a "picture calendar" - a type of surimono. "...frequently distributed among friends to bypass government control of the issuance of official calendars as well as to serve as witty greeting cards."

Quoted from: Jewels of Japanese Printmaking: Surimono of the Bunka-Bunsei Era 1804-30 by Joan Mirviss and John Carpenter - cat. entry #13, p. 60.

"Calendar prints (egoyomi) first appeared in the early eighteenth century. They were customarily exchanged among friends at New Year, and have the numbers of the 'long' and 'short' months of the new lunar year hidden in some part of the design."

Quoted from: The Actor's Image: Print Makers of the Katsukawa School, Timothy Clark, Osamu Ueda and Donald Jenkins, Princeton University Press, 1994, p. 76, note 2. |

|

Ehon |

絵本

えほん

|

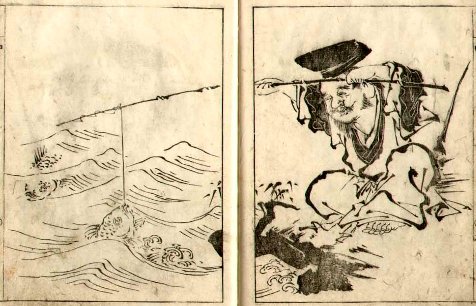

Literally "picture book": One could speak volumes about this subject, but for now I want to limit myself to two elements. The first is a general description of ehon. On the inside flap of Ehon: The Artist and the Book in Japan by Roger Keyes it states that ehon "...are part of an incomparable 1,230-year-old Japanese tradition. Created by artists and craftsmen, most ehon also feature essays, poems, or other texts written in beautiful, distinctive calligraphy. They are by nature collaborations: visual artists, calligraphers, writers, and designers join forces with papermakers, binders, block cutters and printers. The books they create are strikingly beautiful, highly charged microcosms of deep feeling, sharp intensity, and extraordinary intelligence."

The second is based on a comment Keyes made on page 140 which had always puzzled me: "Most Japanese books of this period [ca. 1800 and earlier] were printed on semi-transparent paper. Even though the sheets were printed on one side and folded in half, faint images would often show through. Most readers simply disregarded this, just as they overlooked the 'invisible' assistants dressed in black on the theater stage." (See our entry on kurogo.)

On the left are three illustrations contributed to this site by our great contributor E. The top one shows the cover of volume 2 of Settei's Onna Buyu Yoso-i Kurabe (Competition of bravery in women) of 1757. The middle and bottom ones clearly illustrate the point being made by Roger Keyes.

Thanks E!

|

|

E-kyōdai |

絵兄弟

えきょうだい

|

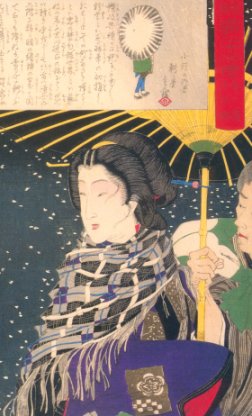

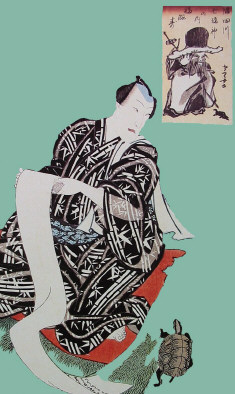

"'Sibling pictures' (e-kyōdai) are works in which a small inset picture in a cartouche resembles the main part of the design in some way, creating an interesting comparison between the two. This kind of pictorial device was already used in works by Torii Kiyonaga dating from the 1780s, but the name comes from Santō Kyōden's comic novel (kokkei-bon) E-kyōdai (Sibling Pictures), published in 1794."

Quote from: The Passionate Art of Kitagawa Utamaro, published by the British Museum Press, London, 1995, text volume, p. 181.

For years viewers have asked me what this or that cartouche means. Generally I can't tell them, but now at least I can in a small percentage of them.

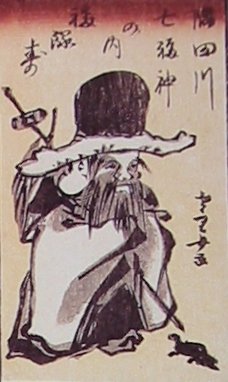

The detail from a Yoshitoshi print to the left above shows a bijin under an umbrella in a snowstorm mimicked by what may be a peasant walking away from us in the cartouche above. Below that is a detail from a Kuniyoshi print of an actor wearing a summer robe, seated on a red cloth on the grass looking down at a turtle. The cartouche in the upper right of that print shows one of the propitious gods accompanied also by a turtle. We have added an enlarged detail of that section for greater clarity. (I have doctored the original Kuniyoshi image blocking out much of the detail work so you can focus on the more pertinent elements.)

For another example in a print by Chikanobu click on the number one in the column to the right. 1

|

|

The Elements of Japanese Design: A Handbook of Family Crests, Heraldry and Symbolism |

|

This book by John W. Dower published by Weatherhill originally appeared in 1971. The image to the left is the cover of the 1991 paperback edition. Excellent volume with tons of basic information and over 2,700 illustrations. However, it is not a good guide for identifying the specific crests, i.e., mons of individual kabuki actors. 1 |

|

Ema (also euma) |

絵馬

えま (えうま) |

Today these are votive plaques given to a shrine or temple in hopes of getting one's wishes fulfilled or in thanks for a wish granted. Literally the word 'ema' means 'horse picture'. Originally horses had an ancient connection to Shinto beliefs: Horses served both as vehicles for certain gods and as messengers between the spiritual and temporal worlds. One of the functions of the ema was to end drought by bringing rain. In time the plaques displayed other hopefully propitious images, but they were still called ema. Their first known mention comes from several 11th and 12th century manuscripts and/or illustrated scrolls. In time the ema could be decorated with almost anything associated with a specific god or any human condition or endeavor. For example, if someone wanted to give up smoking, gambling or a sexual addiction the ema might include an image of a lock. Many emas were produced as wished for palliatives: Hemorrhoids relief might show a stingray; warts an octopus because in Japanese those words are homonymous; sexual dysfunction....well, I think you can guess what is shown then; etc.

Eventually larger emas were created and often showed off the skills of aspiring and established artists like several members of the Kanō school, Hanabusa Itchō, Shunshō, Hokusai, Toyokuni I and Kuniyoshi, et al.

Source: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 2, pp. 196-7, entry by Money Hickman.

The graphic to the left was contributed to our site by David Wilcox. The choice of a horse was mine. Thanks David! One note: often the symbolic image is accompanied by kanji characters, but neither David nor I felt that we were versed enough to know which terms would be the most appropriate. |

|

Emma |

閻魔

えんま |

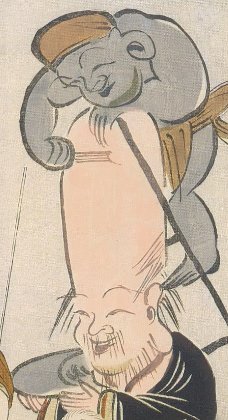

King of Hell, i.e., Jigoku in Japanese 1, 2

Quote from: Mysticism, Christian and Buddhist, by Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki, published by Forgotten Books, n.d., pp. 110-111. |

|

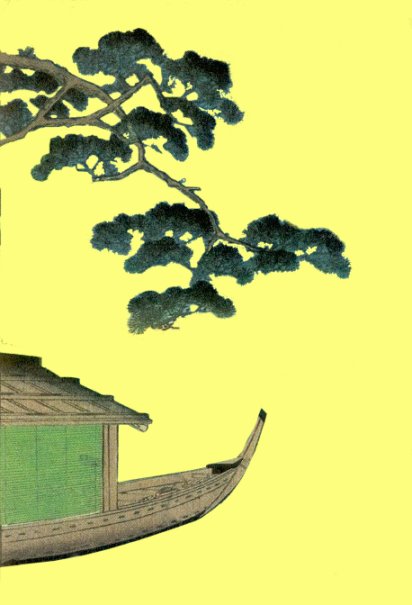

Engawa |

縁側

えんがわ

|

A veranda or porch which is protected by an overhanging eave and is generally an extension of an interior room.

The two images to the left were generously contributed to our site by E. Thanks E! Normally we only use one image, but both are so good we decided that we couldn't pass up one for the other. The top one is by Toyokuni I (豊国) and the lower one is a detail from an Eishi (栄之) print.

|

|

Fiorillo, John |

|

Excellent ukiyo-e cultural web site source 1 |

|

Food in Japan |

|

Buckwheat info and recipes 1 |

|

(The) Forty-seven Loyal Retainers |

四十七士 しじゅうしちし |

"The story of the vendetta carried out by forty-seven rōnin (masterless samurai) who remianed faithful to the memory of their former master..." |

|

Popularly known as the Chūshingura it was originally written for the puppet theater in 1748. "At the time the major Japanese dramatists were writing their plays for puppets rather than actors, a choice often attributed to dissatisfaction with the liberties that Kabuki actors often took with the texts."

Source and quotes from: Chūshingura: The Treasury of Loyal Retainers, A puppet play translated by Donald Keene, Columbia University Press, 1971, pp. ix-x.

Its full title is Kanadehon Chūshingura. "The first word means 'a copybook of kana,' a penmanship book for the writing of forty-seven symbols making up the Japanese syllabary." Written in kana, "...simple Japanese, rather than the high-flown style of the Confucian philosophers who praised the immortal forty-seven. But only pedants now use the full title of the play..."

Ibid., p. xi

For our entry on rōnin click on that highlighted word.

More extensive information will be added eventually on a page devoted to print with this theme. |

||

|

|

||

|

Fú |

蝠

ふ (But with a rising tone in Chinese unlike Japanese) |

|

|

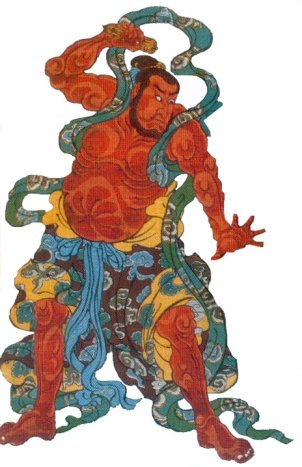

Fudō Myōō |

不動明王 ふどう.みょうおう |

Originating in the Hindu pantheon he came to be regarded as one of the five wise kings who despite his stern countenance is a saver of souls. His attributes are the sword with which he fights evil and the rope which he uses to lasso individuals who can be saved.

Anyone familiar with Fudō Myōō knows that he is always accompanied by flames. Daisetz T. Suzuki tells us why: "Acala's [the ancient Indian name for Fudō Myōō] anger burns like a fire and will not be put down until it burns up the last camp of the enemy: he will then assume his original features as the Vairocana Buddha, whose servant and manifestation he is. The Vairocana holds no sword, he is the sword itself, sitting alone with all the worlds within himself."

Quote from: Zen and Japanese Culture, Daisetz T. Suzuki, Bolingen Series LXIV, Princeton University Press, 1993, p. 90. 1 |

|

Fuji |

藤

ふじ

|

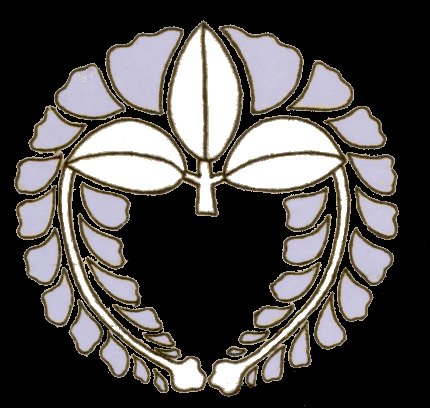

Wisteria: "Originally a wild mountain plant that twined itself around trees....was domesticated at an early date, and by the late Heian period was celebrated at parties sponsored by Japanese aristocrats. [Its]...trailing racemes of purple flowers, among the most popular of family crest and general decorative motifs..."

"The Fujiwara, whose name contains the ideograph for wisteria, was the most prominent court family in the Nara and Heian periods and had a tutelary relationship with those two religious institutions."

Quoted from: Symbols of Japan: Thematic Motifs in Art and Design, by Merrily Baird (p. 67)

|

|

Fukiwa |

吹輪

ふきわ |

An elaborate headdress worn by a princess.

Professor Samuel Leiter translates fukiwa as literally meaning "blow circle." A "...beautiful wig worn mainly by princesses (hime or himesama) in jidaimono. The large, round topknot (mage) contains a red hand drum-like ornament inserted horizontally through it, with a red bow and decorative starched paper strips (takenaga) hanging from beneath the topknot. Flower combs with silver plum blossoms and butterflies are inserted at the front."

Quoted from: New Kabuki Encyclopedia: A Revised Adaptation of kabuki jiten, compiled by Samuel L. Leiter, 1997, p. 99. 1 |

|

Fukujusō |

福寿草

ふくじゅそう

|

Literally "the grass of luck and longevity" and also referred to as the "pheasant's eye". This is the Adonis flower a symbol of the New Year and prosperity. Hokusai included it in more than one surimono.

The image to the left is a detail from a print by Yoshitoshi where a woman is trying to decide between the purchase of two different Adonis flower selections.

In Mock Joya's Things Japanese (pp. 193-4) it states that the "Fukuju-so (Adonis amurensis) has bright little golden blossoms. Its buds are silver gray, the leaves are green, but its blossoms are bright gold. Its name in Japanese means 'wealth-long-life-plant.' Because of its golden blossoms and also its lucky name, the flower is much admired by the people who use it especially for decorating their homes for the New Year celebration." This plant prospers in colder climes and is said to have originated in Hokkaido which was called Ezo-ga-shima. There is a story that says that "Once there lived in Ezo a beautiful goddess called Kunau. Her father betrothed her to the god of the earth-mole. But she did not care for the groom-elect selected by her father. Her refusal to marry the god of the earth-mole so angered her father that she was reduced to becoming a common wild blossom as punishment for disobeying her father. ¶ Thus she turned into a blossom which came to be known as Kunau or Kunau-nonnon. ¶ By the Ainu people, fukuju-so is still called Kunau. The tale of the Goddess Kunau is related by Ainu parents to their little daughters as a lesson teaching them the duty of obeying their parents. But if they were sure to be transformed into such beautiful blossoms, Ainu maidens might oppose the command of their parents to marry and follow the example of the Goddess Kunau."

These photos are shown courtesy of Shu Suehiro at http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm. |

|

Fukurokuju |

福禄寿 ふくろくじゅ |

One of the Seven Propitious Gods. He is the god of wealth and longevity. 1 |

|

Fundō |

分銅

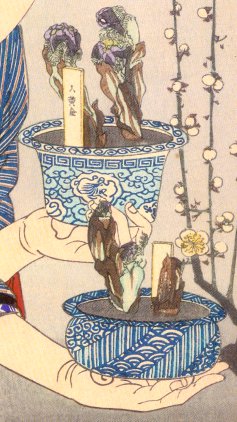

ふんどう |

A weight or counterweight: One of the symbolic lucky treasures. To the left (above) is an image of a fundō from the robe of a beautiful woman or bijin in a print by Eishō. Her kimono is covered with this and other treasure symbols. Often seen along with other treasures as decorations on ceramics, fabrics and other items. The image on the bottom left is another variation on the fundō motif - also found on an Eishō print.

|

|

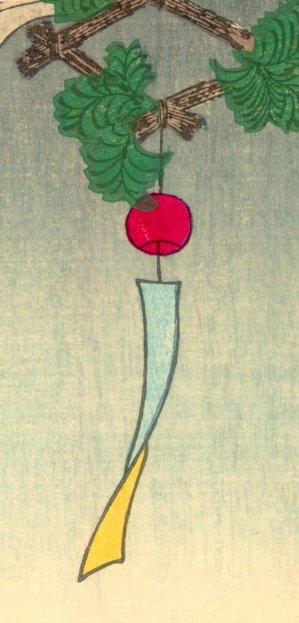

Furin |

風鈴

ふうりん |

Wind chimes which are considered a sign of summer. The two kanji characters mean 'wind' 'bell'.

The top example to the left is from a print by Toyokuni III in combination with Hiroshige. The one at the bottom is a detail from a Chikanobu print. Click on the numbers to the right to see the full prints. 1, 2

|

|

Fusuma |

襖 ふすま |

Sliding screen used as a room partition |

|

"Rooms in houses rarely have more than one solid wall.... The other sides are closed off with sliding windows and doors, which move on double runners at the top and the bottom. At the bottom is a groove level with the floor or the mats, at the top a rafter one or two ells below the ceiling so that panels can be opened up and taken away as one pleases."

Quoted from: Kaempfer's Japan: Tokugawa Culture Observed, edited and translated by Beatrice M. Bodart-Bailey, University of Hawaii Press, 1999, p. 263.

U. A. Casal in his "Lore of the Japanese Fan", Monumenta Nipponica, vol. 16, no. 1/2, 1960, p. 82 tells the story of Araki Murashige (荒木村茂 or あらきむらしげ) who is summoned for an audience with Oda Nobunaga (織田信長 or おだのぶなが), but suspects that this could be dangerous. In those days "In lordly mansions the sliding doors (fusuma) were not of paper, but of heavy, wooden panels in even heavier frames. They moved in shallow grooves, as the paper fusuma (or karakami) still do. It was just outside of the open fusuma that the vassal had to make his first kowtow which would bring his neck right above the grooves..." Suspecting that this was the moment he feared he whipped out his long metal-based war fan and held it right below his chin. Suddenly the wooden panels were propelled toward his head, but stopped short with a loud noise.

There were similar scenes akin to this loads of movies: Star Wars, Flash Gordon. Not exactly the same, but similar where the walls were closing in until the heroes figured out a way to stop their progress.

Cool as a cucumber Murashige acted as though nothing had happened. Nobunaga was so impressed he forgave him whatever it was that had angered him in the first place. Their detente didn't last forever, but that is another story. |

||

|

Ga |

画 が |

Literally this means picture or drawing, but following a signature it means "drawn by" or "did this picture." 1 |

|

Gagō (also called a gō) |

雅号 がご |

An art name. |

|

In the West we have Christian names, surnames, nicknames, noms de plume, stage names, etc., but we have nothing quite like the assortment of names the Japanese have. Not only that but they are often changed and this makes it difficult for a novice to the field to know who is who. "You can't tell the players without a scorecard."

Richard Lane, who actually calls the gō a nom de plume, notes: "Indeed, of the thirty or more alternative names that Hokusai employed during his seventy-year career, about half were passing fancies. Most were used with the previous name for some time, so as not to confuse his public..."

Quoted from: Hokusai: Life and Work, published by E. P. Dutton, 1989, p. 23.

It is interesting that a quick search on the term gagō can also mean refined diction or polite expression. Gō by itself means word or language. |

||

|

|

||

|

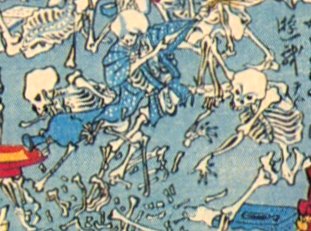

Gaikotsu |

骸骨

がいこつ |

Skeleton(s)

To the left is a detail from a print by Kyosai. |

|

Gandō |

がんどう |

A handheld lantern which directs a light very much like a flashlight does.

The image to the left is a detail from a print by Ashiyuki. To see the full print and much more info click on this link: |

|

Ganpi (also gampi) |

雁皮 がんぴ |

A rare type of paper made from the wikstroemia plant 1 |

|

Ganpishi |

雁皮紙 がんぴし |

Ganpi paper 1 |

|

Gassaku |

合作 がっさく |

A single work of art produced by two or more artists, i.e, a collaboration. In the example to the left the figures are by Toyokuni III and the flowers are by Hiroshige. There are many such examples in ukiyo prints and paintings.

There is a very informative and interesting article on this topic by Jan de Jong originally published in "Andon". Below is a link to that article in pdf form. I would encourage everyone to read this.

http://www.orandajin.com/dasite/Gassaku.pdf

|

|

Genji kuruma |

源氏車 げんじ.くるま |

A decorative pattern of interlocking wheels --- probably of an ox cart which was a traditional means of transportation for the nobility. |

|

Genji monogatari |

源氏物語 げんじ.ものがたり |

"The Tale of Genji" - Japan's first great novel written in the 11th century by Murasaki Shikibu (紫式部 or むらさきしきぶ). |

|

Genpei |

源平 げんぺい |

A term which means both the Genji and Heike clans or the two opposing sides 1 |

|

Genpei Nunobiki no Taki |

源平布引瀧 げんぺいぬのびきのたき |

Kabuki play: "The Genji and Heike at Nunobiki Waterfall" 1 |

|

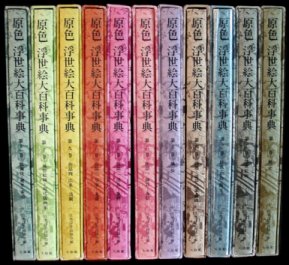

Genshoku Ukiyoe Daihyakka Jiten |

原色浮世絵大百科事典

げんしょくうきよえだい ひゃっかじてん |

An 11 volume ukiyo-e encyclopedia.

|

|

In a syllabus for an art history class at Columbia University the Genshoku Ukiyoe Daihyakka Jiten is described as "the single most important and useful reference work in this area." Abundantly illustrated it offers visually more than any other source material on ukiyo-e subject matter that I know of. The text is entirely in Japanese and although my understanding of that language is somewhere to the far side of miserable these volumes still offer me a wealth of information. (Remember: every picture is worth a thousand....) Hours of struggling often end in epiphanies.

Volume 3 alone has been invaluable. At the back of that volume are two lists unlike any others I have seen anywhere: 1) A critical listing of more than 1,000 publishers' seals - far from comprehensive, but better than anything else I have ever seen. Each illustrated entry is accompanied by detailed information about that particular publishing house. And 2) what I believe is the most extensive list of date and censor seals that can be found anywhere.

I am not uncritical of encyclopedias in general whether they are written in English or any other language, but I have to admit that they are almost always the best starting point for a research project. Anyone interested in ukiyo-e who has access to this set should seriously consider spending the time it takes to get to know it well. It is rich and you will surely reap the benefits. |

||

|

|

A thru Ankō |

|

|

Aoi thru Bl |

Bo thru Da |

Ges thru Hic |

Hil thru Hor |

Hos thru I |

|

J thru Kakure-gasa |

|

Kakure-mino thru Kento |

|

Kesa thru Kodansha |

|

Kōgai thru Kuruma |

Kutsuwa thru Mok |

Mom thru N |

O thru Ri |

Ro thru Seigle |

|

Sekichiku thru Sh |

|

Si thru Tengai |

|

Tengu thru Tsuzumi |

|

Yakusha thru Z |

3.jpg)

HOME

HOME