Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画Port Townsend, Washington |

|

A CLICKABLE INDEX/GLOSSARY

U thru Z |

|

|

The gold koban coin on a blue ground is being used to mark additions made in June 2008. |

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

Uchide no kozuchi, Uchiwa, Udon noodles, Uirō, Ukai, Ukiyo-e Prints, Ume, Unbo, United Nations General Assembly, Uri, Uroko, Usagi, Utagawa Hirosada, Utagawa Hiroshige II, Utagawa Kunisada, Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Utagawa Toyokuni I, Utagawa Yoshikazu, Rudolph Valentino Wankosoba, Waraji, Washi, James McNeill Whistler, Willow Pattern, Worcester, The World of the Meiji Print: Impressions of a New Civilization, Yagasuri, Yajirobei, Yakara no tama and Yakata-bune

打ち出の小槌, 団扇, 饂飩, 外郎, 鵜飼い, 浮絵, 浮世絵版画, 梅, 雲母, 国連総会, 瓜, 鱗, 兎, 歌川広貞, 二代広重, 歌川国貞, 歌川国芳, 歌川豊国, 歌川芳員, 輪違,

椀子蕎麦, 蕨, 草鞋, 和紙, 矢絣, 彌次郎兵衛 and

うちでのこづち, うちわ, うどん, ういろう, うかい, うきえ, うきよえ.はんがん, うめ, うんぼ, etc.

|

|

|

TERM/NAME |

KANJI/KANA |

DESCRIPTION/ DEFINITION/ CATEGORY Click on the yellow numbers to go to linked pages. |

|

Uchide no kozuchi |

打ち出の小槌 うちでのこづち |

The magic mallet carried by Daikoku, one of the Seven Propitious Gods. |

|

Uchiwa |

団扇

うちわ

|

"For the Japanese, fans are not merely for fanning...but they are quite indispensable in ceremonial, social and daily activities throughout the year.... Almost all races have had their fans...but nowhere else in the world have fans become such articles of necessity and utility in Japan."

The uchiwa, a flat fan, is one of two types of Japanese fans. The other is the ogi or folding fan.

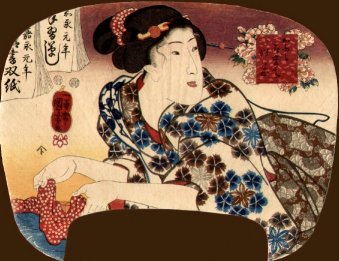

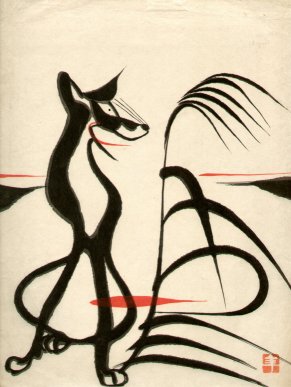

The top image to the left by Kuniyoshi is an example of a print made especially to be cut out and pasted down to the stiff panel of the uchiwa. This print was sent to us courtesy of E., our most generous contributor. The image below that is only one example of the use of a fan as a family crest or mon.

preference used by women. It is never part of one's 'dress'. It does not belong to one person in particular. It is the fan of the household, belongs to the group."

According to Casal the most popular form still used today, the Edo uchiwa (江戸団扇 or えどうちわ), was invented in 1624 by an unknown genius who realized that if you split a piece of bamboo from the node outward it would form ribs which would support paper or other materials creating a sturdy and practical fan. |

|

U. A. Casal in his "Lore of the Japanese Fan" (Monumenta Nipponica, vol. 16, no. 1/2, 1960, p. 64) notes that "The Japanese word uchiwa, for the stiff roundish fan, is evidently a corruption of utsu-ha [うつは?], the 'striking (or swatting) leaf.'" He adds that "Even today women and children use uchiwa to catch fireflies, the fan being sometimes attached to a bamboo for greater reach."

Uchiwa are also referred to as dansen (団扇 or だんせん). Note the kanji characters are the same.

Casal (p. 66): "The uchiwa became the fan of the home. Always ready at hand in summer, the first thing offered to a guest when he calls.... It never developed into a ceremonious fan, and was by preference used by women. It is never part of one's 'dress'. It does not belong to one person in particular. It is the fan of the household, belongs to the group."

According to Casal the most popular form still used today, the Edo uchiwa (江戸団扇 or えどうちわ), was invented in 1624 by an unknown genius who realized that if you split a piece of bamboo from the node outward it would form ribs which would support paper or other materials creating a sturdy and practical fan.

The Fukui district (福井県 or ふくいけん) produced uchiwa covered with paper treated with persimmon juice making them waterproof. They could then be dipped in water and fanned for greater relief in the hottest weather. These are called kaki-uchiwa (柿団扇 or かきうちわ). Some believed that just using persimmon treated fans could keep the god of poverty, Bimbō-gami (貧乏神 or びんぼうがみ), at bay. (Casal - p. 68)

Prior to modernization some firemen would climb to rooftops at some distance from a fire and would use oversized uchiwa at the fire being fought. It was meant to symbolically drive away the evil flames. (C. - p. 69)

Men would use uchiwa, but only in private. (C. - p. 70) |

||

|

|

||

|

Udon noodles |

饂飩 うどん |

In Mock Joya's Things Japanese (p. 56) there is a lament that an old method for curing colds had died out. "To make the bath cure more effective, [in] many public bathhouses.... there was a custom of ordering udon (hot wheat noodle soup) or soba (buckwheat noodles in hot soup) from neighboring noodle houses and eating it while comfortably bathing in the hot tub. Up to the middle of the Meiji ear, this custom was very popular in various cities and towns. Enjoying the warmth of the hot tub, one can leisurely eat a steaming bowl of udon or soba. The noodles taste particularly good, as the eater is in a pleasant turn of mind brought about by the warm bath. It cures the cold, but at the same time, it is liable to create a habit. Whether one has a cold or not, whenever he goes to the bathhouse, he is tempted to order a bowl of udon." 1 |

|

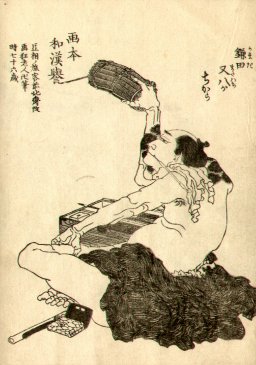

Uirō |

外郎

ういろう |

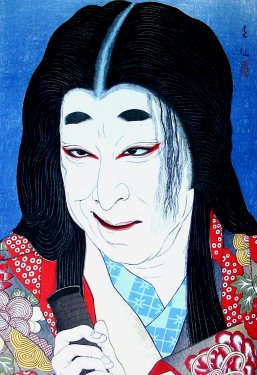

A sweet made from rice powder. However, this product was also sold as a cure-all "...a kind of panacea used as an expectorant, deodorant, and mouthwash (among other things)." We mention this because Danjūrō II created in 1718 the character of a peddler carrying a large chest on his back which holds his wares.

The image to the left is from a karuta deck of eighteen cards each representing one of the kabuki jūhachiban or the eighteen plays that became the standard vehicle of the Ichikawa family of actors.

There is an ancient universality to the tradition of snake oil salesmen preying on people searching for a panacea. While most bogus potions were rarely toxic, whether applied externally or ingested, their greatest efficacy would probably be scratched up to 'the placebo effect'.

The battle between the two camps best represented today by alternative medicine advocates on the one hand and the FDA on the other leave most of us puzzling over the proper course of action. Yet there seems to be no silver bullet although at times things like penicillin and MSG were thought to be damned close. But people keep hoping. Conclusion: As long as there are snake oil or uirō salesmen there will be a public gullible enough to buy from them. |

|

Ukai |

鵜飼い

うかい |

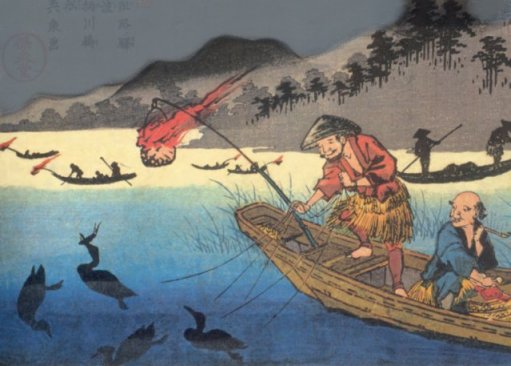

Cormorants (鵜 or う) are long necked, diving birds known for their voracious appetites. (The OED says that the word 'cormorant' can be used figuratively to describe a greedy, rapacious person.) Ukai is cormorant fishing.

The birds are captured and trained to dive on command to 'fetch' fish. A group of cormorants are tethered by a handler who pulls the birds in to remove their catch. To prevent the birds from swallowing the fish there are rings placed around their necks. |

|

This is an ancient East Asian technique not unique to Japan. While this system has been practiced on various rivers the most famous local is on the Nagara River in Gifu. Often these fishermen came under the protection of local lords, but the one on Nagaragawa was patronized by the Imperial Court. Their cormorants are trained to catch ayu (鮎 or あゆ), sweetfish or freshwater trout, which are then sent onto the Court for their pleasure.

Cormorants and god-related cormorants are mentioned several times in the Kojiki which is the oldest known Japanese text.

Source: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, p. 155.

There is a Shunshō print in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago portraying an actor in a female role as a cormorant fisherman standing on shore beside the boat holding a torch. This print dates from ca. 1771-2 and is the earliest example I have seen so far. If you know of an earlier one please contact me.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Uki-e |

浮絵

うきえ

|

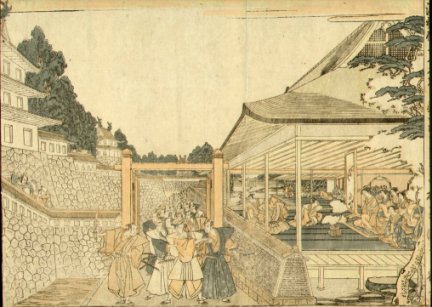

Basically a perspective print created in imitation of the European principles of recession.

"The studies of Julian Lee have shown that Japanese artists did not learn the methods of western perspective form studying western prints, but via an illustrated Chinese translation of a European treatise on perspective which was published in Canton in the early 1730s and gound its way to Edo by 1739, the date of hte first large perspective print, an interior of a kabuki theater designed by the artist Torii Kiyotada."

Quoted from: Japanese Woodblock Prints : A Catalogue of the Mary A. Ainsworth Collection, by Roger Keyes, Oberlin College, 1984, p. 94.

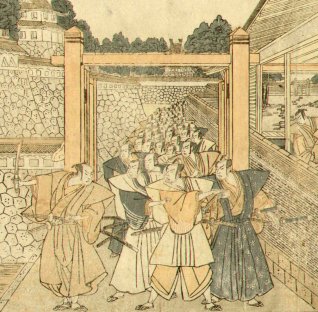

The images to the left are by Masayoshi and date from ca. 1780 illustrating a scene from the Chūshingura. This example was sent to us by our generous contributor E. Thanks E! |

|

Ukiyo-e Prints |

浮世絵版画 うきよえ.はんがん |

|

|

Ume |

梅

うめ

|

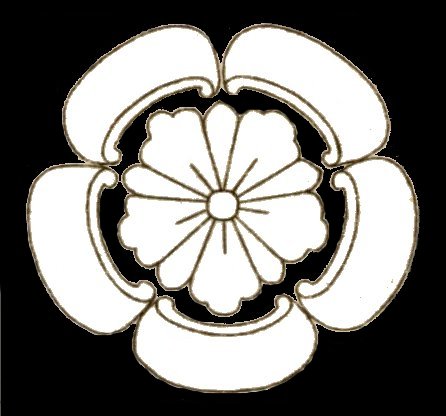

Plum blossom - This is one of most commonly used motifs for crests, i.e., mons.

Merrily Baird in her Symbols of Japan (pp. 64-65) tells us that while 'ume' is usually translated as plum it is in fact apricot. Imported from China by the 8th century it was the most frequently mentioned flower in Japanese poetry because of its qualities: A sweet perfume, delicate blossoms and because it bloomed early and endured while it was still cold enough to snow. When joined with the bamboo and the pine we have what are known as The Three Friends of Winter.

The graphic shown to the left is only one example of the 'ume' as a family crest. Baird notes that "...a guide compiled by the Matsuya Piece-Goods Store included eighty crests based on the plum blossom."

"The Song poet Lin Bu (967-1028), who is said to have surrounded himself with plum blossoms and cranes in his hermitage.... Ever since the time of Lin Bu, the cold of winter and plum blossoms blooming in the snow are considered the symbol of moral integrity and self-chosen reclusion removed from the bustle of this world, an ideal to which the Zen masters felt a deep affinity in their search for hte pure void and enlightenment."

Quote from: Zen: Masters of Meditation in Images and Writings, by Helmut Brinker and Hiroshi Kanazawa, Artibus Asiae Publishers, 1996, p. 178.

In the 15th century a Zen abbot wrote: "...spring awakening is close. / The trees do not have leaves yet; they stand amidst the melting snow. / Anticipating the [plum] blossoms is like awaiting elegant guests."

Ibid., p. 195.

The photos are being shown courtesy of Shu Suehiro at http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm. |

|

Alfred Koehn stated in his Japanese Flower Symbolism published by Lotus Court in 1939 "The Japanese see the contrast between the knotted trunks and young green shoots as symbolic of age and youth - one bent and crabbed, the other fresh and vigorous, suggesting that in spite of age, the charm and joy of youth can always rise anew."

Koehn in his article "Chinese Flower Symbolism" in the Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 8, No. 1/2, 1952, p. 127 added that "Female Chastity, also, is symbolized by the flowers on leafless branches."

According to Mock Joya the ume's position as the most beloved flower in Japan was usurped in time by the sakura or cherry blossom: "Having come to be considered as the foremost flower of the country, sakura came to be referred to as 'hana' (flower). But there was a time when 'hana' stood for ume (apricot) blossoms, as they were loved above all other flowers soon after their introduction from China.

It is not clearly known when sakura came to replace ume, but it seems that the aristocracy first came to admire sakura in the Heian period (794-1192). The Manyoshu, the oldest collection of poems which contains poems written between 315 and 759, contains no poem on sakura, but in this collection, ume has 113 poems."

Quoted from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, p. 369.

"The plant and blossoms are now generally called ume but formerly the name was pronounced 'mume.'"

Ibid., p. 377

"Cherry-viewing parties are merry, but ume parties are quiet and dignified. Probably that is the reason why the younger people have no interest in visiting ume gardens."

Ibid., pp. 377-8

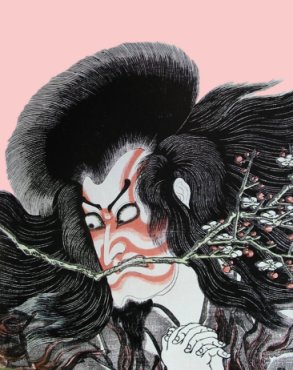

The historical figure Sugawara Michizane (菅原道真 or すがわらみちざね) who was declared the god of calligraphy and scholarship, is often associated with plum blossoms. Temples devoted to this deity known as Tenjin (天神 or てんじん) plant ume trees on their grounds. The detail of a print by Kunisada shown below portrays the actor Ichikawa Danjūrō VII as Kan Shōjō.

"Kan Shōjō, in fact, represents Sugawara Michizane (845-903)... since government regulations prohibited the use of names of real people in kabuki." Learning of his banishment from court Kan Shōjō transforms himself into the god of thunder. A branch of plum blossoms can be seen held between his clenched teeth. This "...motif [is] associated with Michizane, who before going into exile, had composed a poem to a plum tree in his garden, reminding it not to forget the arrival of spring after he was gone."

Source and quotes from: Kunisada's World, by Sebastian Izzard, Japan Society, Inc., 1993, p. 50.

Michizane was portrayed occasionally in print form riding atop an ox. Hence, if an ox is shown accompanied by plum blossoms that is a substitution for Michizane himself.

Michizane "...was fond of ume flowers from childhood, and it was for a poem on the flower written when he was 11 years old that he was first recognized by the emperor. When he was finally exiled, after a most brilliant career at Court, he wrote the following famous poem:

Kochi, fukaba nioi okoseyo ume-no hana Aruji nashitote haru na wasureso

[こちふかば によひおこせよ うめのはな あるじなしとて はるなわすれそ]

When the east wind blows, Send your fragrance, Flower of Ume. Never forget spring Even though your master is gone.

Mock Joya, pp. 580-1 |

||

|

|

||

|

unbo (or unmo) |

雲母 うんぼ (うんも) |

Mica |

|

Utamaro and Sharaku both produced prints in the 1790s which are famous for their iridescent mica grounds. "The most common method for mica backgrounds employed two identical blocks. The artisan printed an undercolor (typically black sumi for grey, safflower rose for pink, a yellow; with no undercolor the mica alone printed a silver-white ground. Then coating another identically carved block with nikawa glue or rice-starch past he printed to moisten the same background area and then sprinkled on fine mica flakes, and, finally, shook off the excess. Another method required the mica, pre-mixed with color and thinned glue, to be printed in one step; another for the image to be blocked out with a stencil and the mica in sizing applied by brush."

Source and quote from: Color Woodblock Printmaking: The Traditional Method of Ukiyo-e, by Margaret M. Kanada, Shufunotomo Co., Ltd., 1989, p. 44.

"Personally I am not very fond of mica prints, and rather dubious of the prevalent custom in the market of valuing them highly simply because mica is used in printing. Still, I cannot deny the fact that the technique of using mica was very useful in improving the art of color prints."

Quote from: The Evolution of Ukiyoé: The Artistic, economic and Social Significance of Japanese Wood-block Prints, by Sei-ichirō Takahashi, published by H. Yamagata, 1955, p. 35.

"Utamaro not only invented kira-zuri (mica-print), but improved kizuri (yellow print) and nezumi-tsubushi (grey-print), tried his hand at kabe-zuri (sand print)...." In one print a beautiful woman is looking at her reflection in a mirror which is mica printed.

Ibid., p. 41.

See also our entry on kirazuri on our Kesa thru Kuruma index/glossary page.

U. A. Casal in his "Lore of the Japanese Fan", Monumenta Nipponica, vol. 16, no. 1/2, 1960, p. 86 noted that during the Tokugawa era one advancement in the making of the folding fan was the use of three or even up to five sheets of paper were glued together with rice paste "...and umbo, or ummo, mica, probably added for stiffness." |

||

|

|

||

|

Uri |

瓜

うり |

A melon - used by many different families as their crest or mon. John W. Dower notes that during the period of feudal warfare it was common practice to behead a captured enemy combatant adding that "...medieval chronicles record an instance of a warrior who used the silhouette of a melon as a crest because this shape resembled the pool of blood which formed after he had performed this custom on the body of a particularly renowned foe."

Quoted from: The Elements of Japanese Design p. 63. |

|

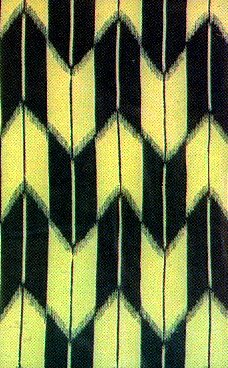

Uroko |

鱗

うろこ

|

A fish scale motif used on fabrics and other objects. According to John W. Dower this triangular fabric motif existed long before it was described as a fish scale pattern "...and its most illustrious association was with the powerful Hojo family, who ruled Japan for almost a century and a half at the beginning of the feudal period.

Quoted from: The Elements of Japanese Design p. 146.

In The Actor's Image: Print Makers of the Katsukawa School Timothy Clark notes that Musume Dōjō-ji (The Maiden at Dōjō Temple) "...has shrugged her over-kimono (uchikake) off her shoulders to reveal the triangular snake-scale pattern (uroko-gata) of the kimono, and her long hair hangs down in a wild ponytail that will whip through the air like a snake as she dances." In here bitterness over being shunned the maiden transforms into a snake. This makes more sense here than the rather limited reference to fish scaling.

Clark is writing about a Shunshō print (Cat. #62, p. 183). |

|

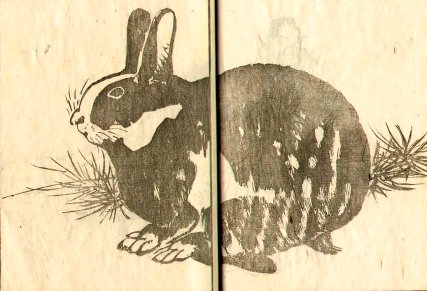

Usagi |

兎

うさぎ

|

Rabbit, hare or cony 1

|

|

Utagawa Hirosada |

歌川広貞 うたがわひろさだ |

Artist fl. 1819-65 1 |

|

Utagawa Hiroshige II |

二代広重 うたがわひろしげ |

|

|

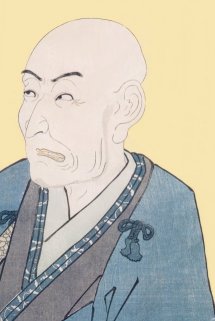

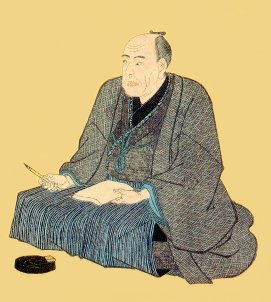

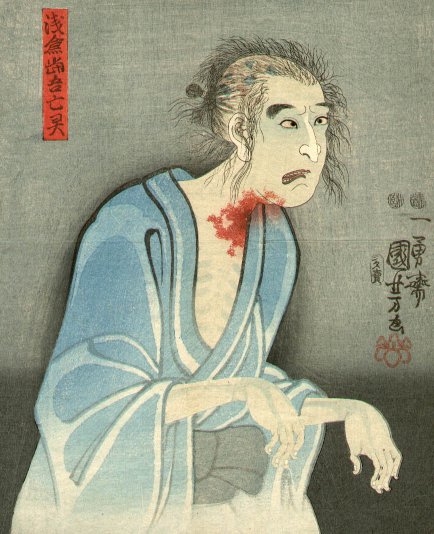

Utagawa Kunisada |

歌川国貞

うたがわくにさだ |

Artist 1786-1865.

The image to the left is a detail from a memorial print by Kunimaro. Kunisada by this time is identified by most scholars as Toyokuni III.

The odd thing about memorial portraits is that they always portray artists at the end of their careers and thus, as a rule, old men. Considering the East Asian respect for age this is not surprising. However, this seems to be just the opposite of a common practice in the West. If one were to read the obituary columns on a regular basis one would notice a pattern whereby the deaths of people in their eighties and nineties are often accompanied by photographs taken when the deceased was in their prime - often in their twenties or thirties. Somehow the Japanese memorial prints have a little more truth to them - at least from my point of view. |

|

Utagawa Kuniyoshi |

歌川国芳

うたがわくによし |

|

|

Utagawa Toyokuni I |

歌川豊国 うたがわとよくに |

Artist 1769-1825 1 |

|

Utagawa Yoshikazu |

歌川芳員 うたがわよしかず |

Artist fl. 1850 - 70 1 |

|

Valentino, Rudolph |

ルドルフ バレンティノ |

American actor, 1920s 1 |

|

Wachigai |

輪違

わちがい

|

Dower gives no clear explanation for this motif which was used in numerous variations as a mon or family crest. However, he does state: "This motif is alleged to have been abstracted from a larger overall design of a manner similar to that in which the 'seven treasures' motif... originated."

Quoted from: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, p. 133.

(See our index/glossary entry for shippō.)

|

|

Wankosoba |

椀子蕎麦 わんこそば |

Small bowls of soba with a dipping broth 1 |

|

Warabi |

蕨

わらび

|

Bracken: A crest or mon used by various families. "The new shoot of bracken that emerges in early spring is likened by teh Japanese to a fist (by the name warabide, bracken-hand). This became the basis of a fairly popular pattern used on household items, and a small number of families eventually adopted the motif as a family crest."

Quote from: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, published by Weatherhill, 1991, p. 50.

Note that there is a large number of variations of this motif some of which are hardly recognizable as being related.

In the Kodansha Encyclopedia there is an entry on the 'fern frond design' or warabidemon (蕨手紋 or わらびでもん?): "A curved-line motif ending in a tight spiral resembling a newly unfolding fern fron, used singly or in pairs back to back on artifacts of the Yayoi (ca 300 BC - ca AD 300) and Kofun (ca 300-710) periods, especially on Yayoi pottery, bronze bells... bronze weapons, bronze mirrors, haniwa (funerary sculptures), and in the painted decorations of ornamented tombs."

Quote from: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan entry by Kitamura Bunji (vol. 2, p. 252).

|

|

Waraji |

草鞋 わらじ |

Straw sandals |

|

Washi |

和紙 わし |

Japanese paper 1 |

|

Whistler, James McNeill |

ホイッスラー |

Great 19th c. painter and print maker who occasionally printed on Japanese papers. Many of his paintings show the influence of Japanese art. 1 |

|

Willow Pattern |

|

A popular 19th c. blue & white porcelain motif 1 |

|

Worcester |

ウースター |

An English porcelain factory which reproduced Asian motifs 1 |

|

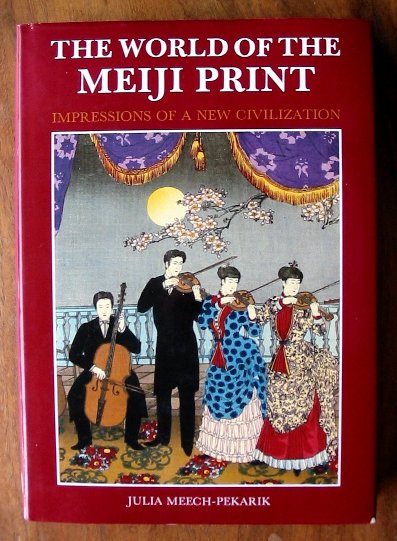

The World of the Meiji Print: Impressions of a New Civilization |

|

Like so many other specialized books this volume by Julia Meech-Pekarik and published by Weatherhill in 1986 is of use to anyone interested in Japanese culture in general. 1, 2 |

|

Yagasuri |

矢絣

やがすり |

Arrow motif for fabrics |

|

Yajirobei |

彌次郎兵衛

やじろべえ |

This is the name of one of the two comic figures of The Shank's Mare by Jippensha Ikku, It is also the name of a balancing toy as shown here. 1 |

|

Yakara no tama |

やか

|

The flaming jewel motif.

See also our entry for hōju. 1 |

|

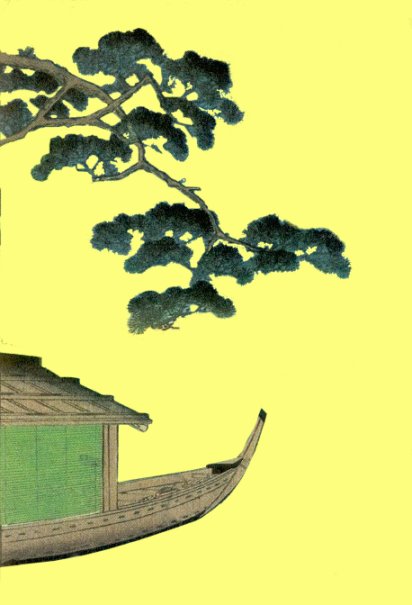

Yakata-bune |

やか

た

|

A roofed boat used for pleasure outings.

"Suzumi-bune [涼み舟 or すずみぶね] or 'cooling boats' were the most luxurious method Edo residents utilized to cool themselves in summer. Sitting on richly decorated boats and surrounded by beautiful women and many servants, they enjoyed cool breezes as their boats slowly glided down the Sumida River, while they drank sake and ate delicious food."

"The 'cooling boats' were specially constructed and were generally called yakata-bune or roofed boats. Some them were quite big, reaching a length of more than 50 to 60 feet."

Said to have begun during a particularly hot summer during the Keicho era (1596-1614). In time they became ostentatious signs of prestige and wealth and full-blown entertainment centers.

Source and quotes from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, pp. 500-1.

The image to the left is a detail from a print by Hiroshige. |

|

|

A thru Ankō |

|

|

Aoi thru Bl |

Bo thru Da |

De thru Gen |

Ges thru Hic |

Hil thru Hor |

|

Hos thru I |

|

J thru Kakure-gasa |

|

Kakure-mino thru Ken'yakurei |

|

|

Kesa thru Kodansha |

|

|

Kōgai thru Kuruma |

Kutsuwa thru Mok |

Mom thru N |

3.jpg) O thru Ri |

Ro thru Seigle |

Sekichiku thru Sh |

Si thru Tengai |

Tengu thru Tsuzumi |

Yakusha thru Z |

HOME

HOME