Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画Port Townsend, Washington |

|

A CLICKABLE INDEX/GLOSSARY

Yakusha thru Z |

|

|

The bird on the walnut on a yellow ground is being used to mark additions made in July 2008. The gold koban coin on a blue ground was used in June. |

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

Yakusha hyōbanki, Yamaboko, Yamazakura, Yamabuki, Yamaguchiya Tobei (Kinkodo), Yanagi no mayu, Yang Gui-fei, Yari, Yashima Gakutei, Yasuo Kume, Yōkai, Yōkai Attack: The Japanese Monster Survival Guide, Yomogi-soba,Yōshi, Yoshisato, Yoshiwara, Yoshiwara: The Glittering World of the Japanese Courtesan, Yotsude-ami, Yotsume, Yüan (dynasty), Yuiwata, Yukata, Yuki, Yukimi dōrō, Yukiwa, Yumiya, Zakuro, Zangiri-mono, Zarusoba, Zori, Zuishin and Zukushi

役者評判記, 山鉾, 山吹, 山姥, 山姥物, 山桜, 柳の眉, 楊貴妃, 槍, 八島岳亭, 妖怪, 洋紅, 蓬蕎麦, 養子, 芳里, 吉原, 四つ手網, 四つ目, 元(朝), 浴衣, 雪, 雪見灯籠, etc.

|

|

|

TERM/NAME |

KANJI/KANA |

DESCRIPTION/ DEFINITION/ CATEGORY Click on the yellow numbers to go to linked pages. |

|

Yakusha hyōbanki |

役者評判記 やくしゃ.ひょうばんき |

Annual actor critiques in printed form which appeared until c. 1890. |

|

Originally courtesans were rated on an annual basis and it was not a great leap to start doing so for actors too. The first such publications paid emphasis on the homoerotic allures of young male actors, but eventually covered the full range of actors. Samuel L. Leiter notes: "The contents of such books were likely to include descriptions of he actors' appearance, disposition, dancing ability, vocal quality, partying tastes, sexual proclivities, and so on, including examples of the actors' poetry and pictures of them and their mon [or crest].

This description sounds sneakily like the classified ads placed in the mostly 'adults only' alternative publications and on-line solicitations.

Leiter added: "In the early days the actors' looks and sex appeal were given more importance than their talents." I might add, that little has changed today. Many contemporary actors have better bodies and looks than skills and depth. But everyone knows that.

Quotes from: New Kabuki Encyclopedia: A Revised Adaptation of kabuki jiten, 1997, p. 696.

Regis Allegre at Kabuki21 gives the last date for such books as 1890 while Leiter gives their terminus ante quem as 1877. |

||

|

|

||

|

Yamaboko |

山鉾

やまぼこ

|

A festival float. Also, referred to as hikiyama (曳山 or ひきやま) or festival floats. Members of a neighborhood association "who are in good physical condition are assigned by a steering committee made up of representatives of the older wealthier families in the community to build festival wagons (hikiyama). To be considered 'alive' or funciotning, a wagon requires two leaders, two traffic negotiators, abundant decorations, and a continuous source of music. The hikiyama often carries structures upon which a yorishiro, or place suitable for a deity to alight is built. This usually takes the form of a mountain (yama) sculpted of papier-mâché. It is deemed an appropriate 'god-seat' since mountains, particularly impressive mountains, have been considered holy since earliest times. It is thought that in Japan 'sacred mountains' were originally designated as such because of their significance as sources of water for the surrounding farmland."

Quote from: :Matsuri: Japanese Festival Arts, by Gloria Granz Gonick, UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History, 2002, p. 45.

Right after I posted this entry I wrote to one of our great contributors to see if he had any print images of yamaboko. He didn't, but he did have these photos. Brilliant!, aren't they? The top one shows a detail of the float itself. Brilliant!

|

|

Yamabuki |

山吹

やまぶき

|

Yamabuki or Japanese Rose is also known under the botanical name Kerria japonica.

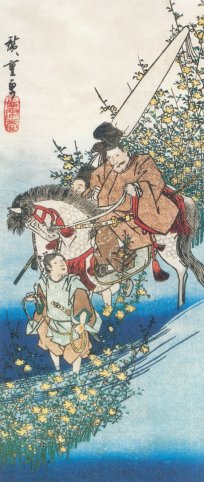

In the catalogue to the great Utamaro exhibition at the British Museum Timothy Clark describes a courtesan arranging a flowering kerria branch and notes "This is an oblique reference to the most common pictorial representation of the Ide Jewel River, which was a courtier crossing the river on horseback, with kerria blooming at the water's edge."

Quote from: The Passionate Art of Kitagawa Utamaro, published by the British Museum Press, London, 1995, text volume, p. 117.

The detail of the image with the rider is by Hiroshige shows the poet Fujiwara no Shunzei (1114-1204) crossing the Ide Tama River inspired to write a poem about the yamabuki flowers clustered there.

こまとめてなを水かはんやまぶきの

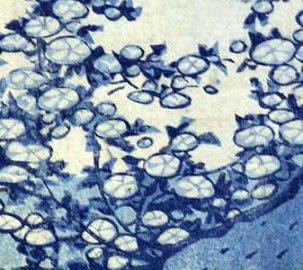

花のつゆそふ井での玉河 The image below that is a detail from a print by Kunisada. In the foreground is an actor. Behind him is an aizuri-e landscape with a relatively subtle reference to the crossing of the Ide Tama River. Here, of course, the flowers are printed all in blue, but the connection is clear. I want to thank my great friend Mike for sending me this image. 1

|

|

Yamauba |

山姥

やまうば

|

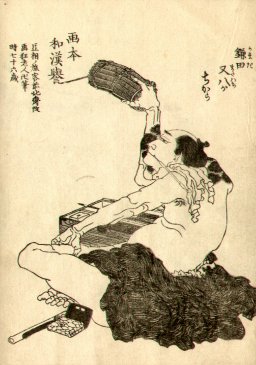

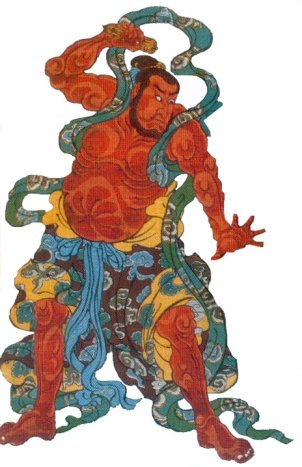

"Yamauba

was originally a female flesh-eating ogre who lived deep in the mountains,

but in the Edo period she was transformed into the mother or wet-nurse of

the strong boy Kintarō (Kidō-maru), who grew up to be the warrior hero

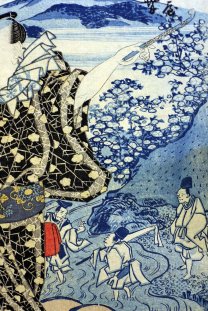

Sakata Kintoki, one of the four great retainers of Minamoto no Yorimitsu." Quote from: Demon of Painting: The Art of Kawanabe Kyōsai, by Timothy Clark, British Museum Press, 1993, p. 105. The top example to the left is a detail from a print by Kuniyoshi showing Yamauba in them more romantic mode of the Edo period. The one in the center is from a book illustration where she is shown as a truly frightening had. The Utamaro at the bottom portrays her as the doting mother.

|

|

Yamauba mono |

山姥物 やまうばもの |

"Mountain hag

play": "'Yamauba pieces' is the name given to the lineage of Kabuki dances

deriving from the concluding scene of Chikimatsu Monzaemon's puppet play

Komachi Yomamba." This genre became a motif in print form for the

expression of love of a mother for a child. Quote from: The Passionate Art of Kitagawa Utamaro, published by the British Museum Press, London, 1995, text volume, p. 224. Chikimatsu's Yamauba "...appears as a wild old woman with long hair and ragged clothes who dances opposite the infant Kintarō." Quote from: Quote from: Demon of Painting: The Art of Kawanabe Kyōsai, by Timothy Clark, British Museum Press, 1993, p. 105. |

|

Yamazakura |

山桜

やまざくら |

One of several woods used to print woodblocks, but this was the most common and popular one of the ukiyo period. Referred to as the wild mountain cherry tree or Prunus serrulata in the West. 1 |

|

Yanagi |

柳

やなぎ

|

Willow tree: In an article entitled "Chinese Flower Symbolism" by Alfred Koehn in the Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 8, No. 1/2, 1952, p. 131 it states: "As a symbol of Spring and Meekness, the Willow has inspired poets and painters; they are fond of using it as an emblem of Femininity. Popular belief holds that the Willow exercises power over evil spirits. Tombs are swept with it, and its branches are fixed to the gates of houses as an omen of Good Luck."

Merrily Baird (Symbols of Japan, p. 66) adds that the Chinese also believed that it could prevent blindness and purify. Baird notes that in Japan that yanagi "...is commonly represented with water, snow, swallows, or herons. A branch of willow (yoshi) is one of the attributes of Buddhist deity Senju Kannon [観音 or かんのん] (Thousand-Armed Kannon), who is said to use the branch to sprinkle the nectar of life contained in a vase."

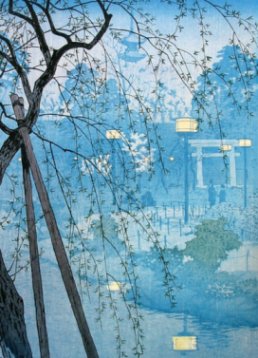

The top two photos were graciously supplied by Shu Suehiro at http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm. The bluish print detail is from a work by Kasamatsu Shirō (1898-1991: 笠松紫浪 or かさまつ.しろう). The title is given as "Evening Rain at Shinobazu Pond" (夜雨不忍池 or やうしのばずのいけ) from 1932.

Koehn in his Japanese Flower-Symbolism from 1939 noted that the display of a willow branch which has been twisted to form a circle somewhere along the branch at a farewell gathering was meant to convey "...wishes for a safe return."

In China the custom was different, but its similarities seem clear. "Willow branches were commonly snapped when parting form a firend, 'willow' (liu) being homophonous with 'stay' (liu). Since officers in Chang-an were constantly being sent off in military service or to civil posts in the provinces, the willows by the royal moat tended to have more snapped branches than most."

Quote from: An Anthology of Chinese Literature: Beginnings to 1911, edited and translated by Stephen Owen, W. W. Norton & Company, 1996, footnote, p. 394. |

|

Mock Joya adds much to our knowledge of willow lore. A 'willow waste' described a graceful, slender woman.

On New Year's Day "...the Emperor would exclaim: 'Under the yuzu [柚 or ゆず] (citron) tree? to which the Empress replied 'Medetashi' (happy)." Since the yuzu was a royal prerogative commoners substituted the yanagi for this ritual. "It is probably that from this ancient custom of using this happy expression on New Year's day, chopsticks made of willow wood are still used during New Year celebrations even today." These chopsticks are used exclusively and burned afterwards."

Source: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, p. 378-9.

Years ago I was told or I read that the weeping willow was a symbol of prostitution in ancient China. I have been unable to confirm this and have had experts I respect disagree with me. Supposedly brothels - both legal and illegal - prospered along waterways where this type of tree was commonly seen. In 1589 one of Hideyoshi's retainers opened the first licensed district in Kyoto. At the entrance to this district were two huge willow trees. It was called Yanagi-no-baba, but came to be called Yanagimachi (柳町 or やなぎまち) or "Willow Street". There was another Yanagimachi in Edo, J. E. de Becker this one "...did not derive its title from the one in the Western city."

Source and quote from: Yoshiwara: The Nightless City, by J. E. de Becker, Frederick Publications, 1960, p. 2.

The references below all come from an article entitled "Kung Hsien's Self-Portrait in Willows, with Notes on the Willow in Chinese Painting and Literature" by Jerome Silbergeld published in Artibus Asiae in 1980 (Vol. 42, No. 1, pp. 5-38).

As early as the Han dynasty (206 B.C. to 220 A.D.) in China the willow was used "...as a metaphor for feminine beauty, romantic and often erotic."

By the T'ang dynasty (618 to 970) the elegant willow was being compared to a woman's slender waist. Later Po Chü-i wrote about Ming-huang's yearning for Yang Kuei-fei. Here a woman's eyebrows are likened to the willow. (See our entry for yanagi no mayu below. Clearly the Japanese borrowed this Chinese model.)

Home again, the pools and gardens were all just as before- The hibiscus of the T'ai-i Pool, the Wei-yang Palace willows. But the hibiscus were like her face, the willows like her eyebrows, And facing them, what could he do but cry.

Even the drooping branches came to be compared with the delicate gossamer clothing of a beauty. In the anthology "Three Hundred T'ang Poems" the willow is mentioned more than any other plant. In the capital cities of Lo-yang and Ch'ang-an famous courtesans and great beauties adopted surnames meaning Willow or if not that nicknames using the same references. "The nation's finest gay quarters were in Ch'ang-an, and one of them must have been a willow-lined district known as the Chang-t'ai or Chang Terrace. The phrase "Chang-t'ai Willow," used in reference to these courtesans..." One famous poet wrote about his lover, 'the Willow of Ch'ang Terrace', who fled in turbulent times to a nunnery only to be abducted by an enemy general. The poet wrote of her:

Is the fresh green of former days still there? No, even if the long branches are drooping as before, Someone else's hand must have plucked them now!

"Willow Village, Flower Street" became synonymous with any brothel district anywhere. In Mathew's Chinese English Dictionary (p.589) a willow lane was a reference to brothels. And the expression "sleeping in the flowers, lying among willows" [is] simply translated as "passing the nights in the brothels..."

In footnote 66 Silbergeld notes other attributes ascribed to the willow by the Chinese, but not mentioned in the poetry of Kung Hsien: "...namely their common use as an herb of healing (containing a natural form of aspirin), as a ritual object in Buddhist purifi- cation rites, as a charm for warding off evil spirits, and as an aid in spirit-conjuring..."

One Confucian scholar likened a fondness for willows with dissipation and decline. |

||

|

|

||

|

Yanagi no mayu |

柳の眉 やなぎのまゆ |

Willow eyebrows - a metaphor for a beautiful woman.

Source: Jewels of Japanese Printmaking: Surimono of the Bunka-Bunsei Era 1804-30 by Joan Mirviss and John Carpenter - cat. entry #16, p. 64. |

|

Yang Gui-fei |

楊貴妃

ようきひ

|

Great beauty (719-56) who was the love object, i.e., main squeeze, heart throb, honey pie, of the T'ang dynasty emperor Xuan Zong. Romantic tales of this tragic love affair blame the collapse his empire on the emperor's neglect of his duties. Similar to the misconception that Rome burned while Nero fiddled here it is Xuan Zong's obsessive infatuation with Yang Gui-fei which leads to disaster.

Prior to modern historiography the general focus of historical events was placed on individuals rather than the larger paradigms such as economics, etc.

|

|

Murasaki Shikibu, the author of "The Tale of Genji" was born in 978? at a time when it only made sense to look at personalities as the movers and shakers. We know that she was educated and must have been well versed in Chinese literature. At the very beginning of "The Tale of Genji", Kiritsubo (The Paulownia Pavilion), makes this eminently clear. The Japanese emperor falls in love with and dotes on a minor court beauty.

"From this sad spectacle the senior nobles and privy gentlemen [of the Japanese emperor's court] could avert their eyes. Such things had led to disorder and ruin even in China, they said, and as discontent spread through the realm, the example of Yōkihi [Yang Gui-fei's Japanese name] came more and more to mind, with many a painful consequence for the lady herself, yet she trusted in his gracious and unexampled affection and remained at court.... His majesty must have had a deep bond with her in past lives as well, for she gave him a wonderfully handsome son [Genji]."

Quote from: The Tale of Genji, by Murasaki Shikibu, translated by Royall Tyler, published by Viking, 2001, vol. 1., p. 3.

In all of the versions

of the story of Yang Gui-fei the Chinese emperor's concubine has to die to

save the state. Whereas the analogy is not one to one Genji's mother dies

young and the emperor's grief is inconsolable. He neglects almost

everything, but his loss. Murasaki Shikibu's erudition is made clear in her

allusion to the Chinese poem, "A Song of Unending Sorrow", by

Bai Juyi's (772-846). In it Xuan Zong sends a Taoist priest to find the

soul of Yang Gui-fei. The priest returns with a message declaring that long

after the earth and the heavens cease to exist the lovers' grief will be

eternal. [

The story of Yang Gui-fei would have been a favorite theme in the arts of the love-loving Japanese based on Bai Juyi's poem alone, but the inclusion of this theme at the beginning of "The Tale of Genji" must have cinched its place as a Japanese motif.

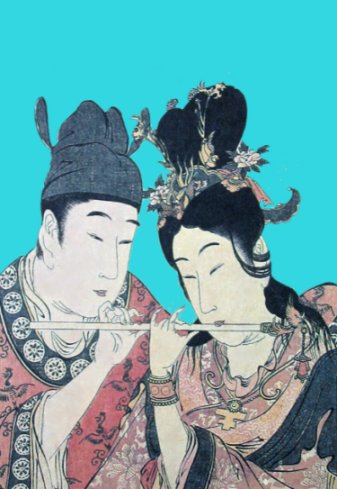

The doctored and cropped images to the left are from a print by Toyokuni I [top] and Utamaro. Note that in the bottom one both the Chinese emperor and his lover are playing on the same flute.

One other note: T'ang dynasty and later Chinese renditions of Yang Gui-fei show a full-bodied, size 16-18, Rubensesque woman. The Japanese images are generally much more svelte.

During the Ming dynasty the artist and connoisseur Wên Chên-hêng created the earliest fully extant guide for the "Calendar for the displaying of scrolls". It starts at New Year's morning when he suggest the hanging of Sung dynasty paintings of the Gods of Happiness or images of the Sages of old. "On the eighth day of the fourth month, the birthday of Buddha, you shold display representations of Buddha by Sung and Yüan artists, or Buddhist pictures woven in silk dating from the Sung period." And so it goes from event to event until "the eleventh moon [when] there should be paintings of snow landscapes, winter plum trees, water lilies, Yang Kuei-fei indulging in wine, and suchlike pictures."

Source and quote from one of my favorite books: Chinese Pictorial Art, by R. H. van Gulik, Hacker Art Books, 1981, pp. 4 & 5. |

||

|

|

||

|

Yari |

槍

やり |

Spear: According to the Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan (vol. 1, p. 89, entry by Ogasawara Nobuo) "There are two types of Japanese spears, identical in function: the hoko and the yari." The distinction between the two was based on how the spearhead was attached to the wooden shaft (vol. 7, p. 224, entry by Tomiki Kenji).

The yari came into common use in the 14th century. The Mongols had used this type of spear during their attempted invasions of Japan in the 13th century. "The yari commonly has a double-edged blade or head ranging in size from ...12 to 29 [inches]..." generally. There are several variations on the design including forked spearheads with two or more prongs.

The image to the left is a detail from a book illustration by Yoshitoshi. |

|

Yashima Gakutei |

八島岳亭 やしま.がくてい |

Artist (1786? - 1868) |

|

Yasuo Kume |

|

Author of Tesuki Washi Shuho: Fine Handmade Papers of Japan 1 |

|

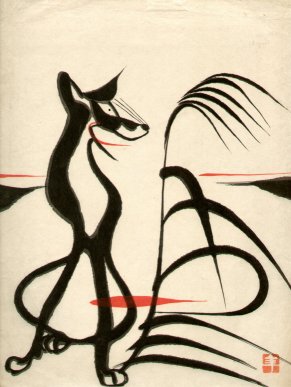

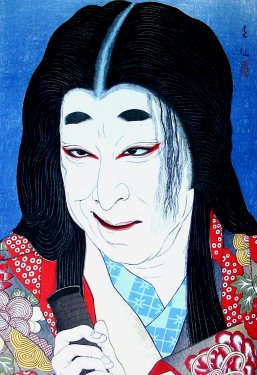

Yōkai |

妖怪

ようかい |

A ghost, demon, monster, goblin or spectre.

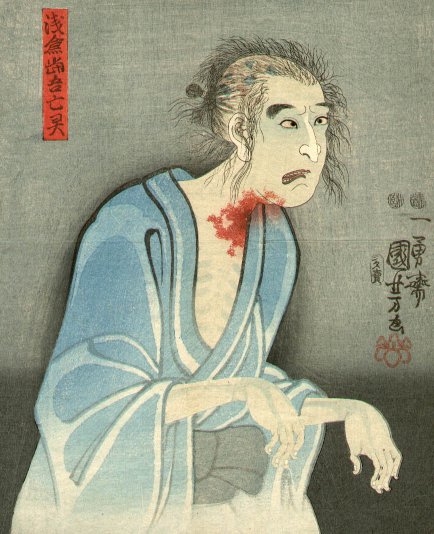

The image to the left of the bloody ghost is a detail from a print by Kuniyoshi and was sent to us courtesy of E. - one of our favorite correspondents. Creepy isn't it. In a larger detail you could see the disgusting sores on the scalp of the ghost. Maybe later. By the way, in the full sized print the ghost appears to float through the air just like the poltergeist in their eponymous movie.

The figure represents Ichikawa Kodanji IV as a Ghost of Sakura Sogorō. |

|

Yōkai Attack: The Japanese Monster Survival Guide |

|

A wonderful new book - published by Kodansha in 2008 - by Matthew Alt and Hiroko Yoda. It is by far the best book I know of in English that identifies the largest variety of traditional Japanese monsters and gives a scholarly, but fun bit of information about each of them. I would recommend that believers and non-believers alike add this to their library. You can never be too careful, what? |

|

Yōkō |

洋紅 ようこう |

Carmine red: "This was a cheap carmine from Europe used in later prints."

Quote from: Japanese Woodblock Printing, by Rebecca Salter, University of Hawai'i Press, 2001, p. 28.

Yō (洋) means 'Western', 'European' or 'foreign' and kō (紅) means 'crimson'.

When using the kyōgō or keyblock prints for the cutting of the separate blocks used in the final printing Hiroshi Yoshida wrote that he liked to use yōkō to mark particular areas by drawing lines across the area to be printed. |

|

Yomogi-soba |

蓬蕎麦 よもぎそば |

Soba made with mugwort 1 |

|

Yōshi |

養子 ようし |

Adoption |

|

Until modern times, i.e., since the Meiji Restoration in 1868, adoption in Japan was unlike anything we know of in Western terms. Practiced for more than 1,300 years it may have begun as a way of leaving a 'family' relative to honor the spirits of the deceased ancestors. At one point it was a vehicle for increasing family wealth among members of the court. Once a young man reached 15, the age of majority, the father could apply for a stipend to be paid in rice or land. If the father had a natural born son who was still a minor he could speed the process up by adopting another, but older young man and make him his son. That young man, in turn, could adopt the younger brother and when he reached 15 apply for a another stipend.

In fact, there were many different types of adoption and many different reasons for them. For example, if a family was fond of a daughter and wanted to keep her in the household they would adopt a son who would then marry her. As a result the daughter might have more power within the family and more of the its wealth would stay in the home. Or, if a family had a lot of children they might allow one of the childless friends to adopt one of theirs. Not only did adoption mean a continuation of a family line, but it also could provide positive political and economic links. There was another consequence of adoption because of a common practice by Edo times: Wealth was only passed on to the eldest son and was not divided among the remaining relatives.

However, it is the issue of

adoption when it comes to craftsmen and artists that really matters here.

Anyone who has studied ukiyo printmakers and painters will have noticed how

many of these were adopted by their teachers/masters

Sources: 1) Mock Joya's Things Japanese; 2) Things Japanese: Being Notes on Various Subjects Connected with Japan by Basil Hall Chamberlain; 3) Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan; 4) New Kabuki Encyclopedia: A Revised Adaptation of Kabuki Jiten by Samuel L. Leiter |

||

|

|

||

|

Yoshisato |

芳里 よしさと |

Pupil --- unlisted in Roberts --- of Kuniyoshi who created the inset in one of the prints from the series "Sixty Odd Provinces of Japan - Dramatic Chapters" |

|

Yoshiwara |

吉原 よしわら |

Famous Edo red light district 1 |

|

There is no better example of the Japanese homophonous penchant for ratcheting up the meaning of a word or term than that of the name of the Yoshiwara. In 1617 the Tokugawa shogunate granted a license to Shōji Jin'emon (1576-1644: 庄司甚右衛門 or しょうじ.じんえもん) for the establishment of specialized district in Edo. It had taken the government almost 6 years before it approved the original petition submitted by Jin'emon, but when they did they specified the location and the ground rules. "...the place was one vast swamp overrun with weeds and rushes, so Shōji Jin'emon set about clearing the Fukiya-machi, reclaiming and filling in the ground, and building an enclosure thereon. Owing to the number of rushes which had grown thereabout the place was re-named Yoshi-wara (葭原 = Rush-moor) but this was afterwards changed to Yoshi-wara ( 吉原 = Moor of Good luck) in order to give the locality an auspicious name." Filling in and leveling the ground, laying out the streets and building construction took ten years to complete.

Source and quote from: Yoshiwara: The Nightless City, by J. E. De Becker, Frederick Publications, pp. 3-7.

Along with the license came a set of rules set down by the governor of the district: 1) Brothel-keeping was restricted to this particular location and "...in future no request for the attendance of a courtesan at a place outside the limits of the enclosure shall be complied with."; 2) "No guest shall remain in a brothel for more than twenty-four hours."; 3) "Prostitutes are forbidden to wear clothes with gold and silver embroidery on them; they are to wear ordinary dyed stuffs."; 4) Brothels were told not to build ostentatiously and residents of the districts were to function like the citizens of other districts. For example, Yoshiwara firemen were subject to the same rules of firemen elsewhere in the city; 5) Each visitor to a brothel is to be questioned and scrutinized. "...in case any suspicious individual appears..." the governors office must be notified. There was to be no exceptions whether the visitor is a "gentleman or a commoner..."; "The above instructions are to be strictly observed."

Ibid., pp. 5-6

The original or 'Old Yoshiwara' was ordered to move to a new location in 1657 after a major fire and hence was renamed the 'Shin' or 'New Yoshiwara'. This is the pleasure quarter we know so well from the prints of the ukiyo. [Note that large urban fires have not been rare in historical Japan. However, before the modern age this was a threat common to all large cities: London burned down in 1666.]

The Yoshiwara should not be thought of strictly as a place where men went for sex. It had a remarkably subtle and profound effect on Japanese culture. "It would be a mistake to think of the Yoshiwara as a simple collection of brothels; rather, it was a highly stratified and complex world in itself that provided the means for a very sophisticated level of entertainment. New genres of music, art and literature developed around it...

Many scholars have pointed out that... quarters like the Yoshiwara provided the one institutionalized escape from social repression and control. That is the social rank of warrior, farmer, artisan and merchant (shi-nō-kō-shō), which dictated how a person lived, married, worked, and dressed, were of secondary importance to the main key for enjoying oneself in Yoshiwara - namely money."

Quoted from: 'Yoshiwara', Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 8, pp. 349-50. This entry was written by Liza Crihfield. |

||

|

|

||

|

Yoshiwara: The Glittering World of the Japanese Courtesan |

|

|

|

Yotsude-ami |

四つ手網

よつであみ |

Four-cornered scoop fishing net 1 |

|

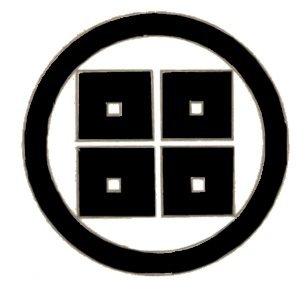

Yotsume |

四つ目

よつめ |

A mon or crest which includes variations of four boxes grouped together. However, unlike most other mons I haven't a clue about it significance other than decorative and distinctive.

Even inexplicable crests are ready tools for scholars. Timothy Clark noted this in describing the background to a triptych by Utamaro: "The crest of four squares...inside a circle on the steaming boxes [seirō - 蒸籠 or せいろ] is that of the cake shop of Takamura Ise (Yorozuya Ihei) located in Edo-chō 2-chōme in Yoshiwara. The type of cakes known as monaka no tsuki [最中の月 or もなかのつき] from this store were famous."

Quote from: The Passionate Art of Kitagawa Utamaro, published by the British Museum Press, London, 1995, text volume, p. 153 |

|

Yüan (dynasty) |

元(朝) |

Name of the 13th c. Mongol rulers of China 1 |

|

Yuiwata |

結綿

ゆいわた

|

A bundle of silk floss: This was the personal crest or mon used by several actors performing under the name Segawa Kikunojō.

The detail from a Bunchō print to the left (bottom) shows the crest prominently displayed on the robe of Segawa Kikunojō II from ca. 1770. This detail is shown courtesy of Kabuki21, the best site of its kind on the Internet. I urge that you visit it - long and often.

This motif can also be referred to as simply wata (綿 or わた).

|

|

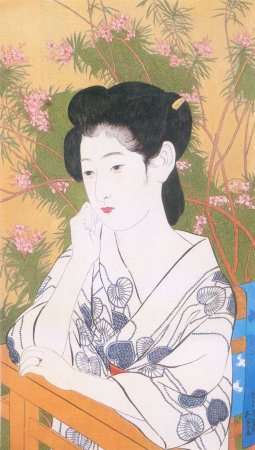

Yukata |

浴衣

ゆかた |

Literally translated as a bath garment.

A light summer garment made of cotton often used for casual attire or as a bathrobe. Most frequently decorated with designs dyed in indigo blues. "Yukata came from yukatabira (bathing katabira) to distinguish it from katabira or linen dress for ordinary summer wear. Originally yukatabira, as its name indicates, was worn after taking a bath, for drying up the body. Thus it took the role of bath towels at first. They used to put on one yukata upon coming out of the bath tub, and changed it for another until the body was thoroughly dried. Thus it was called minugui or body wiper."

Source: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, p. 53.

Yukatabira (浴衣びら or an alternative 湯帷子 ゆかたびら); katabira (帷子 or かたびら); minugui (?).

The image to the left is by Goyo. |

|

|

雪 ゆき |

|

|

There is an interesting passage in Snow Country Tales: Life in the Other Japan by Suzuki Bokushi (translated by Jeffrey Hunter with Rose Lesser, published by Weatherhill, 1986). Bokushi (1770-1842: 鈴木牧之 or すずき.ぼくし) lived in Echigo, modern Niigata Prefecture, "snow country". He wrote a wonderful comparison of his native region which was buried in snow every winter with that of Edo, modern day Tokyo. In the section entitled "The First Snow" he wrote: "The people of friendlier climates take pleasure in the snow. In Edo, where some years it doesn't snow at all, the first snow is regarded as especially delightful. People set out in little boats, accompanied by geisha, to watch the snow; important guests are invited to tea ceremonies held in the snow; the brothels use the snow as an excuse to encourage their patrons to spend the night; and the restaurants and bars regard snow as an omen of many customers. It is difficult to count the many entertainments in the snow that have been devised. But the great degree to which the snow is celebrated in Edo is a mark of that city's great plenty. The people of the snow country can't help but be envious when they see and hear these things. The difference between the first snow in Edo and our first snow is the difference between pleasure and pain, clouds and mud." (p. 10)

|

||

|

|

||

|

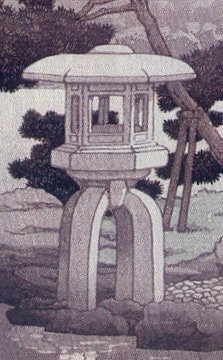

Yukimi dōrō |

雪見灯籠

ゆきみ.どうろう |

Literally a snow viewing lantern. It is said that the 'snow viewing' part has more to do with the beauty created by the newly fallen snow as it piles up on top than it does for the way the lantern illuminates its surroundings.

The yukimi dōrō is only one type of stone lantern or ishi dōrō (石灯籠 or いし.どうろう). Mock Joya states that there are 200 varieties of stone lanterns.

Despite what you might read at some sources that claim to be the definitive answer this type of stone lantern can have either three or four stone legs.

The image to the left is a detail from a print by Hasui from 1938. 1 |

|

Yukiwa |

雪輪

ゆきわ

|

The snow circle or

ring motif:

Quote from: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, p. 42.

|

|

Yumiya |

弓矢

ゆみや

|

Bow and arrow.

The image on the left in the center is a detail from a Kuniyoshi Suikoden print. Above is a close-up showing the descent of a flying goose which has just been struck through. On the bottom is an enlarged detail of the quiver with arrows.

This figure represents Shōrikō Kaei. "The manner in which Kaei holds his bow is unusual: the string of the bow is depicted on the left side of his left arm which would make it extremely difficult to shoot an arrow with the right hand."

Quote from: Of Brigands and Bravery: Kuniyoshi's Heroes of the Suikoden, by Inge Klompmakers, Hotei, Leiden, 1998, p. 86.

Shortly after I posted

the information shown immediately above I received an e-mail from a fellow I

know to be an adept at or expert in quite a few areas including ukiyo-e,

Kuniyoshi, etc. What I didn't know is that he is also extremely

knowledgeable about archery. He said that

Klompmakers statement is incorrect: "Anybody who has used a reasonably

powerful bow knows that after the release of the arrow the bow tends to whip

round into the position shown. Most archers will wear a leather wristguard

on their arm because the impact can sting

Then yesterday, June 15th, 2006, I received another e-mail from an expert in Portugal:

"In Japanese

archery, when releasing the string... the bow rotates almost 360 degrees, so

the string travels from the right side of the bow arm until almost or even

touching the arm on the left side. the bow performs an almost perfect circle

around itself. This is called 'Yugaeri' [弓返り or ゆがえり]. A perfect shot

has a perfect yugaeri, so in the image, the string being on the left

side of the bow arm, just means that it was a flawless shot.

Now this is dynamite information and I want to thank Carlos Freitas, President of the Portuguese National Archery Federation for it.

In defense of Klompmakers it seems to me that ignorance of the fine points of Japanese archery would make this kind of mistake reasonable.

The Kuniyoshi image to the left was sent to us by our great contributor E. Thanks E! |

|

Zakuro |

石榴

ざくろ |

Pomegranate: "...blessed with many seeds, represents the wish for numerous progeny and the attainment of sexual maturity by a woman." Along with the peach and the Buddha's hand, a type of inedible citron, they formed what the Chinese believed were the Three Abundances.

Quote from: Symbols of Japan by Merrily Baird, p. 65.

This illustration comes from the 1817 edition of the Kaishi garden which was first published in Japan in 1748 "...as the first rendering of the Chinese 'mustard seed garden' ".

This image was generously contributed to our site by E. Thanks E! |

|

Zangiri-mono |

残切物 ざんぎりもの |

Stage works with a modernized Western flair. Literally means "cropped-hair piece." 1 |

| Zarusoba |

笊蕎麦 ざる そば |

Cold served soba 1 |

|

Zōhan |

蔵版 ぞうはん |

Translated as "copyright." One of the great joys of working on this site is finding new material to research. Such it is with the term zōhan which I hadn't recalled ever seeing before reading an entry in a recently published Roger Keyes book I just purchased: Ehon: The Artist and the Book in Japan published by the New York Public Library and the University of Washington Press, 2006, p. 80. But copyright might not be exactly right. In fact, it may mean more the ownership of the woodblock from which an image or text was published. 'Copyright' may be more a Western concept in this case although the similarities are clear. Remember, the use of this term might be important when printed in a book or on a sheet because blocks were often sold off by one publisher to another for later editions. Business is business. The publisher owned the blocks and not the artist.

In my stumblings I also ran across another zōhan made up of two different kanji characters: 像板. These translate as 'image block'. Perhaps these two zōhans were interchangeable. Perhaps not. Keyes would know. |

|

Zōri |

草履 ぞうり |

Sandals |

|

Zuishin |

随身

ずいしん |

"Zuijin [ずいじん]. 'Attendant deities'. Warrior-type guardians, often carrying bows and arrows. As protector of [Shinto] shrine gates they are known as kado-mori-no-kami. They are associated with dosojin, protector of crossroads and other boundary areas."

Quote from: A Popular Dictionary of Shinto, NTC Publishing Group, 1997, p. 229.

"At the entrances of many Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples there are statues of huge gate guards. These wood sculptures are housed in gate buildings which are often magnificent and towering structures.

The guard gate of a Shinto shrine is called Zuishin-mon. Zuishin were the ancient Court guards who were detailed to guard the Emperor, princes and high officials. So the guard figures at the shrine are made after those ancient officials and dressed in Court costume, carrying swords, bows and arrow-holders. They always come in pairs, one standing at each side of the entranceway, to protect the shrine from evil and wrong-doers."

Quote from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, p. 521.

To the left is a detail from a print by Kuniyoshi. |

|

Zukushi |

尽くし ずくし |

|

|

|

A thru Ankō |

|

|

Aoi thru Bl |

Bo thru Da |

De thru Gen |

Ges thru Hic |

Hil thru Hor |

|

Hos thru I |

|

J thru Kakure-gasa |

|

Kakure-mino thru Ken'yakurei |

|

|

Kesa thru Kodansha |

|

|

Kōgai thru Kuruma |

Kutsuwa thru Mok |

Mom thru N |

3.jpg) O thru Ri |

Ro thru Seigle |

Sekichiku thru Sh |

Si thru Tengai |

Tengu thru Tsuzumi |

HOME

HOME