|

|

JAPANESE PRINTS A MILLION QUESTIONS TWO MILLION MYSTERIES |

|

|

|

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画

Port Townsend, Washington |

|

|

|

Sekichiku thru Sh Index/Glossary |

|

|

|

The gold koban coin on a blue ground is being used to mark additions made in June 2008. |

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

Sekichiku, Sen, Sendai Hagi, Seno Juro Kaneuji, Seppuku, Seriage, Seridashi, Shakujō, Shamisen, Shank's Mare, Shibaraku, Shide, Shigenobu, Shigoki, Shiitake tabo, Shika, Shima, Shimenawa, Shini-e, Shini sōzoku, Shintai, Shinzō, Shiokuni, Shiori, Shippō, Shiranami-mono, Shiratama, Shirizaya-no-tachi, Shishi, Shishimai, Shōchikubai, Shokudai, Shuro and Shushoku

石竹, 銭, 先代萩, 瀬尾十郎兼氏, 切腹, 迫上, 迫出,錫杖, 三味線, 暫, 紙垂, 重信, 志ご貴, 椎茸髱, 鹿, 縞, 七五三縄 or 注連縄, 死絵, 新造, 死に装束, 神体, 新造, 汐汲み, 栞, 七宝, 白浪物, 白玉, 尻鞘の太刀, 獅子, 獅子舞, etc. |

|

|

TERM/NAME |

KANJI/KANA |

DESCRIPTION/ DEFINITION/ CATEGORY Click on the yellow numbers to go to linked pages. |

|

Sekichiku |

石竹

せきちく |

Pink motif used as a family crest or mon. |

|

Sen |

銭

せん |

This motif represents the sen which is one hundredth of a yen. "In a society said to despise both merchants and money, the appearance of coins as a heraldic motif may seem surprising." Originally the Japanese did not mint their own coins, but imported them from China. This formed a major part of their trade.

Coins were also important in the Buddhist death rituals. Six coins were placed by the body of the deceased to help the soul on its journey to the nether world. This would act as alms paid to six gods of the afterlife.

Source and quote from: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, p. 108.

Mock Joya gives a slightly different explanation for the use of the funereal coins: "...copper coins, or pieces of paper on which the outlines of coins were roughly painted, were placed in the coffin. The ancients believed that Sanzu-no-kawa (Sanzu River) divided this world from Gokuraku (Paradise), and so coins were required to pay for the ferry ride across the river. Since they also believed it was a lengthy journey to Gokuraku straw sandals and a strong staff to lean on were placed in the coffin to aid the traveler."

Quoted from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese (p. 317) |

|

Sendai Hagi |

先代萩 せんだいはぎ |

Alternate name for the kabuki play "Date Kurabe Okuni Kabuki" 1 |

|

Seno Juro Kaneuji |

瀬尾十郎兼氏 せんお.じゅうろう.かねうじ |

Character from the kabuki play "Genpei Nunobiki no Taki" 1 |

|

Seppuku |

切腹 せっぷく |

A form of ritual suicide through disembowelment. Also known as harakiri. |

|

Seriage |

迫上

せりあげ |

A trap lift for actors.

"The stage itself, in wing space, position of lighting instruments, facilities for flying scenery and so forth, follows the Western model. However, the stage retains the use of machines which were developed by the Japanese independently of their development in other countries. These are the seridashi, the seriage, and the mawari-butai."

"The first use of the seriage... appeared in 1736."

Quotes from: The Kabuki Theatre, by Earle Ernst, University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 1974, p. 29.

"A half century prior to the revolving stage, various types of traps were introduced to kabuki. Generically, all these devices, which raise actors or scenery up to the stage level through a hole in the floor or lower them out of sight, are called seri, literally 'press' or 'push.' When a trap is raised, this is referred to as seriage, 'push up,' or seridashi, 'push out.'

Quote from: Studies in Kabuki: Its Acting, Music, and Historical Context, by Brandon, Malm and Shively, Published by the Institute of Culture and Communication East-West Center, 1978, p. 116. |

|

Seridashi |

迫出 せりだし |

A trap lift for scenery for the kabuki theater.

"The seridashi is a trap-lift which brings scenery from below to the level of the stage floor and vice versa. This invention of Namiki Shōzō seems to have first appeared in November 1727."

Quote from: The Kabuki Theatre, by Earle Ernst, University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 1974, p. 29. |

|

Settsugekka (Snow, Moon, Flowers) |

雪月花

せつげっか

|

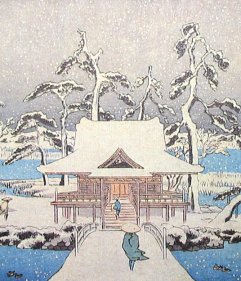

A popular motif in Japanese art which has its origins in 6th century China intellectual theory. Composed by Xie He [謝赫] the "Six Rules of Painting" were published in three volumes: 'Snow', 'Moon' and 'Flowers'.

Merrily Baird stated: "The Japanese term 'snow, moon, and flowers' (settsugekka) refers to the Three Beauties of Nature, with each of the beauties said to be a reminder of the transience of life."

Source: Merrily Baird, Rizzoli International Publications, Symbols of Japan: Thematic Motifs in Art and Design, 2001, p. 38.

To the left are three details from a series of prints by Hiroshige originally published in ca. 1843. The series carried the title Meisho setsugekka (Famous Places of Snow, Moon and Flowers). |

|

Shakujō |

錫杖

しゃくじょう

|

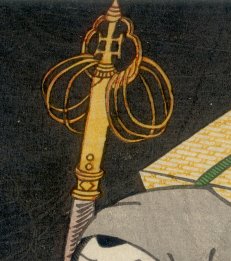

"...a wooden staff with metal cap on which a metal ring is loosely hung so that a jingling noise is made in walking. This noise is intended to warn beetles, snakes, and other small creatures on which the monk might possibly tread of his approach so that they can get out of the way."

Quoted from: The Shambhala Dictionary of Buddhism and Zen, p. 192.

A pilgrim's staff is also referred to as a kongodue (金剛杖 or こんごうづえ). Because it warns creature of its approach it is known in China as an alarm staff. But the jingling serves another function in that it is meant to drown out all other worldly sounds from the ears of the carrier.

The Buddha was said to have used a sandalwood staff with pewter head and rings.

Source: Chinese Symbolism and Art Motifs, by C.A.S. Williams, Castle Books, 1974 edition, p. 5.

|

|

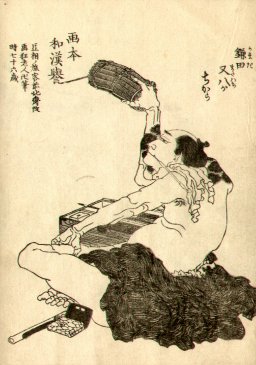

Shamisen |

三味線

しゃみせん

|

"A three-stringed plucked lute that was originally associated with the urban world of the pleasure quarters and theaters of the Edo period (1600-1868) and later became a concert instrument as well. It is called samisen in the Kyōto-Ōsaka area and the sangen when used in classical chamber music."

The shamisen may have its origins in a similiar instrument found in China, but definitely is traceable to one from the Ryūkū Islands. "Both the Okinawan (sanshin or jamisen) and the Chinese (sanxian or san-hsien) forms are still used today, but they differ greatly from the instrument used in Japan."

Shamisens vary in length from 3.6' to 4.6' according to the sound desired. "They are generally distinguished by the thickness of their unfretted fingerboard, but other differences are found in string gauges, bridge weights, body sizes, and the design and size of the plectrums (bachi). The wooden quince, and the heads which cover the front and back of the body are cat or dog skin. Pegs and plectrums are ivory, wood, or plastic. Strings are twisted silk or nylon." Of course the plastic and nylon parts were not available during the Edo period.

Source and quotes from: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan entry by William P. Malm (vol. 7, pp. 76-7) |

|

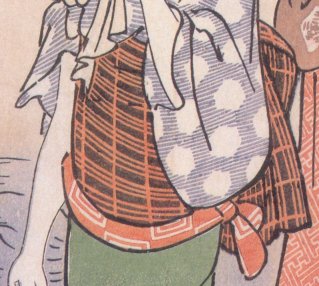

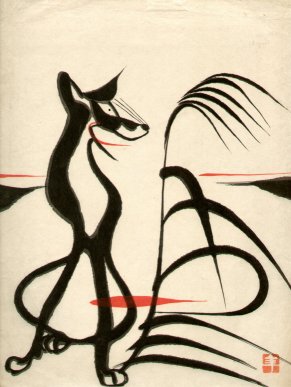

The image to the left is a detail from a print by Eizan showing a geisha holding her shamisen. The detail below shows what is probably intended to be an ivory plectrum or bachi (撥 or ばち).

"A geisha is often called a neko [i.e., cat]; but it is because cats' hides are used in making shamisen, their musical instrument. But some say that it is because a geisha is also to be petted."

Quoted from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese (p. 114)

According to Mock Joya the shamisen is of unknown origin and may have originated in Siam. It was introduced into Japan via the Ryūkūs during the Eiroku era (1558-1570). "It was a biwa (lute) player named Nakashoji who took interest in the new instrument when it first came to Sakai." In the Ryūkūs it was called a jahisen (snake-skin string) because that was what was used to cover the sound box. There it was played with a bow, but Nakashoji replaced that with the plectrum he used to play the biwa. He also made sound changes. "As it was impossible to obtain snake skins for the instrument, he covered it with cat-skin." Source and quotes from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese (pp. 494-5). |

||

|

|

||

|

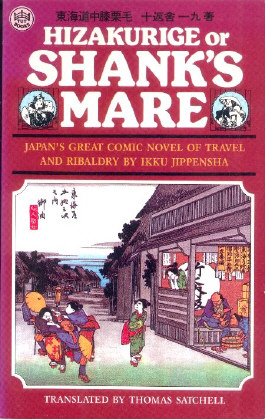

Shank's Mare |

|

A classic, serial, comic novel by Jippensha Ikku ( (1765-1831: 十返舎一九 or じっぺんしゃ.いっく) which first appeared in 1802. It follows the adventures of two "amiable scoundrels", Yajirobei and Kitahachi, as they travel from Edo to Kyoto via the Tōkaidō road. The title in Japanese is the Tōkaidō Hizakurige ( 東海道膝栗毛 or とうかいどう.ひざくりげ). Although this book is a bit ribald it should be a must read for anyone interested in the culture of that age.

The original publisher in Edo may have been Yamashiro-ya Sahei (山城屋佐兵衛 or やましろや.さへえ).

|

|

Source and quotes from: World Within Walls: Japanese Literature of the Pre-Modern Era 1600-1867, by Donald Keene, published by Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1976, pp. 412-13. |

||

|

|

||

|

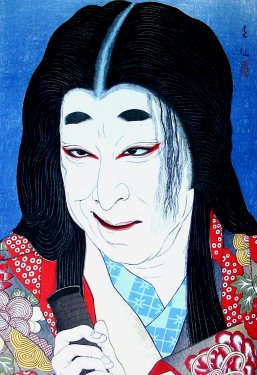

Shibaraku |

暫 しばらく |

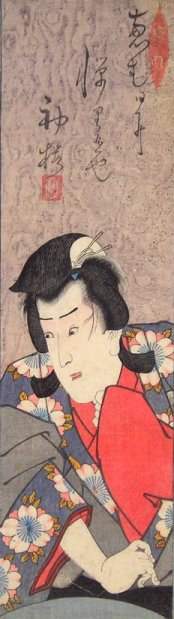

"Stop Right There!": One of the greatest and most dramatic moments of the kabuki theater occurs when the hero is walking down the hanamichi or walkway toward the stage dressed in a spectacular persimmon red costume. Just as a murder is about to take place he yells "Shibaraku".

This role was created by Ichikawa Danjūrō II (1688-1758). In time this became the opening act of the season opener no matter what play was being performed. "Just a Minute! is one of hte finest examples of the Danjūrō family style (ie no gei), its hero powered by godlike qualities of magnificence, might, and theatricality but also contained roles of every type (yakugara), thus effectively presenting the members of the new troupe through the display of their varied talents."

Quote from: Kabuki Plays on Stage: Brilliance and Bravado, 1697-1766, vol. 1, edited by James R. Brandon and Samuel L. Leiter, University of Hawai'i Press, 2002, p. 44.

"More than a play, Shibaraku is a time-honored ritual based on the folk tradition of good repelling evil. The semihumorous plot, replete with witty wordplay, reflects the pleasure-seeking spirit typical of the common people in the Edo period."

Quote from: The Kabuki Guide, by Masakatsu Gunji, Kodansha International, 1987, p. 122.

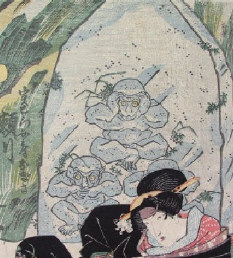

The detail to the left is from a print by Toyokuni I.

The term shibaraku can be translated a number of ways: little while; Wait A Second!; Wait A Minute!; Wait!; Stop Right There!; and probably a few more I am not aware of. |

|

Shide |

紙垂 しで |

The zig-zag, cut paper streamers attached to a sacred wand made from a sakaki (榊 or さかき) tree used in Shinto rituals to ward off evil spirits. They also are added to shimenawa which are the twisted straw rope which indicate a sacred space.

(See tamagushi, sakaki, nusa and shimenawa.) |

|

Shigenobu |

重信 しげのぶ |

|

|

Shigoki |

志ご貴

しごき |

A sash of soft cloth tied under the obi. It can be used to tie up flowing robes or to tuck them in whenever necessary - like when one is wading through water.

|

|

Shiitake tabo |

椎茸髱

しいたけたぼ |

A hairstyle "...with the sidelocks drawn out in 'mushroom' shapes."

Quote from: The Passionate Art of Kitagawa Utamaro, published by the British Museum Press, London, 1995, text volume, p. 150.

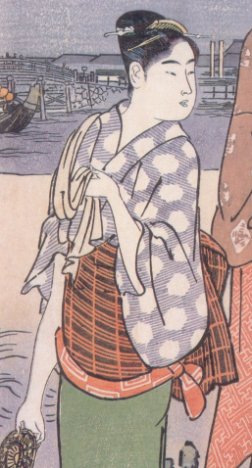

I won't swear to it, but I think the detail from the print by Toyohiro to the left illustrates an example of a bijin with a shiitake tabo hairstyle. |

|

Shika |

鹿

しか

|

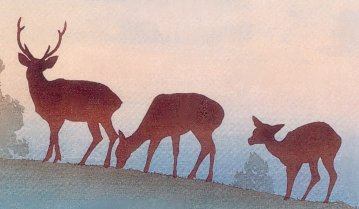

Deer have an ancient connection with religious belief system throughout Eastern Asia. In China Taoists thought that deer were able to find the Fungus of Immortality. In Japan they came to be associated with the kami or gods. In fact, deer are often seen as companions to two of the Seven Propitious Gods.

Fake deer heads were often donned like masks for dances during festivals and antlers became a symbol of strength and virility. Stylized representations adorned the helmets of warriors or were used in family crests. Even the wearing of deer skins was thought to be empowering.

Shamanistic divinations were made from deer bones. Pulled from a fire and allowed to cool the cracks were read, i.e., interpreted. The Chinese practiced the same art but with bones and shells of other creatures.

The image of the deer on the green grass to the left and on top is from a photo I shot from my balcony here in Port Townsend, Washington. The image in the center is a detail from a 20th century print by Koitsu. The one on the bottom was sent to me by a correspondent in Maine. Thanks D! |

|

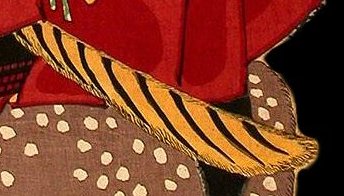

Shima |

縞

しま |

Stripes - a common fabric pattern |

|

Shimenawa |

七五三縄 or 注連縄

しめなわ |

Braided rice straw ropes which have the power to keep evil spirits away. |

|

Shini-e |

死絵 しにえ |

"Death Print" or memorial print: Literally a death (死) picture (絵). They had also been referred to earleir as tsuizen-e (追善絵 or ついぜんえ). This term has a very clear association with a Buddhist service in commemoration of the anniversary of a death. 1, 2 |

|

Shini sōzoku |

死に装束 しにしょうぞく |

Light blue court robe worn for burial or suicide 1 |

|

Shintai |

神体

しんたい |

A physical object in which a kami, i.e., god, is said to be exist. 1 |

|

Shinzō |

新造 しんぞう |

The lowest order of official prostitutes who also attend to the needs of the highest ranking courtesans. 1 |

|

Shiokumi |

汐汲み

しおくみ |

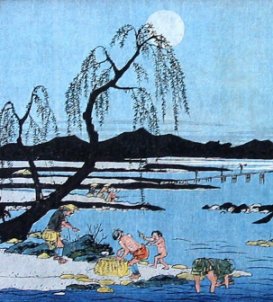

Salt gatherering or gatherer: Enden (塩田 or えんでん) or salt fields were historically the main source of salt in the Japanese diet. Saltwater from the seaside could be boiled down or sand deposits laden with copious amounts of salt could be doused with seawater and then boiled to render an edible product. |

|

Years ago I attended the lectures of a visiting scholar, Raymond Mauny, who stressed the importance of the ancient salt trade routes in West Africa. These traversed the Sahara at great peril. However, salt was so highly valued that it was traded for gold and other precious items.

In 1930 Gandhi led a group of men on a march to the sea to gather salt in contravention British orders. The British had imposed a salt tax which Gandhi thought iniquitous.

"When an unwelcome visitor finally leaves the house, the old-fashioned housewife will hurry to the kitchen and, taking a pinch of salt, scatter it all over the house entrance." This is an act of purification which always overpower evil. Sumo wrestlers toss salt before a match to drive away evil spirits and as an indication that they will fight fairly. Even attendees at funerals purify themselves with salt before reentering their homes.

Source and quote from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, pp. 305-6.

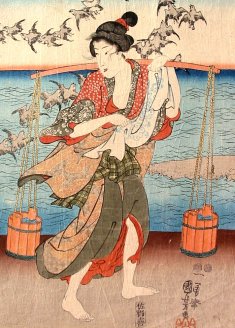

The story of the salt gathering maidens was a popular theatrical theme. In short: "Literary works based on the legend of the sisters Matsukaze [松風 or まつかぜ] and Murasame [村雨 or むらさめ] began with the medieval nō play Matsukaze. In the Edo period, the story develops in many directions, but plays for the puppet and Kabuki theatres are known as 'Matsukaze' pieces'... When performed as a Kabuki dance, the title is always 'Shiokumi' (Drawing Brine). Ariwara no Yukihira [在原の行平 or ありわらのゆきひら], who had been exiled to Suma, falls in love with both the sisters Matsukaze and Murasame, who live by the sea making salt from the brine. When he departs to go back to the Capital, he gives them his golden court hat and hunting cloak..."

Quote from: The Passionate Art of Kitagawa Utamaro, entry by Timothy Clark, published by the British Museum Press, London, 1995, text volume, p. 155-6. |

||

|

|

||

|

Shiori |

栞

しおり |

Bookmark

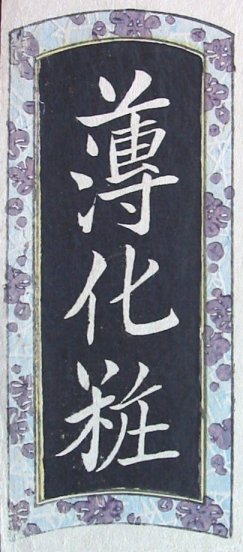

There was a time in the 18th century when the Japanese were believed to be the most literate people in the world. Naturally this would call for a lot of bookmarks. Whereas this might not seem particularly pertinent to a discussion of ukiyo prints it is. Many artists, such as Utamaro, often used a bookmark cartouche to post the title of a print series. In time some artists even designed whole prints mimicking the shiori itself.

The cartouche seen above is a detail from a print by Kunisada. (You can see the whole print by clicking on the number in the column to the right.) The image below is a detail from a print by Toyokuni III created in the shape of a bookmark. That image was sent to us by our great contributor Eikei.

Thanks 英渓!

Take a look at the prints you own. If your collection is large enough at least one of them will probably have a bookmark cartouche on it. Now you know what that form is called. That is, assuming my information is correct. Don't quote me.

Shiori-gata (栞形 or しおりがた) is the precise term used to indicate a bookmark-shaped cartouche. 1

|

|

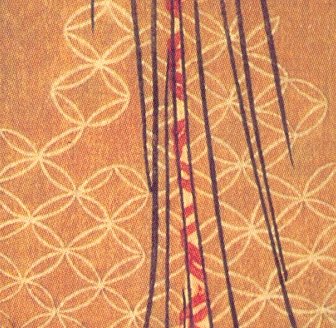

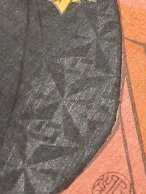

Shippō |

七宝

しっぽう

|

The Seven Treasures composed of gold, silver, pearls, agate, crystal, coral and lapis lazuli.

Shippo also has two other related meanings. The first is a Japanese term for cloisonné and the second is a decorative motif which displays none of the precious items listed above, but consists only of interlocking circles. See the image detail from a Kiyonaga print to the left.

"The shippo design appeared in the late Heian period as an abstraction from a large overall pattern of overlapping circles, the overlap being exactly equal on all four sides. Its name appears to derive from one of those inimitable Japanese puns, this one shi-ho, or 'four directions.' "

Quoted from: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, p. 134.

I have added the two family crests or mons at top left and below in order that you can see two variations on this motif.

This pattern is also referred to as shippo tsunagi (七宝繋 or しっぽう.つなぎ).

|

|

Shiranami-mono |

白浪物 しらなみもの |

Stage works with thieves and lowlifes as the heroes |

|

Shiratama |

白玉 しらたま |

A courtesan of the Tamaya brothel 1 |

|

Shirizaya-no-tachi |

尻鞘の太刀

しりざやのたち |

"...a removable fur sheath was provided for the scabbard to protect it from the weather. The type of fur used was determined by the rank of the wearer, and deer, wild boar, or bear skins were commonly used for this purpose."

Quote from: The Shogun Age Exhibition (cat. entry #19, p. 52)

The images to the left and below are from a detail of a print by Yoshitoshi from his "100 Aspects of the Moon".

|

|

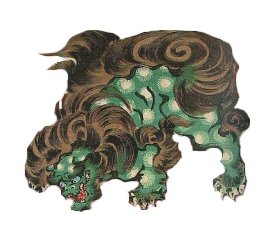

Shishi |

獅子

しし |

Lion 1 |

|

Shishimai |

獅子舞

ししまい |

Lion dance.

This lonely little, but festive lion dancer image to the left is a detail from a larger surimono. Although it is signed the signature is as yet unread. It has been sent to us by E., one of our favorite correspondents and a great and generous contributor to this web site. Thanks E! |

|

Shōchikubai |

松竹梅

しょうちくばい

|

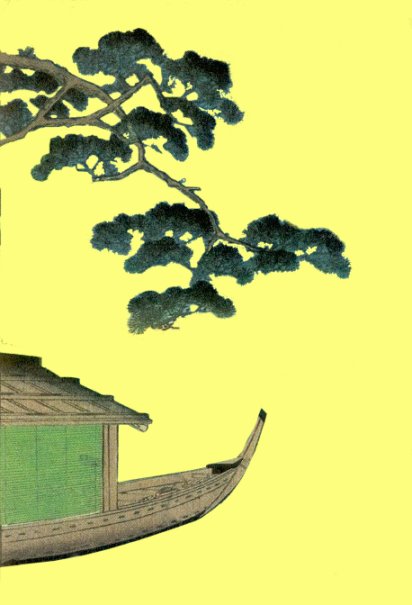

The Three Friends of Winter: The pine, bamboo and plum. "...an ensemble motif of Chinese origin that teams the pine, bamboo, and plum, which are all symbols of winter, long life, and the cultured gentleman. This convention of linking the three plants, which are consistently ranked in the same order...[are used] both as a design motif and an elegant system of designating such things as banquet rooms or menu options in traditional restaurants."

Quote from: Merrily Baird, Rizzoli International Publications, Symbols of Japan: Thematic Motifs in Art and Design, 2001, p. 38.

There is a long and evolved history of the use of these plants both together and separately in various other propitious combinations. They appear frequently on fabric designs, porcelains and on specially, privately published New Year's prints called surimono. The plants themselves are often used in New Year decorations.

The pine is associated with prosperity and endurance, the bamboo with long life and the plum with youth, renewal and beauty.

Shōchikubai may also be translated as 'high, middle and low ranking.'

These examples are being shown courtesy of Shu Suehiro at http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm. A great botanical site. You should visit it. |

|

The pine example is Pinus densiflora or Japanese red pine. The native name is Akamatsu (赤松 or あかまつ).

The bamboo shown above is Phyllostachys aurea and is commonly known as Fish pole or Golden bamboo. In Japan it is referred to as Hotei bamboo (布袋竹 or ほていちく). Hotei is the large bellied god of good fortune.

The plum is the Prunus mume or Japanese apricot, a member of the Rose family. The native name is ume (梅 or うめ). |

||

|

|

||

|

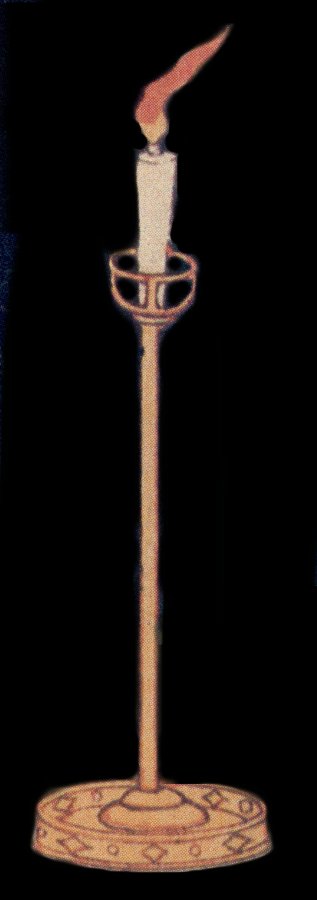

Shokudai |

燭台

しょくだい |

Candlestick or candlestand |

|

Shōmenzuri |

正面摺

しょうめんずり

|

Burnishing: Literally "front printing" - "...technique of rubbing surface of finished print over block carved in reverse in order to give polished texture to pattern".

Quote from: Japanese Print-Making: A Handbook of Traditional & Modern Techniques, by Toshi Yoshida & Rei Yuki, Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1966, p. 169.

"Polishing the front of a print on a block to bring out a shiny pattern."

Quote from: Japanese Woodblock Printing, by Rebecca Salter, University of Hawai'i Press, 2001, p. 123.

All of the examples to the left are from Toyokuni III prints. The middle one shows how one would normally see while looking at the printed image. The bottom image shows the same print if you were to take the time to move sheet so that the full effect of the shōmenzuri is made clear. Click on the numbers to the right to go to pages with fuller views. 1, 2

|

|

Shuro |

棕櫚

しゅろ |

The hemp palm motif was particularly popular during Heian times because it was both an aristocratic symbol as it had been in China and because of its exoticism. Occasionally it was later used as a family crest or mon. |

|

Shushoku |

手燭

しゅしょく |

A portable candlestick. This type of a lighting is also referred to as a teshoku (てしょく). |

|

|

A thru Ankō |

|

|

Aoi thru Bl |

Bo thru Da |

De thru Gen |

Ges thru Hic |

Hil thru Hor |

|

Hos thru I |

J thru Kakure-gasa |

|

Kakure-mino thru Ken'yakurei |

|

|

Kesa thru Kodansha |

|

|

Kōgai thru Kuruma |

Kutsuwa thru Mok |

Mom thru N |

3.jpg) O thru Ri |

Ro thru Seigle |

|

Si thru Tengai |

Tengu thru Tsuzumi |

Yakusha thru Z |

HOME

HOME