JAPANESE PRINTS

A MILLION QUESTIONS

TWO MILLION MYSTERIES

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画Port Townsend, Washington |

|

O thru Ri INDEX/GLOSSARY |

|

|

The bird on the walnut on a yellow ground is being used to mark additions made in July 2008. The gold koban coin on a blue ground was used in June. |

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

Obake, Oban, Obi, Obon, Ochanomizu, O-fuda, Ōgi, Ohaguro, Ohara Koson, Oiran, Oke, Okoso-zukin, Okubi-e, Omamori, Omohan, Omon-guchi, Oni, Onna budō, Onnadate, Onnagata, Onoe Kikugorō III, Orchid (Ran), Osaka, Osaka Prints, Otokodate,

William Perkin,

Plum (Ume), Polonius, Port Arthur, Prussian blue,

御守り, 主版, 大門口, 鬼, 女武道, 女伊達, 女形, 尾上菊五郎, 蘭, 大阪, 男伊達, 梅, 旅順, 版元, 雷神, 蓮華座, 六藝 and 輪宝

おばけ, おおばん, おび, おぼん, おちゃのみず, おふだ, おうぎ, おはぐろ, おはらこそん, おいらん, おいらんどうちゅう, おけ, おこそずきん, おくびえ, etc.

|

|

|

Obake |

御化け おばけ |

A monster, ogre or goblin. According to Kunio Yanagita (柳田 国男), the great modern expert on folklore (1875-1962), obake are different than yurei (幽霊 or ゆうれい) or ghosts. Obake haunt a particular place while yorei haunt a particular individual. Despite their ominous description obake are said to be more humorous than scary. |

|

Oban |

大判 おおばん |

A woodblock print size generally 15" x 10". This the most commonly encountered size for 19th c. ukiyo prints. |

|

Obi |

帯 おび |

The sash of a kimono and like the word 'torii' obi is a word which has entered our vocabulary. Often used in crossword puzzles. |

|

Obon |

御盆 おぼん |

A Buddhist celebration during which the deceased are said to visit the homes of their relatives for several days. |

|

Lanterns are hung to guide them home. Food is set for them and at the end lanterns are placed in rivers, lakes, ponds, etc. to aid the souls of the deceased to return to the netherworld. It is celebrated in some areas as early as mid-July and as late as mid-August in others. There are also regional variations in the practice of this event.

Often the spirits of the dead are accompanied by other more vengeful, uninvited spirits which have returned to wreak havoc and vengeance. Because of that the Obon dance is performed in an attempt to scare off the malicious spirits.

Celebrated as early as 657 this festival may have its roots in Zoroastrianism in Persia combined with Buddhist practices. Some sources say that the Buddhist monk Mokuren (もくれん) saw a vision of his deceased mother starving in hell and he offered her a bowl of rice. That was around July 15th and hence its origin and timing. |

||

|

|

||

|

Ochanomizu |

御茶ノ水 おちゃのみず |

A district of Edo/Tokyo 1 |

|

O-fuda |

御札

おふだ |

A protective charm. Note the wooden plaques strung together on a cord hanging around the figure's neck. 1 |

|

Ōgi |

扇

おうぎ |

A folding fan: The image to the left is only one of the motifs used for a family crest or mon. However, in this case it could also be used as a butterfly mon. This shows the level of creativity of the Japanese sense of design. |

|

In 1960 U. A. Casal in his "Lore of the Japanese Fan" published in the Monumenta Nipponica (p. 61) gave a reasonable explanation for why the Japanese never warmed to the feather fan like we did in the West and elsewhere. "...the feather-fan was never greatly developed in Japan. It would not be surprising if this were partly due to its connection with the killing of birds. Not only was killing contrary to all Buddhist tenets, and at times rigorously forbidden in whatever form, but anything dead was also taboo in Shintō."

Editorial note: While this information may seem obvious to you, it was an 'A-ha, I get it!' moment for me.

Ōgi are also called sensu (扇子 or せんす). The folding fan can also be called a suehiro (末広 or すえひろ).

The word ōgi has its origin in afugi (あふぎ) or "something which creates wind." This was its early pronunciation.

This is so Marx Brothers: "It is a recorded historical fact that Fujiwara Tadahira [藤氏忠平 or ふじわらただひら], who lived from A.D. 880 to 949 and gained a high reputation as an aesthete and dilettante, had a cuckoo painted on his fan, which he never opened without first without imitating the cry of the bird." (Casal - p. 75)

There is a legend that the Emperor Gosanjō (1069-1073: 後三条 or ごさんじょう) was a very frugal man. He owned and loved a hi-ōgi (檜扇 or ひおうぎ) or fan made of wood slats. As it aged and cracked he pasted paper onto it and the modern folding fan was born. (C. - 76)

In footnote 49 on page 95 "In the Orient it is considered highly impolite to breathe into another's face. The Buddha forbade garlic and other pungent herbs. It is possibly due to this belief in the breath's impurity that the underling has to kowtow when speaking to the lord: his breath is directed towards the ground and will not affect the atmosphere. Often the Oriental will hold his hand or his fan over the mouth when speaking..." Personally I wish this was done a little more in the West.

Another rule of etiquette was used when passing items from one person to another: "It being impolite, generally speaking, to pass a thing from hand to hand, a fan may serve as a tray, either to proffer or to receive. Begging monks never took alms except on a partly opened fan. (To open it completely would have looked greedy.) (C. - 95) In "The Tale of Genji" the prince is handed a delicate flower this way presented on a highly perfumed white fan.

"The Japanese actor, whether of the No or Kabuki stage, could not exist without a fan. With an incredibly calm mimic, wielding his fan he can "outline" any kind of object, suggest the thatched roofs of a village, the floating of a boat, the rising of smoke or the pouring of a liquid, even the appearance of some supernatural, weird being. By the clever manipulation of his fan, he can underscore his pensiveness, sorrow, jollity, or drunkenness." (C. - 96)

Casal argues (p. 101) that fans were carried in the winter too because of

their ancient linkage to function as a tool which could dispel evil spirits.

That is also the reason why all guests at weddings carried them. "For

At the name giving ceremony a prominent relative who would be comparable to our 'godfather' would present a baby boy with two ōgi representative of the two swords carried by the samurai which in their turn stand for "courage and endurance." (C. 101-2)

Every year the Emperor is presented with a special fan referred to as 'a humble thing' or kenjō (献上 or けんじょう). The front shows a flowering plant while the back is a plain black sprinkled with silver. (C. - 102)

Whenever a person would set out on a long journey friends would present the traveler with a fan with valedictory sayings painted on it. (C. - 103)

"In the early days of the telegraph in Japan, when poles and wires were full of hidden menaces to the natives, many of them would not willingly pass under the overhanging danger. If unavoidable, they would screen themselves against the diabolical wires by opening the fan and holding it over the head." (Ibid.) Is this so different from the controversy in modern society about living too close to power lines? |

||

|

|

||

|

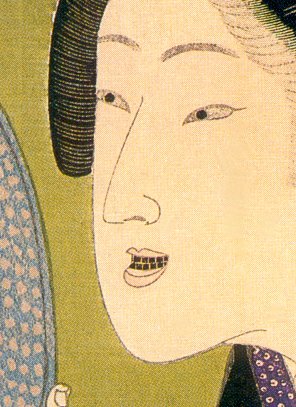

Ohaguro |

お歯黒

おはぐろ

|

Tooth blackening: An ancient practice going back to the Heian period, i.e., 9th century, whereby women mainly stained their teeth black. The dye was made from a mixture of oxidized "...iron shavings melted in vinegar and powdered gallnuts." During the Muromachi period (1336-1568) this practice gained popularity among the lower classes and "...was done from the age of puberty. In the Edo period (1603-1868), married women were required to dye their teeth black."

Quoted from: Dictionary of Japanese Culture by Setsuko Kojima and Gene A. Crane, p. 253.

The powder was often applied using a split-bamboo toothbrush.

(See also nurude.)

John Stevenson in Yoshitoshi's Women: The Woodblock Print Series "Fuzoku Sanjuniso" (Avery Press, 1986, p. 34) notes: "Blackened teeth were considered beautiful, possibly because teeth were a visible part of the skeleton, which as a symbol of death was unclean. Though teeth-blackening was the special mark of married women, courtesans also used it as a sign of adulthood. It formed part of the ceremony held for the debut of a trainee courtesan when she became a shinzo at the age of about fourteen." |

|

In The World of the Shining Prince: Court Life in Ancient Japan (pp. 203-4) Ivan Morris discusses several of standards used to judge beauty such as pale skin. The higher the rank the whiter the skin color had to be even if that meant applying layers of powder. "Heian women observed two customs that, attractive as they no doubt were to the gentlemen of the time, would hardly add to their appeal for Western men, or indeed for most modern Japanese. They plucked their eyebrows and then carefully painted in a curious blot-like set, either in the same place or about an inch above. They also went to the greatest trouble to blacken their teeth with a type of dye usually made by soaking iron and powdered gallnut in vinegar or tea. During later centuries this bizarre custom spread throughout the country and came to denote a woman's married status; in Heian times it was restricted t the upper classes, but not to married women."

Morris added a reference about the eccentric heroine of "The Lady Who Loved Insects". She refused to shave her eyebrows or blacken her teeth and this disgusted both her attendants and a potential suitor. "'Ugh!' said one of her maids. 'Those eyebrows of hers! Like hairy caterpillars, aren't they. And her teeth! They look just like peeled caterpillars.' A certain Captain of the Guards, who has been interested in the girl, is put off by her dark, thick eyebrows, which give her face an unpleasing boldness, and particularly by her unblackened teeth, which gleam horribly when she smiles.'" (p. 204)

In a footnote Morris notes that during the Han dynasty in China women plucked or shaved their eyebrows. However, tooth blackening appears to have been practiced only in Japan. Van Gulik argued that this fashion statement may have originated in the South Seas.

In a second footnote Morris states: "In the Tokugawa period, courtesans, who were know as 'brides of the night', also blackened their teeth."

In the Safflower chapter of The Tale of Genji the prince has returned to "His young Murasaki.... In deference to her grandmother's old-fashioned manners her teeth hand not yet received any blacking, but he had had her made up, and the sharp line of her [applied] eyebrows was very attractive."

Quote from: The Tale of Genji, by Murasaki Shikibu, translated by Royall Tyler, Viking Press, 2001, vol. 1, p. 130.

The mixture used for tooth blackening was referred to as hagurome (歯黒め or はぐろめ).

In Act 2: Scene 3 of the Tokaido Yotsuy kaidan Oiwa looks in the mirror and sees the results of the poison which her husband has given her. Despite her horrific disfigurement she prepares to go out. "Bring me my tooth blackening" she demands. Takuetsu, a masseur in the employ of her husband, argues against this: "But you are still sick and weak. You've just given birth. It's not safe for you to go out." She insists. Then it is noted that "She rinses her mouth, wipes her teeth dry, and then sits down in the center of the room. She rinses her mouth, wipes her teeth dry, and then applies the blackening.... She messily covers the corners of her mouth, which makes it look as though her mouth is monstrously wide."

Source and quotes from: Traditional Japanese Theater: An Anthology of Plays, edited by Karen Brazell, translation and commentary by Mark Oshima, Columbia University Press, 1998, p. 477.

Quote from: Tattoo in Early China, by Carrie Reed, Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 120, No. 3, Jul. - Sep. 2000, p. 363. |

||

|

|

||

|

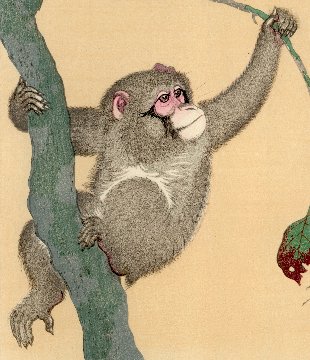

Ohara Koson |

小原古邨 おはらこそん |

Artist 1877-1945 1 |

|

Oiran |

花魁 おいらん |

Highest order of courtesan 1 |

|

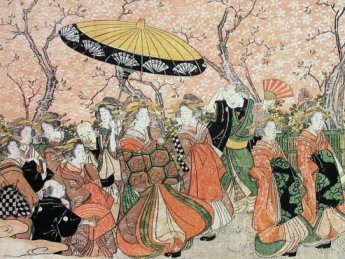

Oiran dōchū |

花魁道中

おいらんどうちゅう

|

A grand procession of courtesans: "Originally the word dōchū described the ceremonial processsion made by the shogun's officials between the cities of Kyoto and Edo. Since the Yoshiwara had streets named Edo and Kyoto, the procession of a courtesan to an ageya or a teahouse was likened to that of a grand daimyō."

Quote from: Yoshiwara: The Glittering World of the Japanese Courtesan, by Cecilia Segawa Seigle, University of Hawaii Press, 1993, p. 225.

Seigle adds: "...the procession of a leading oiran on the most formal occasion consisted of some twenty or twenty-one persons."

Ibid.

J. E. De Becker in his Yoshiwara: The Nightless City (p. 34) stated: "In the old days the tea-houses in Ageya-machi were allowed to contruct balconies on the second stories of their establishements for the convenience of those guests who desired to witness the procession of courtesan (Yūjo-no-dō-chū) that formed one of the most interesting features in the life of the Yoshiwara."

"The high-ranking courtesans all have male attendants, who hold parasols over them and their teenage shinzō (protégés). The girls are kamuro (attendants). The parasols are used here as symbolic markers of status rather than serving any practical function."

Quote from: The Women of the Pleasure Quarter: Japanese Paintings and Prints of the Floating World, by Elizabeth de Sabato Swinton, et al., Hudson Hill Press, 1996, p. 54.

The top example to the left is a detail from a print by Eizan. The one at the bottom is from a Yoshitoshi print and is here taken out of context, but is being used to help convey the concept. |

|

Oke |

桶

おけ |

Bucket: The image to the left shows a detail from a print by Kuniyoshi where Danshichi Kurobei is washing off the blood of his father-in-law whom he has just slain. This image was sent to us courtesy of E. Thanks E!) |

|

Okoso-zukin |

お高祖頭巾

おこそずきん |

A scarf or kerchief formerly worn by women during cold and/or inclement weather. In a bitter, frigid wind only the eyes were left visible. Clearly the okoso-zukin could be adjusted to meet the conditions.

As you may have noticed there seems to be a specialized word or phrase for just about everything. Take as an example this garment. I had seen it in prints by Kiyonaga, Utamaro, Eisen and Kunisada among others, however it wasn't until recently that I found a specific reference naming it. What I can't be sure of is the color. Most frequently it is black, but sometimes I think it could be white too. And what about similar coverings worn by men? Are those also referred to as okoso-zukin?

A thought: I don't know about you, but just knowing the name of something somehow helps me understand the milieu in which it existed. That is one of the purposes of this list of index/glossary pages. Yet there is so much more to discover. It is never ending. The tip of the iceberg. |

|

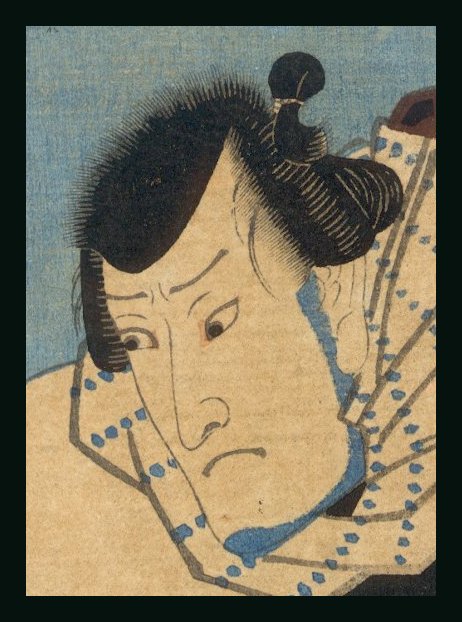

Okubi-e |

大首絵

おくびえ |

Large portrait head 1 |

|

Omamori |

御守り おまもり |

An amulet or charm |

|

Omohan |

主版 おもはん |

The omohan is the key block from which all of the black line prints are pulled. Generally there is one line print for each color (or area) of the finished product. Then separate blocks are carved based on the images printed from the omohan. |

|

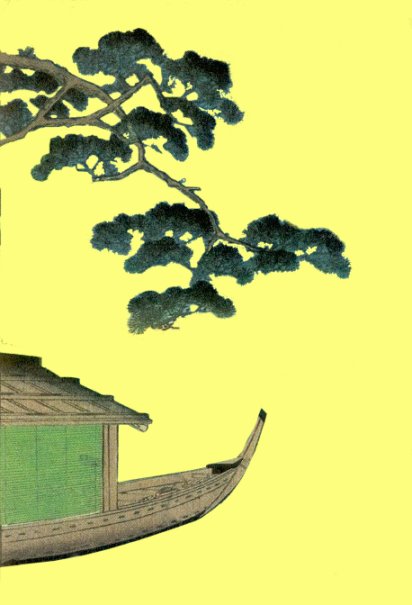

Ōmon-guchi |

大門口

おおもんぐち |

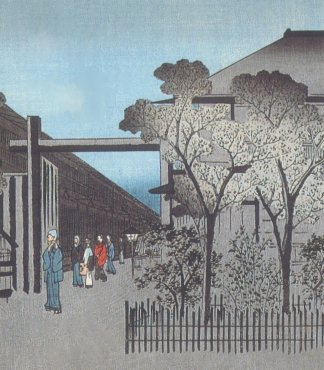

The entry gate into the Yoshiwara red-light district. The image to the left is a detail from an 1858 Hiroshige print showing clients leaving the Yoshiwara through the Omon Gate at dawn. |

|

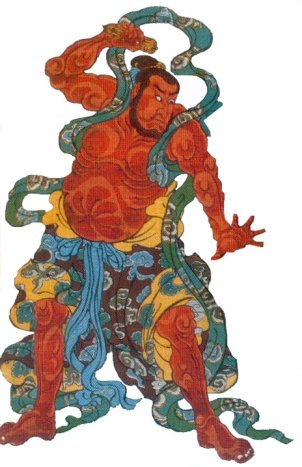

Oni |

鬼

おに |

A demon, devil, ogre or evil spirit. (In Japan in the game of tag when touched the person is not told you're 'it', but is called the 'oni'.) In hell it is red and blue oni which torment the dead. |

|

Onna budō |

女武道

おんなぶどう |

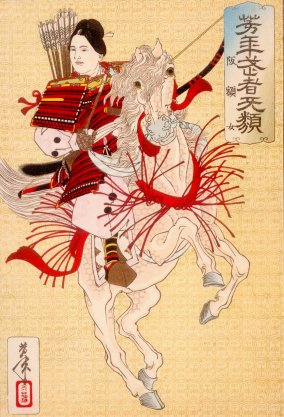

A female warrior.

The image to the left is from a print by Yoshitoshi of Hangaku Gozen (板額御前 or はんがく.ごぜん). |

|

Onnadate |

女伊達 おんなだて |

"...a female champion of the oppressed..." Her male counterpart is the otokodate. (See that entry below.) |

|

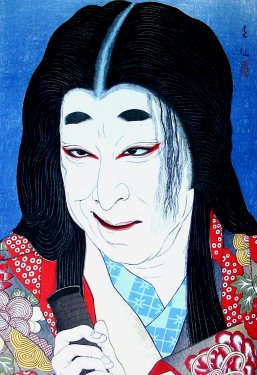

Onnagata (or oyama) |

女形

おんながた

|

A male actor performing in a female role in the kabuki theater. There is a long tradition of male only theater. In Shakespeare's day this was true. However, in Japan kabuki was first performed by women - that is until they were outlawed. Then young boys played many of the female roles until, of course, they were outlawed too. There was nothing left to do for the theater than to adapt and to draw on the talents of its remaining all male casts. Many of these men who were definitely heterosexual at home became the paragons of femininity and were often the trend setters for real women who chose to emulate them.

The image to the top left is a detail from the 20th century master Natori Shunsen (名取春仙 or なとり.しゅんせん) of Nakamura Tokizo as Yamauba Yaegiri from 1952. The one below that is by Toyokuni III from 1849-53.

One of the tell tale signs that you are looking at an onnagata print is the cloth which covers a part of the forehead. (See our entry for murasaki bōshi.) However, this is not always true and can be a tricky matter when one is trying to identify the subject matter. The bottom example to the left is just such a case. Although it is clearly identified and known to be an onnagata there is no murasaki bōshi. That example is also by Toyokuni III from 1860. 1, 2

The kanji for onnagata, 女形, can also be read as oyama and these terms seem to be interchangeable with each other.

|

|

Onoe Kikugorō III |

尾上菊五郎

おのえ.きくごろう |

Kabuki actor (1784-1849). He took the name Kikugorô III in 1815. |

|

Orchid (Ran) |

蘭

らん

|

One of the "Four Gentlemen" or Shikunshi which are flowers which mirror positive human traits. The other three are plum, bamboo and chrysanthemum. Borrowed from the Chinese and linked to confucian concepts.

"One of the 'four princes' of Chinese painting, the orchid nonetheless failed to attain even middle-class status in Japanese heraldry, and was one of the more neglected design motifs. No family appears to have used it as a crest."

Quote from: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, published by Weatherhill, 1991 edition, p. 66.

The quote seen above is rather odd because there are at least ten different designs for crests or mon using an orchid pattern which I am aware of. If families didn't use them then who did? Businesses? And why? 1 |

|

Ōsaka (as regards their prints vs. those of Edo) |

大阪 おおさか |

City second only to Edo in the production of Ukiyo prints. |

|

"The Ōsaka printers used a wider range of colours than those from Edo. Their number of basic pigments was greater, while also more mixtures were made, mixtures of the basic pigments with each other, and with black and white. In two or three black pigments, often applied with refinement and highly determining the atmosphere of a print."

Quote from: Ōsaka Kagami, by Jan van Doesburg, published by Huys den Esch, 1985, p. 6.

"Despite the considerable contact with developments in Edo, since both actors and artists travelled freely between these centers, the prints produced in Osaka have an individual character which usually renders them unmistakable."

Osaka "...prints date almost exclusively from the first half of the nineteenth [century]. Typically they are finely engraved and printed, with pure, opaque pigments on high-quality paper. Editions were small and often for private rather than public circulation and many of the artists were either amateurs or, at most, part-time designers. Certainly by contrast with the professional artists of Edo there were few Osaka artist with any considerable output..."

Quote from: The Art of Japanese Prints, by Richard Illing, published by Gallery Books, 1983, p. 145.

"The enthusiasm with which the great Japanese printmakers of Edo were suddenly discovered in Europe during the third quarter of the nineteenth century did not extend to their contemporaries in Osaka. In some ways this is strange..."

"As the stature of the Edo masters came to be recognized in the West, the Osaka school continued to attract little attention; instead, its flamboyance was dismissed with notable condescention." Only the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston purchased numerous Osaka prints.

Source and quotes from: The Theatrical World of Osaka Prints, foreword quotes by Evan H. Turner, Director, authors Roger Keyes and Keiko Mizushima, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1973, p. 9.

According to Keyes and Mizushima there are three reasons for the neglect of Ōsaka prints vis-à-vis those from Edo. The first is historical: The great center of production was Edo even when the output and innovations had been greatly influenced by styles already fully developed by artists from the Kyoto-Ōsaka region.

"The second unfortunate consequence of the notion that Japanese prints are an Edo art form has been the neglect of other schools.... The only regional prints to seriously rival those of Edo on their own ground of quality in design, engraving, and printing, were those produced in Osaka. But in a century of the study and collecting of Japanese prints, those of the Osaka school have been virtually ignored." Since they were neglected for so long they weren't available to students and collectors for study.

The third reason for the neglect of Osaka prints was due to the fact that they almost exclusively limited their subject matter to kabuki while Edo artists gave us warriors, ghosts, landscapes, beauties, parodies, erotica, etc.

Ibid, quotes by Keyes, pp. 15-17. |

||

|

|

||

|

Osaka Prints |

|

A good source book by Dean J. Schwaab published by Rizzoli in 1989. Lots of excellent information and color plates and a good source of material for students of this area of Japanese woodblock prints. 1 |

|

Otokodate |

男伊達

おとこだて |

A chivalrous commoner. Said to be a protector of the little man against abuses by samurai thugs and others abusing their authority. Although they were viewed somewhat the way we view Robin Hood that was probably a more romanticized than real interpretation. There were numerous such figures in late 18th and 19th century kabuki plays and ukiyo prints.

In time whole gangs of otokodate came together and may have preyed on the innocent themselves. In fact, some view them as the predecessors to today's yakuza.

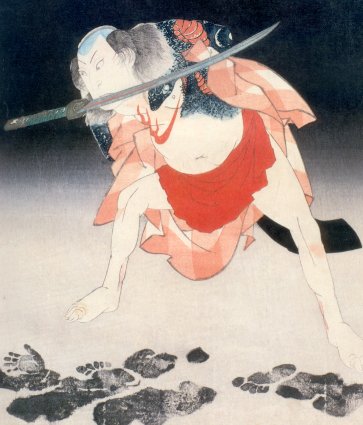

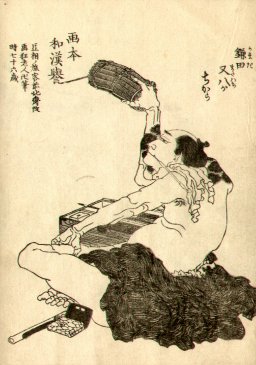

The detail to the left is an image of Danshichi Kurobei by Hokuei. Kurobei is only one of many otokodate featured in kabuki and in serialized printed books. After getting out of jail for killing the retainer to an evil samurai he is often portrayed either slaying his wicked father-in-law, covered in blood or washing the blood of from his extremely messy deed. |

|

Since otokodate were not allowed to carry samurai swords they armed themselves with anything at hand which could be used as a weapon: iron staffs or even heavy iron fans called tessen (鉄扇 or てっせん). "Their fans were so deadly that even they were afterwards proscribed. By then the smoking of tobacco had become habitual, and the otokodate smoked out of hardly less lethal, foot-long metal-pipes."

Quoted from: U. A. Casal in his "Lore of the Japanese Fan", Monumenta Nipponica, vol. 16, no. 1/2, 1960, p. 82

Sooooo... You must be asking yourself "Then why is Danshichi Kurobei holding a sword in his mouth in the image shown above?" Well, all I can say is 1) it must either be poetic license or 2) or he must have gotten ahold of a sword in the process of killing his wicked father-in-law or 3)... And you can fill in other possibilities here. |

||

|

|

||

| Perkin, William | Scientist 1838-1907. First creator of a synthetic aniline dye in 1856. | |

| Plum (Ume) |

梅

うめ |

One of the "Four Gentlemen" or Shikunshi which are flowers which mirror positive human traits. The other three are orchid, bamboo and chrysanthemum. Borrowed from the Chinese and linked to Confucian concepts. 1 |

| Port Arthur |

旅順 りょじゅん |

Scene of a Japanese victory over the Russian in 1905. 1 |

| Prussian blue |

プロシヤ青 |

A strong inorganic pigment imported into Japan beginning in the 1820s. 1 |

|

Publisher |

版元 はんもと |

|

|

Raijin |

雷神

らいじん |

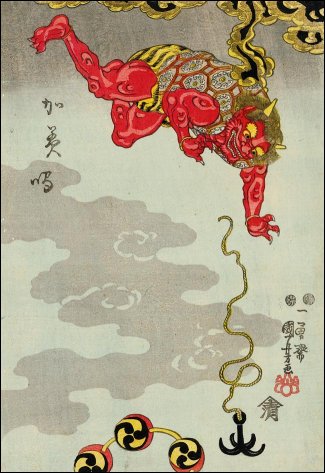

The god of thunder and lightning: Merrily Baird notes that "Japanese art depicts Raijin, who is also known as Raiden and Kaminari-Sama, in demonic form.... [W]hen he is without his thunderbolts, his primary attribute is a barrel drum or circlet of barrel drums decorated with the three-comma (mitsu tomoe) motif." (Symbols of Japan: Thematic Motifs in Art and Design p. 40)

"The rolling thunder is made by Kaminari-san [かみなりさん] or Raijin. He lives up on the summer clouds, and is always naked, wearing only a loincloth made of tiger skin. He has horns on his head and tusks in his wide mouth. On his back, he carries about a dozen round, flat drums, arranged in a circle, and holds drumsticks in his hands. When he beats his drums, the thunder rolls through the sky and puts fear into the people on earth. He comes down to this earth whenever he wishes to eat o-heso [お臍 or おへそ] or human navels. He is very fond of them, and this fondness causes him to fall from the sky. Whenever children run around naked in summer, mothers say, 'Put on your clothes or Kaminari-san will come and take your o-heso. Then little boys will hurry to cover themselves up. Many old people still put their hands on their stomachs whenever they hear the distant rolling of thunder."

Quoted from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, The Japan Times, Ltd., 1985, p. 345. |

|

The images shown above are from a print by Kuniyoshi from the early 1850s. Although I can't be sure it seems to represent an actor in a theatrical performance playing the role of the thunder god. These are shown courtesy of my great friend M. Thanks M! |

||

|

|

||

| Rain & Snow: The Umbrella in Japanese Art |

|

An excellent catalogue by Julia Meech of a show held at the Japan Society in New York in 1993. It includes a description of the techniques of production and a history plus annotated entries on everything from Kuniyoshi to Christo. |

| Rembrandt |

レンブラント |

The great 17th c. Dutch artist who occasionally used ganpi paper. 1 |

| Rembrandt: Experimental Etcher | Reprint of an exhibition catalogue which discusses the types of paper used by Rembrandt. 1 | |

| Rengeza |

蓮華座

れんげざ |

Lotus seat or throne: "The lotus is a symbol of purity and perfection because it grows out of the mud but is not defiled, just as Buddha is born into the world but lives above the world; and because its fruits are said to be ripe when the flower blooms, just as the truth preached by Buddha bears immediately the fruit of enlightenment."

Quote from: Buddhist Art by Anesaki found in Chinese Symbolism and Art Motifs, by C.A.S. Williams, Castle Books, 1974 edition, p. 257.

The lotus "...as an emblem seems to result from the wheel-like form... of the flower - the petals taking the place of the spokes and thus typifying the doctrine of perpetural cycles of existence."

Ibid.

The top image is a doctored version of one sent to us by our great contributor E! Thanks E! The one below is from a doctored image of a print by Yoshitaki. It is an example of a shini-e which is a death or memorial print. To see the full example of that print click on the example shown to the left. |

|

Rietberg Museum |

|

A museum of non-Western art in Zurich. (Here we are making a reference to an exhibition catalog with similar Eisen examples.) 1, 2 |

|

Rikugei |

六藝 りくげい |

The Six Accomplishments. |

|

These are the six arts which Confucian strove to master - literature (and calligraphy), arithmetic, etiquette, archery, horsemanship and music. I mention this because of a reference in a recent publication: Ehon: The Artist and the Book in Japan published by the New York Public Library and the University of Washington Press, 2006, p. 108.

Keyes points out that the rikugei are the underlying subjects of the "Colors of the Triple Dawn" by Torii Kiyonaga published in 1787. Only a scholar with Keyes level of expertise could have noticed. Today's casual viewer might enjoy the beauty of the prints or be drawn to the curious displays of everyday life in late 18th century Japan, but would inevitably miss the more profound subtleties. How could it be otherwise? We cannot be criticized fairly for our profound ignorance, but we should keep in mind that most if not all of the ukiyo images we look at are telling us a much greater story than meets the eye.

An aside: Haruo Shirane in his Early Modern Japanese Literature: An Anthology 1600-1900, Columbia University Press, 2002, p. 602 refers to horsemanship as charioteering. A minor point, but interesting all the same. |

||

|

|

||

| Rimbō |

輪宝

りんぽう

|

"The wheel is an

ancient Indian symbol of creation, sovereignty, protection, and the sun."

"The wheel represents motion, continuity and change, forever moving onwards like the circular wheel of the heavens." A wheel shaped weapon with sharpened blades was also used early on and came to be a symbol of protection and vengeance. "Buddhism adopted the wheel as a symbol of the Buddha's teachings and as an emblem of the...'wheel turner', identifying [it]...as the 'wheel of the law'." In Tibet the word for this wheel meant transformation or spiritual change. As a weapon the wheel "...represents the overcoming of all obstacles and illusions. Buddha's first discourse at the Deer Park in Sarnath is known as 'the first turning of the wheel of dharma'..." revealing the Four Noble Truths of suffering, its origin, its cessation and the path to the end of all suffering. Later discourses are the second and third turnings of the wheel of life.

The hub represents moral discipline and the eight spokes correspond to the Noble Eightfold Path of "...right understanding, thought, speech, action, livelihood, effort, mindfulness and concentration."

Source and quotes from: The Encyclopedia of Tibetan Symbols and Motifs, by Robert Beer, published by Shambala in Boston in 1999, pp. 185-6

The image to the left top is one of the many variations used as a mon or crest. The bottom is a detail from a print by Kuniyoshi showing the wheel as part of a robe's fabric design. |

|

|

A thru Ankō |

|

|

Aoi thru Bl |

Bo thru Da |

De thru Gen |

Ges thru Hic |

Hil thru Hor |

|

Hos thru I |

|

J thru Kakure-gasa |

|

Kakure-mino thru Ken'yakurei |

|

Kesa thru Kodansha |

|

Kōgai thru Kuruma |

Kutsuwa thru Mok |

Mom thru Nt |

Ro thru Seigle |

Sekichiku thru Sh |

|

Si thru Tengai |

Tengu thru Tsuzumi |

Yakusha thru Z |

3.jpg)

HOME

HOME