|

JAPANESE PRINTS A MILLION QUESTIONS TWO MILLION MYSTERIES |

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

|

Port Townsend, Washington |

|

A CLICKABLE INDEX/GLOSSARY (Hopefully this will be an ever changing and growing list.)

Kutsuwa thru Mokumezuri |

|

|

The bird on the walnut shell is being used to mark additions made in July 2008. The red on white kiku mon was used in May. |

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

Kutsuwa, Kyōgō, Kyoka, Kyokuba, Kyōsoku, Kyūri, Lake Biwa or Biwako, Richard Lane, Samuel Leiter, Martin Luther, Magaki, Makimono, Maneki neko, Manji, Marumage, Matsu, Matsuri, Matsubame-mono, Matsukawa-bishi, Matsumoto Koshiro V,Meiji Restoration, Mikkyō, Miko, Mikoshi, Mimasu, Mino, Minogame, Mitate, Mitsu buton, Mitsu gashiwa, Mitsu tomoe, Miyagi Gengyo, Mochi, Mokkotsu and Mokumezuri

轡, 校合, 狂歌, 曲馬, 脇息, 胡瓜, 琵琶湖, 人間国宝, 籬, 巻物, 招き猫, 万字, 丸髷, 祭り, etc. |

|

|

TERM/NAME |

KANJI/KANA |

DESCRIPTION/ DEFINITION/ CATEGORY Click on the yellow numbers to go to linked pages. |

|

Kutsuwa |

轡

くつわ |

A bit motif: "These small pieces on each side of the horse's bit not only gave a martial impression when used as crest motifs, but also were later adopted by several Christian families because of the 'hidden cross' design."

Quoted from: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, published by Weatherhill, 1991 edition, p. 106. |

|

Kyōgō |

校合 きょうごう |

Black ink keyblock print used for making color blocks.

David Bull (デイビッド.ブル) of the Baren Forum adds that after the proof prints were pulled they were sent to the designer, i.e, artist, who would indicate what colors were to be used where. 1 |

|

Kyoka |

狂歌 きょうか |

Literally "mad verse" - a 31 syllable comic poem |

|

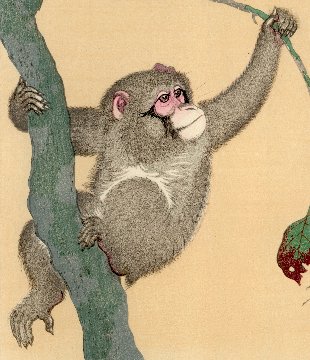

Kyokuba |

曲馬

きょくば |

Circus/equestrian feats: "Japan has had its own circus for nearly 500 years. It is called kyokuba or trick horse-riding was at first its main attraction. Kyokuba started in the middle of the Muromachi period (1394-1573), and from its very beginning consisted of fancy horse-riding, acrobatic acts, comic plays and performances by monkeys and dogs."

Quote from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, p. 483.

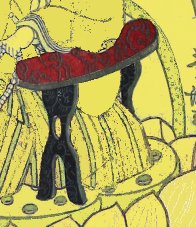

The image to the left is a detail from a Yoshiharu print from 1871 showing a troupe (kyokuban - 曲馬団 or きょくばだん) of female, European riders. Click on the number to the right to see the full print.

A stunt rider is a kyokubashi (曲馬師 or きょくばし). 1 |

|

Kyōsoku |

脇息

きょうそく |

Armrest: "A support board (hyōban) measuring approximately 18 by 6 inches...was elevated on legs at either end, and covered with a cotton-padded cushion. Armrests might be made of imported karaki woods, zelkova, or paulownia, or lacquered and decorated in mother-of-pearl inlay or maki-e."

Quoted from: Traditional Japanese Furniture, by Kozuko Koizumi, published by Kodansha, 1986, p. 102. 1 |

|

Kyūri |

胡瓜

きゅうり |

Cucumber: A kappa's favorite food.

Now...I have a confession to make. The cucumber to the left is not a Japanese cucumber - as far as I know. I bought it in a local grocery store today. I even searched for the one which I thought a kappa might find most attractive. Be that as it may, considering all of the international trade going on this cucumber may well come from Ecuador or Chile or some such place, but definitely not Cuba or North Korea. Of that I can be fairly sure. Besides, all I cared about was finding a decent looking kyūri for your visual and intellectual delectation. Now there's food for thought.

Kiuri is an alternate spelling for kyūri listed in the text volume of the Utamaro catalogue from the great British Museum show. I mention this because a scholarly friend of mine who is fluent in Japanese questioned my original use of kiuri. I revised my entry to this, i.e., kyūri, Anglicized variation.

The Passionate Art of Kitagawa Utamaro, published by the British Museum Press, London, 1995, text volume, entry #119, p. 125. |

|

Lake Biwa or Biwako |

琵琶湖 びわこ |

Japan's largest freshwater lake. 8 of its famous views have inspired many artists. 1 |

|

Lane, Richard |

|

Major author of works on Japanese prints including Hokusai: Life and Work 1 |

|

Leiter, Samuel |

|

|

|

Living National Treasure(s) |

人間国宝

にんげんこくほう

|

Starting in the late 19th century during the Meiji Period the Japanese began to recognize the importance of preserving and protecting tangible national treasures. In 1929 the Preservation of National Treasures Law (Kokuhō Hozon Hō) was enacted. "In the immediate post-World War II years a new effort to nurture traditional crafts and performing arts on a national basis resulted in the promulgation of hte 1950 Law for the Protection of Cultural Assets (Bunzaki Hogo Hō), amended and expanded in 1954 and 1970. The 1950 law covered certain intangible assets (mukei bunka-zai) as well as intangible objects." Artist/craftsmen became known as 'bearers of important intangible cultural assets' or jūyō mukei bunkazai hojisha [重要無形文化財保持者]. This included everything from ceramicists, wordsmiths, fabric artists, lacquerers, doll makers, woodworkers, and performers and practitioners of music and theatrical arts, etc. |

|

"The first list of 31 persons designated by the government for 28 categories of skills was made known on 15 February 1955 and the public immediately transferred the word kokuhō, meaning national treasure, from the 1929 law referring to the preservation of important objects, to the individuals named in the first list, calling them Ningen Kokuhō (Human National Treasures). The termn has been used ever since, despite protestations on the part of the Ministry of Education and he designees themselves that the program is designed not to honor individuals, but to ensure that certain traditional skills will be transmitted for future generations."

65 different skills have been recognized. Each spring the list is reviewed. If an honoree dies he or she is not necessarily replaced with another. Sometimes it is a whole group like a dance troupe which is recognized. A small annual stipend is given to each individual or group. "There is no specific teaching requirement, but the honored individual is expected to find and train apprentices and successors..." Recipients are expected to leave full records, including films, or their practices and to participate in annual exhibitions.

Source and quotes: "Living National Treasures" by Barbara C. Adachi in vol. 5 of the Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan (pp. 60-1).

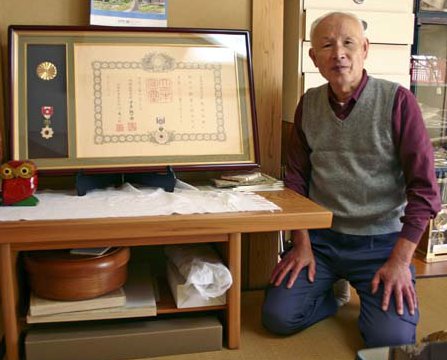

The top image shown above is a photo of Iwano Ichibei kneeling next to his certificate. He is a master paper maker who provides the finest sheets used for woodblock printing. (See our entry for mimi-tsuke below.) The bottom image of the Washington Monument with blossoming cherry trees is by Kawase Hasui (川濑巴水 or かわせ.はすい. He was named an honoree in 1955, but died in 1956. I don't know of any other ningen kokuhō named for woodblock print artistry since then. Itō Shinsui (伊東深水 or いとう.しんすい) was honored in 1950 when his print oeuvre was recognized as a national treasure, but that was before the 1955 designations although he lived until 1972 and could easily have been included in the list, but wasn't. If anyone out there knows of other print honorees please let me know and bring irrefutable proof. |

||

|

|

||

|

Luther, Martin |

マルティン ルター |

Great leader of the Protestant Reformation 1483 -1546 1 |

|

Magaki |

籬

まがき |

A latticework. In the Yoshiwara or red-light district "There were three classes of bordellos..." The houses with the highest class of prostitutes had a latticework which was the largest, most expansive, running from near the floor all the way to the ceiling. This was referred to as the ōmagaki or sōmagaki, i.e., the large or complete lattice. Medium sized houses had lattices which which only covered 3/4th of the space of the ōmagaki. These were called han-magaki or majiri-magaki (a half or mixed lattice). The lowest class houses which never offered the highest rank of courtesans had a half lattice, i.e., the bottom was latticed and the top half was open. These were called so-han-magaki or 'complete half-lattice'.

Source:

Yoshiwara: The

A magaki can also be a fence or hedge as can seen in the image below. 1

|

|

Makimono |

巻物

まきもの

|

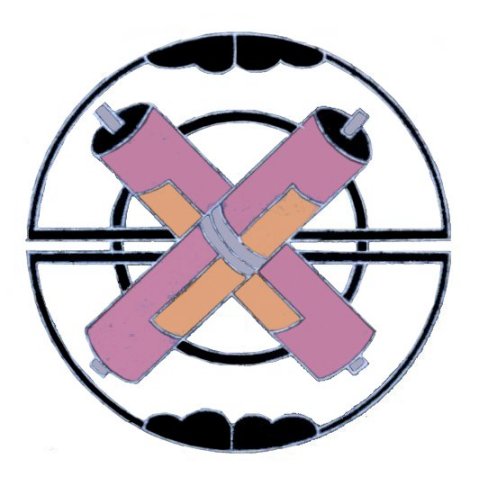

Scrolls: When shown in pairs they are one of the symbolic lucky treasures. They are often displayed crossed.

The image to the left on top is similar to one shown in John Dower's book on Japanese crests or mon. However, Dower lists it under a section on amulets and notes that it was used by a branch of the Ikeda family from Bizen province who remained 'hidden Christians' after the outlawing of Christianity. This design was chosen not because of its well known connection with Buddhism, but because it contained a hidden cross motif. The image shown below that is shown in its more traditional form as one of the lucky treasures. (See the first graphic entry on manji below.)

Source: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, published by Weatherhill, 1991 edition, p. 102. |

|

Maneki neko |

招き猫

まねき.ねこ |

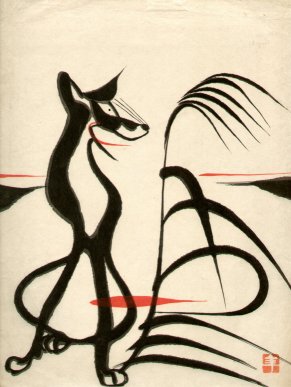

Beckoning cat: When the wearing of earrings became more popular among young men a number of years ago I was incredibly naive. I still am, but now I know that there was a coding system at that time as to which ear it is worn in. Quickly I was taught the anti-gay mantra of "Right is wrong and left is right". And no I am not anti-gay, buy that is the saying. I mention this because there seems to be a lot of discussion out there as to the significance of which paw the beckoning cat has raised. Mock Joya says that there is "...a popular tradition that when a cat passses [sic] its left paw over its left ear it is a sign that visitors will come." It must be true because these creatures are ubiquitous. They come in ceramic, wood, bronze and other forms. They show up in shops and restaurants everywhere. Sometimes the businesses are owned by Japanese, but one is just as likely to run into them in Chinese, Korean or even Waspish establishments.

One story about its origin: There was a famous Yoshiwara courtesan who had a pet cat. As the woman was entertaining a client the cat kept pawing at her and would not go away. Irritated the client drew his sword and beheaded the cat. Its head flew up toward the rafters and it killed a snake which was about to strike the courtesan.

Grief stricken the courtesan gave it an elaborate burial and erected a tombstone. Then she asked a sculptor to recreate the cat in all its features. When done it showed the cat with a left paw raised to its ear. She caressed and fed it - or tried to - everyday. And this was the first maneki neko.

Source and quote: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, p. 110.

The image to the left was created by David Wilcox especially for this site. Thanks David! |

|

Manji |

万字

まんじ

|

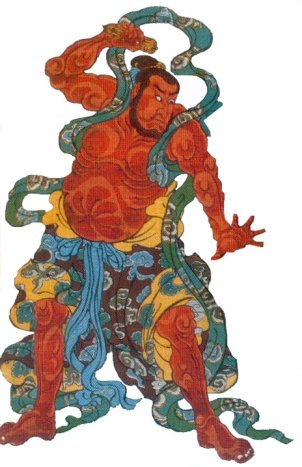

The swastika which has its origins in Indo-Aryan design and was adopted as a positive Buddhist symbol of happiness and well-being. In China it came to mean 10,000 or longevity, even eternity. "In Zen it symbolizes the 'seal of buddha-mind'..."

Quoted from: The Shambala Dictionary of Buddhism and Zen (p. 214)

See also our entry for sayagata.

A personal note: If I have heard it once I have heard it a thousand times that the arms of the Asian swastika go a different direction from that of the Nazi swastika. As best I can tell this is untrue. The Asian swastika was so often incorporated into decorative schemes that it can be found going both ways in the same design. It would seem that people insist that there is a distinct and noticeable difference between the swastika as it was used by the Asians and by that of the Germans because they are trying to exonerate the original source. However, this is really no more realistic than your run of the mill urban myth.

The word 'swastika' is of Sanskrit origin and was meant to convey a concept of well-being, fortune or luck. Among certain Tibetan groups this symbol was always shown rotating counterclockwise... "unlike the Hindu, Jain and Buddhist swastika, whose sacred motion is clockwise."

Source and quote: The Encyclopedia of Tibetan Symbols and Motifs, by Robert Beer, published by Shambala, 1999, p. 344.

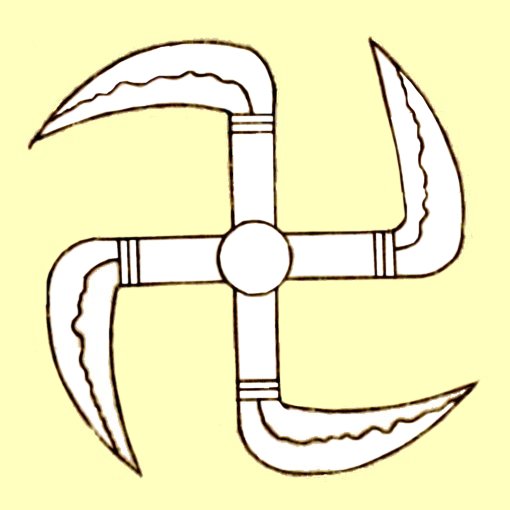

The image to the left is a detail from a Kuniyoshi print.

To the left above the sickle, kama (鎌 or かま), crest or mon functions on various levels. As a sickle it is associated with a protective deity which cuts down its enemies. Combined into a swastika form would simply magnify its efficacy.

Anyone who has studied ukiyo-e long enough will know that the manji is used frequently, almost ubiquitously, over a period of decades. Ordinarily it appears in the most subtle forms on the under-robes - generally in blue and white patterns which are interlaced - being worn by some of the figures. Because of its positive connotations it is rarely seen on the clothing of villains as it is here.

Below is an example by Kunitsuna where the blue and white swastika design is clearly shown. To the left we have isolated a part of the design for easier viewing.

|

|

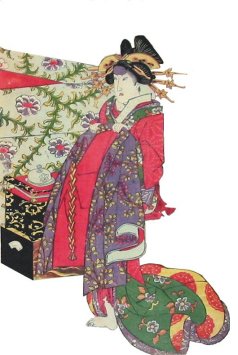

Marumage |

丸髷

まるまげ |

"...lit. a round chignon. the [sic] marumage hairstyle, a traditional coiffure developed during the Edo period (1603-1868). The style is made up of an elevated oval-shaped chignon, a small front tuft, and puffed-out back and side locks. It was widely worn by married women until the end of the Meiji era (1868-1912).

Quote from: Dictionary of Japanese Culture by Setsuko Kojima and Gene A. Crane, p. 203. |

|

祭り まつり |

Festivals |

|

|

Scott Schnell in the Rousing Drum: Ritual Practice in a Japanese Community (University of Hawaii Press, 1999, p. 290) tells us exactly what the purpose of a matsuri is. "The matsuri has been used at various times by its participants to commune with the supernatural, establish or strengthen interpersonal relations, generate and preserve a sense of collective identity, garner prestige, further political ambitions, assert or reaffirm the authority of the local elite and/or the state, challenge that authority, seek retribution for perceived injustices, relieve tensions through cathartic expenditure of energy, settle old scores, and stimulate economic development."

Gloria Ganz Gonick in her Matsuri! Japanese Festival Arts (published by the Fowler Museum, UCLA, 2002, p. 24) adds to what Schnell says: "The essence of matsuri is a prescribed sequence of religious rites held for a group and led by a Shinto priest. The original impetus for establishing a matsuri was usually a felt need to commemorate a historic event of local significance or to seek a fortuitous change in the economic or agricultural outlook of a community. To accomplish this, it was deemed necessary to directly interact with the Japanese deities (kami) and beseech their cooperation." ¶ These festivals "...may include a lively costumed pageant, promenading band, adn semiprofessional dance troops, as well as abundant feasting and drinking." All of this originally has a religious basis, but today such gatherings are increasingly secular. ¶ "Matsuri are hosted by a particular Shinto shrine (jinja) of one community and organized by its neighborhood association (chōnai-kai)." For that reason each matsuri has it own local flavor.

See also our entry on yamaboko or festival float on our Yakusha thru Z index/glossary page. |

||

|

|

||

|

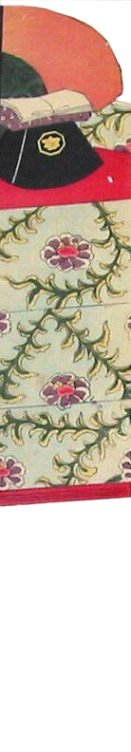

Matsu |

松

まつ

|

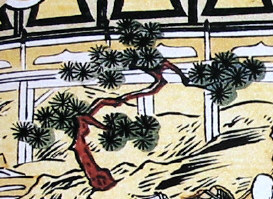

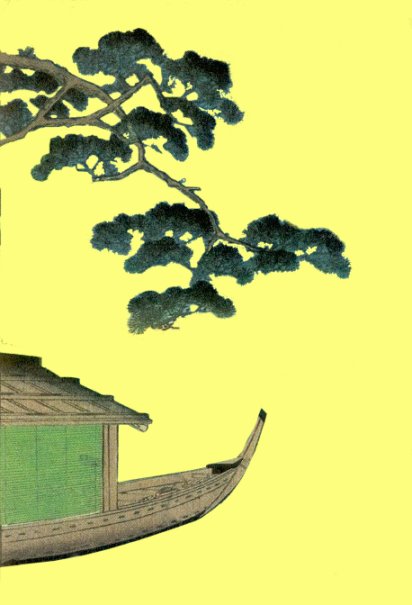

Pine tree - a symbol of longevity, winter and New Years and being virtuous.

The image to the left on top is a detail from a Toyokuni I print showing a painted backdrop.

Being green throughout the year, resistant to strong winds and heavy snows the pine came to symbolize longevity. Several families adopted a variation on the pine motif for use as their family crest. |

|

Matsubame-mono |

松羽目物 まつばめもの |

Kabuki plays adapted from Noh theater 1 |

|

Matsukawa-bishi |

松皮菱

まつかわびし |

Pine bark lozenge motif |

|

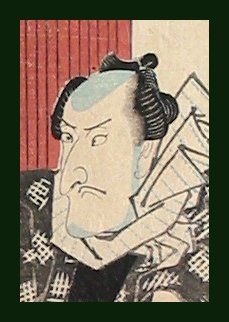

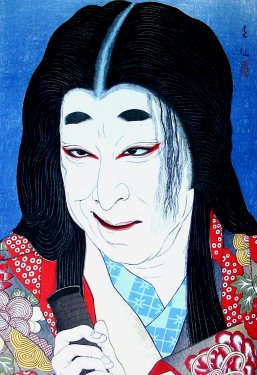

Matsumoto Kōshirō V |

(五世)松本幸四郎

(ごせ)まつもと.こうしろう |

|

|

Meiji Restoration |

明治維新 めいじいしん |

Restoration of Imperial power in 1868 1 |

|

Mikkyō |

密教 みっきょう |

Esoteric Buddhism of the Shingon and Tendai sects |

|

Miko |

御子 みこ |

The female shamans - maidens - of Shinto shrines. They are also known as fujo (巫女 or ふじょ) or even fuyo. |

|

Mikoshi |

神輿 みこし |

A portable shrine |

|

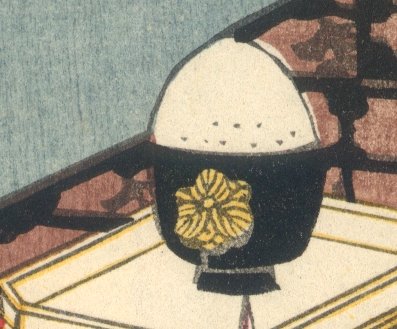

Mimasu |

三升

みます |

Masu means measure and in this case in particular it referred to measurements of rice. A triple masu crest was adopted by Ichikawa Danjūrō I (1660-1704) supposed after a fan gave him an object with this design. After that it was worn by his namesakes. There may also be another connection in that Ichikawa Danjūrō I wrote more than fifty plays for himself to star in, but he did this under the pen name Mimasuya Hyōgo (三升屋兵庫 or みますや.ひょうご). |

|

Mimi-tsuki |

耳付

みみつき |

The deckle edge of a sheet of handmade Japanese paper.

The process of paper making is incredibly labor intensive. Gathering, treating and beating fibers hardly gets at sense of it. Numerous books have been written on the subject. But here we concerned mainly with the end product, i.e., the sheet of paper.

A keta [ 桁 or けた] or wooden frame called a deckle is essential in forming sheets of paper. Liquid loaded with fibers in suspension is ladled from a vat and poured into the keta "...which is lined with a fine slatted bamboo gauze (su) held together with silk thread. The water drips through the gauze and leaves a thin sheet of paper resting on the top." The deckle is shaken to form even sheets. Repeating the ladling process creates thicker paper. The outside edges of each sheet are thinner and clearly show the deposited fibers. This outer edge is the mimi-tsuki. [Source and quote from: Japanese Woodblock Printing by Rebecca Salter, p. 40-41.] |

|

Traditionally deckle edges were trimmed. However, in the 20th century, especially in the shin hanga movement, these edges have often been left uncut and have been considered a desirable quality. These distinctive sheets are often found on the prints of Hiroshi Yoshida, Kotondo, Shinsui, Natori Shunsen, Jacoulet, et. al.

Both Hiroshi and Tōshi Yoshida have written about this deckle edge.

In his 1939 book Japanese Wood-block Printing Hiroshi Yoshida wrote: "Mimi-tsuke (paper with uncut edges) is generally characterized as good paper; the natural edges are preserved for beauty. Cheaper ones have their edges trimmed." (p. 69.)

In 1966 Tōshi Yoshida and Rei Yuki wrote in their Japanese Print-Making: A Handbook of Traditional and Modern Techniques: "Good handmade paper is slightly dark in tone, and its edges are invariably left untrimmed. Paper in this state is known as mimi-tsuki (with ears). The quality of the paper can thus be tested by drawing out the fibers in long tough threads. If the paper is of good quality, these fibers can hardly be torn." (p. 52)

The example to the left was sent to me by my great friend and supporter Mike Lyon. He told me that this sheet was made by Iwano Ichibei (岩野市兵衛 or いわの.いちべえ), a Living National Treasure. |

||

|

|

||

|

Mino |

蓑

みの |

A straw raincoat |

|

Minogame |

蓑亀

みのがめ |

Long-tailed turtle - a symbol of longevity. Actually the tail is algae growing on the backs of some older turtles. 1 |

|

Mitate |

見立て みたて |

Properly the translation of this term is 'selection or choice', but sometimes loosely as 'parody.' |

|

In an article in "Impressions: The Journal of the Ukiyo-e Society of America, Inc." Number 19, 1997, Timothy Clark points out that this term has often been overused and misunderstood. In fact, sometimes it is "an inventive pairing of disparate things, what I described earlier as 'a brain-teasing collision.'"

"A very common pictorial device in Ukiyo-e prints and paintings - reflecting a common pattern of thought in Edo society as a whole - was that of mitate-e, variously translated, but not completely summed up, by such English words as 'parody', 'travesty', 'burlesque', 'analogue'. The basic form of such 'parody pictures' was already apparent in certain genre paintings before Ukiyo-e had ever appeared, and consisted of an ancient tale or incident, acted out or otherwise alluded to in some way by characters wearing contemporary dress."

"The range of subjects suitable for reworking in this way was expanded and codified in a series of printed books and albums by Okumura Masanobu [奥村正信 or おくむらまさのぶ: 1686-1724] during the early decades of the seventeenth century and was often drawn from Chinese and Japanese classical literature or lore, generally reworked in Japanese No plays, popular ballad singing, or Kabuki during the intervening centuries. The tone adopted varied from outright burlesque...to...simple parallels..."

The use of the mitate was often necessitated by effort to avoid government restrictions. "...to avoid censorship by the military government of reporting of contemporary events, many plots are relocated in the distant Kamakura period and the characters given new, but similar-sounding names. Popular literature of the eighteenth century, too, made extensive use of such techniques..."

Source and quotes: Ukiyo-e Paintings in the British Museum, by Timothy Clark, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1992, p. 21. |

||

|

|

||

|

Mitsu buton |

三蒲団

みつぶとん

|

Bedding was obviously very important to courtesan. Not only for comfort for her and her clients, but also as a symbol of prestige. Only the highest order of prostitutes were allowed to own three layers of futons - hence the mitsu buton.

Cecilia Segawa Seigle states: "The tsumiyagu, or 'display of bedding,' was another event that enhanced an oiran's prestige, though it was not as important as sponsoring a new oiran. For courtesans, bedding was a necessary professional accoutrement, of course, and receiving a set of luxurious bedding in splendid fabric as a patron's gift was an occasion for special display. The quilts (futon) and coverlets that a high-ranking courtesan used were all of silk or silk brocade thickly stuffed with light cotton. The taya and oiran used three layers of these quilts for their beds."

Quote from: Yoshiwara: The Glittering World of the Japanese Courtesan, by Cecilia Segawa Seigle, published by the University of Hawaii, 1993, p. 187.

Tsumiyagu may be 積夜具 or つみやぐ.

The image to the left is a detail from two prints of a triptych by Kunisada showing an actor as a courtesan in her bed chamber holding the coat of her lover. Behind her one can see the beautifully covered stacked futons. The detail on the bottom shows more clearly the three separate tiers. |

|

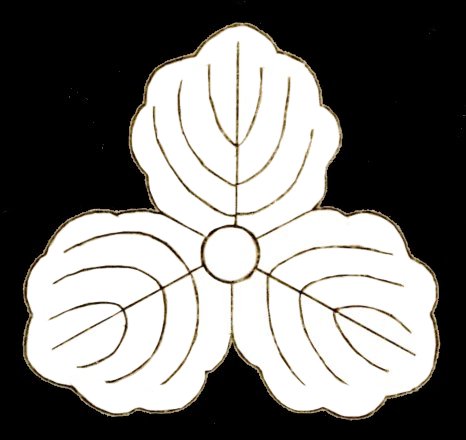

Mitsu gashiwa |

三柏

みつがしわ |

A crest or mon of three oak leaves. (See our entry for kashiwa.) |

|

Mitsu tomoe |

三つ巴

みつどもえ |

A circle formed of three comma shapes. These may represent heaven, earth and mankind. |

|

Miyagi Gengyo |

宮城玄魚 みやぎ.げんぎょ |

|

|

Mochi |

餅

もち |

A sticky rice cake. It is eaten at New Year's, but not exclusively then, because it is said to bring good luck and prosperity. 1 |

|

Mokkotsu |

没骨

もっこつ

|

Timothy Clark describes a series of three Utamaro full-figure portrait prints "...that avoid black outlines whenever possible and replace these with coloured outlines, or 'boneless' (mokkotsu) areas of colour with no outline at all."

The Passionate Art of Kitagawa Utamaro, published by the British Museum Press, London, 1995, Text volume, p. 185.

Those three prints are among the greatest examples of their type. However, if you look closely you will find that elements of prints by many other artists show this 'boneless' technique as part of the overall design. To the left are two details from a Toyokuni I print showing both lined and lineless areas. To see the full print click on the number to the right. 1 |

|

Mokumezuri |

木目摺

もくめずり |

Printing which clearly shows the woodgrain.

Quoted from: Japanese Woodblock Printing, by Rebecca Salter, University of Hawaii, 2001, p. 109.

Quoted from: Japanese Print Making: A Handbook of Traditional & Modern Techniques, by Tōshi Yoshida and Rei Yuki, Charles E. Tuttle Co., 1966, p. 79.

The detail to the left is from a Kunichika print. To see the full image click on the yellow number 1 in the column to the right. 1 |

|

Yoshida also discusses the

opposite effect: Getting rid of the grain altogether. "The best way to

obliterate the impression of the grain of the wood is to grind the surface

of the wood with nagura [

Above and below are photos of horsetails, i.e, pewterwort, i.e., Equisetum hyemale, which is mentioned above by Hiroshi Yoshida as a plant used to scour out wood grains - if that is the effect you want. I hadn't thought of it until I went searching for images of this plant, but horsetail plants were used in the past to scrub pots and pans in the West. Both of these images are shown courtesy of Shu Suehiro at http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm.

|

||

|

|

A thru Ankō |

|

|

Aoi thru Bl |

Bo thru Da |

De thru Gen |

Ges thru Hic |

Hil thru Hor |

|

Hos thru I |

|

J thru Kakure-gasa |

|

Kakure-mino thru Ken'yakurei |

|

Kesa thru Kodansha |

|

Kōgai thru Kuruma |

Mom thru N |

3.jpg) O thru Ri |

Ro thru Seigle |

Sekichiku thru Sh |

|

Si thru Tengai |

Tengu thru Tsuzumi |

|

Yakusha thru Z |

HOME

HOME