JAPANESE PRINTS

A MILLION QUESTIONS

TWO MILLION MYSTERIES

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

|

Port Townsend, Washington |

|

A CLICKABLE INDEX/GLOSSARY (Hopefully this will be an ever changing and growing list.)

Hil thru Hor |

|

|

The bird on the walnut is being used to mark additions made in July 2008. The gold koban coin on a blue ground was used in June. The red on white kiku mon in May 2008. |

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

Jack Hillier, Hinagatabon, Hi no maru, Hiroshige, Hitodama, Hitotsu-me-kozō, Hitsu, Ho, George Hoffmann, Hōgu, Hōju, Hōkaburi, Hōki, Hokuei, Hōmongi, Hōmyō, Hondawara, Hōnoki, Ho-o, Horagai, Hori,Hori Chō, Hori Ken, Horimono, Hōrin, Hori Ōta Tashichi, Hori Take, Hori Uta, Horo,, Horogaya

雛形本, 日乃丸, 安藤広重, 蛭子, 人魂, 一つ目小僧, 筆, 帆, 法具, 宝珠, 帚, 北英, 訪問着, 法名, 馬尾藻, 朴の木, 鳳凰, 法螺貝, 彫, 彫長, 彫兼, 彫物, 宝輪, 彫太田多七, 彫竹, 母衣, 母衣蚊帳 etc.

|

|

|

TERM/NAME |

KANJI/KANA |

DESCRIPTION/ DEFINITION/ CATEGORY Click on the yellow numbers to go to linked pages. |

|

Hillier, Jack |

ジャック.ヒリアー |

Author of Art of the Japanese Book. |

|

Born in Fulham, England in 1912 the son of a postman who delivered mail to Sir Edward Burne-Jones (エドワード・バーン=ジョーンズ) , Rudyard Kipling's (ラドヤード・キップリング) uncle by marriage. Hillier died in Surrey in 1995. From a poor, but happy family he toyed with the idea of becoming an artist - even learning wood engraving - but decided on a more practical route and took a job with an insurance company. He stayed with them until he was 55. During WWII he applied to the RAF to become a pilot, but was rejected for that position because of his somewhat impaired eyesight. However, he did work as an aircrew instructor and in the signal corps.

In an obituary in The Independent he was referred to as the "... leading authority in Europe on the Japanese woodblock print" and other areas. His interests in the field began in 1947 when he bought a portfolio of Japanese prints - some facsimiles. At that time Japanese studies were probably at their ebb. Hillier realized that he would have to learn Japanese so he studied the Harvard-Yenching Course during his train commutes to and from the office.

In time he was invited by Sotheby's (サザビーズ)to be one of their experts. For more than 25 years while working there he assisted in the development of numerous prominent collections: that of Chester Beatty (チェスター・ビーティー), now bequeathed to the Irish state; the Gale collection in Minneapolis; Ralph Harari's collection; et. al. Hillier's first book on the subject, Japanese Masters of the Colour Print, was published in 1954 followed by many other including works on Harunobu, Hokusai, Utamaro, drawings, paintings, etc.

He was a great scholar and connoisseur who made an incredible addition to the field. |

||

|

|

||

|

Hinagatabon |

雛形本 ひながたぼん |

Kimono pattern book(s): We have seen dozens of these which were almost exclusively from the Meiji and Taisho periods. Each page was filled with a typical image: autumn leaves floating on swirling waters; birds in flight; chrysanthemums; etc.

Source: "Patronage and the Building Arts inTokugawa Japan" by Lee Butler |

|

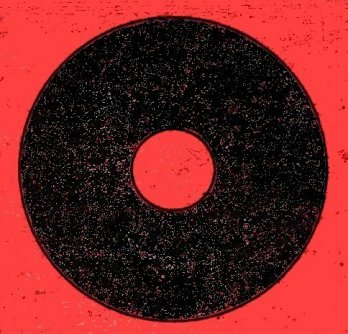

Hi no maru |

日乃丸

ひのまる |

The Japanese national flag: Generally represented as a red disk on a white field often it is seen on a black field on a fan or ogi. "It is popularly known as the Hinomaru (Sun Flag). The design has been a popular one, although it is not known when it was first used." Supposedly when the Mongols were threatening an invasion of Japan the priest Nichiren gave a rising sun flag to the shogun.

Quote and source: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan entry by Yukihisa Suzuki (vol. 5, p. 339) |

|

U. A. Casal in his "Lore of the Japanese Fan" (Monumenta Nipponica, vol. 16, no. 1/2, 1960, p. 81) spoke of a sun design on Kamakura period (1185-1333: 鎌倉時代 or かまくらじだい) fans:

"A favorite décor was a blazing golden sun on a scarlet ground, an ancient warrior symbol.... Their resplendent colours must well have matched the gorgeous armour and brocades of the Kamakura lords.

There were naturally, some variations in these warrior fans too. A red sun may appear on a black or fully gilded ground, or even more conspiciously on a white one, although white could not be lacquered. Such warrior folding-fans are generally referred to as tessen [鉄扇 or てっせん], 'iron fans'. For ordinary use, however, the warrior had similar fans - also with the sun emblem, and sometimes with the moon and stars on the back - of a black lacquered wood or bamboo frame, known as gunsen [軍扇 or ぐんせん] (war-fan). The martial fans always had eight or ten ribs."

In footnote 30 Casal wrote: "Only at the time of the [Meiji] Restoration [in 1868] was the sun-symbol of Victory transformed into a Japanese national flag of a red sun on a white field. In feudal days any colour combination might be chosen, though red was prevalent, either as 'sun' or as 'field'. The Sun with Rays (Naval flag) did not exist before the Restoration..." |

||

|

|

||

|

Hiroshige, Ando |

安藤広重

あんどうひろしげ重 |

Hiroshige (1797-1858)

Definitely one of the greatest artists of the 19th century, but I am not telling you anything am I?

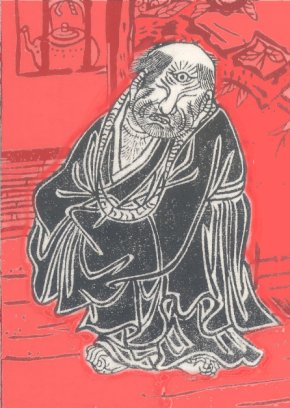

The memorial portrait of Hiroshige to the left is a detail from a print by Toyokuni III. |

|

Hiruko |

蛭子 ひるこ |

The leech child |

|

I am currently reading a novel by an important contemporary Japanese writer. (I will leave him unnamed so I don't spoil the book for those of you who haven't read it yet.) In one exotic scene "Suddenly, unfamiliar greasy objects began to rain down from the sky... There weren't any clouds, but things were definitely falling, gradually more and more fell, until before they knew it they were caught in a downpour." It was raining leeches! What struck me most about this passage was not the bizarre imagery, but the mythico-historic link to the Japanese past.

In the Kojiki, the oldest written chronicle of Japanese literature, the gods Izanagi and Izanami mate, but their first efforts resulted in the leech child "...an amorphous blob, which even at the age three cannot walk.... Realizing that something has gone wrong, abandon the failed offspring in a reed boat onto the ocean and try again." This miscarriage was soon identified with "...failed crops, bad fishing and disorder..." and outcasts. In time hiruko evolved into Ebisu, one of the Seven Propitious Gods. In fact, Ebisu's name is written with the same kanji characters - 蛭子 - although it is pronounced differently. The connection is unmistakable.

An alternate use of kanji characters - 恵比須 - also is pronounced as Ebisu.

Source of the second group of quotes is from Puppets of Nostalgia by Jane Mari Law (Princeton University Press, 1997.) |

||

|

|

||

|

|

人魂

ひとだま

|

Disembodied soul; supernatural fiery ball: Kenkyusha's New Japanese-English Dictionary, 1954, p. 445 translates hitodama as "...a jack-o'-lantern; a will-o'-the-wisp; ignis fatuus; a death fire; a fetch candle; ...a wraith; a doubleganger."

The Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan entry by Inokuchi Shoji (vol. 3, p. 207) describes hitodama as "The spirit that is supposed to depart from the human body at the time of death and afterwards, commonly believed to take the form of a bluish white ball of fire with a tail. Seeing hitodama was traditionally regarded as a premonition of one's own death, although various ways of exorcising them are mentioned in medieval literature. Even today one hears of people who claim to have seen hitodama hovering over rooftops or in graveyards at night. Shooting stars, phosphorescence, and other natural phenomena are sometimes taken for hitodama.

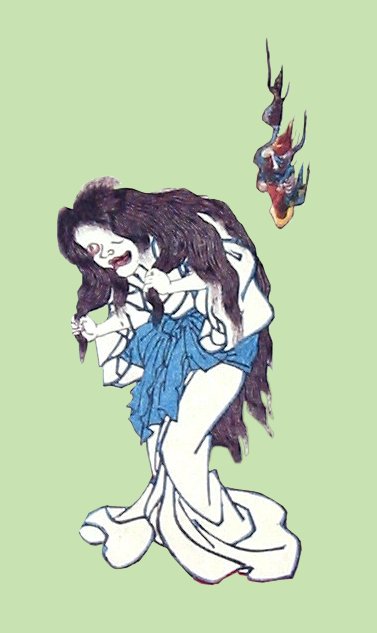

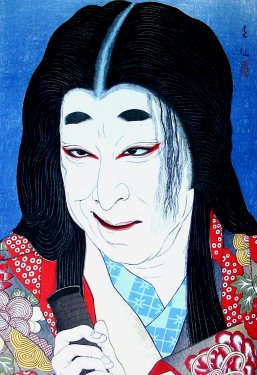

The image shown below is a detail from a print by Kunisada showing the ghost of Oiwa with her associated hitodama.

For another related example of free floating flames see our entry on kitsunebi on our Kesa thru Kuruma index/glossary page.

|

|

Hitotsu-me-kozō |

一つ目小僧

安ひとつめこぞう重 |

One-eyed temple monster or goblin. |

|

Hitsu |

筆

ひつ |

"From the brush of" - a common ending following the artist's signature. The other most common ending is ga (画). 1 |

|

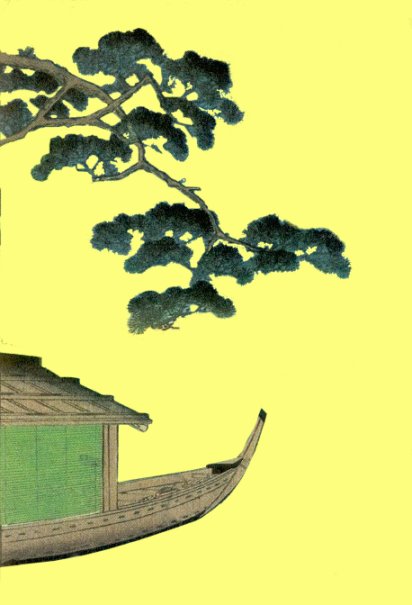

Ho |

帆

ほ

|

Sail crests or mons: "Perhaps the most striking thing about maritime motifs in Japanese design is that they are exceedingly rare." This is what John W. Dower said. But he also added that when there was a net or vessel represented it tended to be something we might notice out of the corner of our eye. Japan was not a maritime state and little emphasis was given this arena. These motifs "...carried comparatively little prestige." Unlike other Japanese terms sailing words seemed to lack the layers of significance and punning found in everything else.

Source and quotes from: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, p. 121.

John Dower: ジョン.ヴ.ダワー. |

|

Hoffmann, George |

ジョージ.ホフマン |

Author of Montaigne's Career 1

Michel Yquem de Montaigne (1533-92): ミシェル・エケム・ド・モンテーニュ |

|

Hōgu |

法具 ほうぐ |

Ritual implements of Buddhism such as the kongōsho (vajra) and the horin (wheel of the law). |

|

Hōju |

宝珠

ほうじゅ |

The jewel motif: Years ago I studied with an expert in Chinese art. He told me that this was the flaming pearl of wisdom that dragons, adult dragons, were forever chasing. (Baby dragons never chased flaming pearls.)

In Japan the term hōju, which can also be pronounced hōshu, translates as jewel.

See also the entry on yakara no tama. |

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Hōkaburi |

ほうかぶリ (?) |

Hand towel tied under the chin like a head kerchief |

|

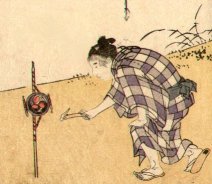

Hōki |

帚

ほうき

|

Broom: In ancient China the broom came to be identified with insight, wisdom "...and the power to brush away all the dusts of worry and trouble."

"The manifold evil spirits are supposed to be afraid of a broom." de Groot in his Religious System of China (vol. 6, p. 972) states "Many families are in the habit of performing a kind of pretence sweeping with a broom on the last day of the year, rather than intending the removal of evil than that of filth."

Source and quotes from: Chinese Symbolism and Art Motifs, by C.A.S. Williams, Castle Books, 1974 edition, pp. 50-51.

Like the Chinese the Japanese saw the broom as an instrument of expelling evil. However, it has another use too: Placing a broom upside down is a sign to a guest that they have overstayed their visit. [My friends have either put on music they thought I would hate or they would change into their jammies.]

In the West it is walking under a ladder or breaking a mirror, but in Japan the simple act of stepping on or over a broom "...is believed to invite a curse or punishment."

"Hoki has also been used as a charm for a safe and easy child delivery in many parts of the country. It is placed upside down at the foot of the mother-to-be in prayer for successful childbirth, as it sweeps away all evil spirits and sickness."

In some locations the broom is offered a bottle of saké until the child is born. Then it - the broom and not the baby - is taken to a shrine and tied to a tree for three days.

Another superstition borrowed from the Chinese was the belief that a broom could keep the dead from moving about on their own.

Source and quotes: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, the Japanese Times, Inc., 1985 edition, pp. 19-20.

The images to the left are from a print by Yoshitoshi representing Jō and his devoted wife Uba. They represent eternal love and are the subject of one of the Noh plays of Zeami Motokiyo (世阿弥元清 or ぜあみもときよ).

|

|

Hokuei |

北英 ほくえい |

Artist fl. 1829-1837 1 |

|

Hōmongi |

訪問着 ほうもんぎ |

There are contradictory sources on the houmongi, but what else is new? Some say that it is a type of kimono worn by married women while others say that being married is not necessarily a requirement. It is either formal or semi-formal and is often worn when making visits or attending weddings. One source says that the brides 'maids' often wear these.

|

|

One distinction does seem to be that this robe generally has an elegant, if understated, continuous flowing design. Very Audrey Hepburnish, but in a Japanese way, of course!

Hōmon 訪問 means 'to visit'. (Like so many specific terms you can find numerous other entries on the Internet if you use alternative, accepted spellings. In this case try 'houmongi'. A suggestion: For those of you who would like to know more or see numerous examples of this type of kimono all you have to do type the entry into Google or cut and paste the kanji or hiragana into the search box. I would suggest doing this even if you don't read Japanese or French or Swahili or Urdu. You will be surprised by what you can pick up simply by looking at more Internet sites. Of course, you have to dig through a lot of c... to find what you want sometimes, but I guarantee it will be worth the effort.

If anyone out there knows anything more specific I would love to hear from you. Also, I would like to find get permission to reproduce an image to illustrate this entry. If you can help there too I would very appreciative. |

||

|

|

||

|

Hōmyō |

法名 ほうみょう |

A posthumous Buddhist name given to the dead. It often appears on memorial or death prints (shini-e) dedicated to actors. It is also referred to as a kaimyō (戒名 or かいみょう).

Source and quote: Encyclopædia of religion and ethics, edited by James Hastings, published by Charles Scribner's Sons, 1917, p. 168

Another form of posthumous name is the okurina (贈り名 or おくりな) which "...have been common with the royalty and among the nobility. In the reign of Kotoku (645-654) the posthumous name Jimmu was given to the first sovereign, and since that time the custom has continued until the present time, when the late emperor is known by the posthumous name Meiji Tenno. These names have for the most part been characteristic of the individual or his reign or some local associated with him."

Ibid. |

|

Source and quotes: Encyclopædia of religion and ethics, edited by James Hastings, published by Charles Scribner's Sons, 1917, p. 168

Another form of posthumous name is the okurina (贈り名 or おくりな) which "...have been common with the royalty and among the nobility. In the reign of Kotoku (645-654) the posthumous name Jimmu was given to the first sovereign, and since that time the custom has continued until the present time, when the late emperor is known by the posthumous name Meiji Tenno. These names have for the most part been characteristic of the individual or his reign or some local associated with him."

Ibid.

The hōmyō was given

by a Buddhist priest right after a person's death. The name was then

inscribed on a wooden memorial tablet or ihai (位牌 or いはい). "From the

eighth century it became the almost universal custom to set up boshi 墓誌, or

monuments, to mark the position of the grave. These were of all shapes and

sizes, and constructed of stone, copper, or other durable material. They

bore inscriptions setting forth the name and rank of the deceased; and in

some cases words were engraved upon the tablets, eulogistic of the dead. Source and quote: Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan, from "Japanese Funeral Rites", by Arthur Hyde Lay, vol. 19, 1891, p. 525 |

||

|

|

||

|

Hondawara |

馬尾藻 ホンダワラ |

Saragossa or gulfweed. A seaweed which dries to a golden color and was used for ornamental New Year's decorations. |

|

Hōnoki |

朴の木

ほおのき |

One of several woods used to print woodblocks. Referred to as Magnolia obovata (Thun.) in the West. Often used in modern printmaking for small prints. 1 |

|

Hō-ō |

鳳凰

ほうおう |

The Phoenix is "...used as a symbol of happiness or good fortune..." Like so many other motifs this has a Chinese origin. Its image "...adorns the roofs of many court and other buildings, as well as the mikoshi or portable shrines carried in procession in shrine festivals."

Quoted from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese (pp. 416-17)

The image to the left is from an original mon design book which I own. |

|

|

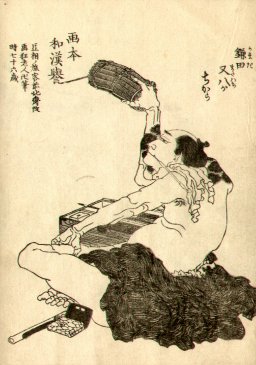

法螺貝

ほらがい |

Conch shell trumpet: Used in India as a military tool prior to the introduction of Buddhism. For that reason it became a symbol of authority. With Buddhism it became "...an icon of spreading the Law.... As such, the conch was counted as one of the eight symbols said to be found on Buddha's footprint." In Japan it was associated with the Senju or 1,000-armed Kannon and was closely linked to the itinerant monks who were known for their esoteric practices. As in ancient India it was adopted as a military signaling device.

Baird also notes that Benkei is often seen in association with the conch shell.

Source and quotes: Symbols of Japan: Thematic Motifs in Art and Design, by Merrily Baird, Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., 2001, p. 128.

"A horn formed by attaching a simple mouthpiece to the end of a conch shell. Of Indian origin, the instrument diffused along with Buddhism throughout Southeast Asia and East Asia, entering Japan via Korea in the Nara period (710-794). It was employed in Buddhist ceremonies and as one of the religious accoutrements other ascetic Shugendō practitioners. The horagai was also used to sound the signal for advance and retreat in premodern warfare."

Quote and source: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan entry by Misumi Haruo (vol. 3, p. 227)

Note that the image to the left is a detail from a print by Yoshitoshi showing Hideyoshi blowing the conch trumpet to let his troops know that it is time to begin the attack at Shizugatake (賤ヶ岳 or しずがたけ). |

|

Quote from: Chinese Symbolism and Art Motifs, by C.A.S. Williams, Castle Books, 1974 edition, p. 83.

"Like Buddha's spiral curls... these shells through ages innumerable, and over many lands, were holy things because of the whorls moving from left to right, some mysterious sympathy with the Sun in his daily course through Heaven." Ibid.

The conch-shell trumpet is often mounted with bronze or silver. They were "...also used as fog-horns by fishing boats..." Ibid. |

||

|

|

||

|

Hori |

彫

ほり |

Carver |

|

"Usually the artist himself did not keep an eye upon all the stages of the printing process and allowed printers and carvers to experiment, which sometimes resulted in new technical achievements. It took about four years to become a skilled printer and at least twice as much before a carver could call himself a specialist. When he reached a high level he put his qualities at the service of the best artists and publishing houses."

Quote from: Ōsaka Kagami, by Jan van Doesburg, published by Huys den Esch, 1985, p. 6.

"Many designers in the history of ukiyo-e were amateur artists, but the engravers were skilled professional craftsmen who underwent a long period of apprenticeship and training before they became masters and were allowed to engrave heads, faces, and major outlines of the figures in prints."

There were so many different carving styles that prints by one artist carved by various engravers often looked like prints by different people. "Some print designers were aware of this issue, although they rarely seem to have had much choice of their engravers." That is why Hokusai wrote one of his publishers requesting that he use a carver named Egawa Tomekichi who he "...could trust to engrave the faces in his pictures the way they were drawn..." and not end up looking like so many other Utagawa heads.

Source and quote: Japanese Woodblock Prints: The Ainsworth Collection, by Roger Keyes, 1984, p. 104.

"...it is certain that some engraving was undertaken by families who worked in their own ateliers and contracted with individual publishers, these engravers often being among the most skilful..."

Less skilled carvers often lived with the publishers and were merely house employees. "Volker has cited one or two instances where the engraver and publisher are the smae person and this may have been more common than is at present believed but the evidence is very scanty." Some carvers were sued for publishing on their own.

Engravers did not just 'copy' slavishly, but often improvised or changed features or elements. The artists did not have direct contact with the carvers and had to convey their wishes through the publishers.

"...it took four years to be an artist, three years apprenticeship to be a printer but ten years to be a first class engraver."

Source and quotes from: The Prints of Japan, by Frank A. Turk, Arco Publications, 1966, pp. 59-60.

"Anecdotes by contemporary blockcarvers about 'the old days' suggest that under the master-apprentice family workshop system, a youngster would start his training to be a nishiki-e blockcarver by cutting lettering. He then moved up to written characters of the prompt books used by the chanters in Kabuki or puppet theaters. From there he learned to remove the excess areas of the color woodblocks... Finally he practiced cutting the outlines for less important parts like the costumes, hands and feet. After more practice only one of the most talented would come to carve facial outlines, until finally he could try the finest carving needed for the elaborate hair-styles of the finishing block." By the end of World War II a carver would have to be 40 to 50 years old before he could tackle the most difficult carving assignments.

Source and quotes: Color Woodblock Printing: The Traditional Method of Ukiyo-e, by Margaret Miller Kanada, Shufunotomo Co., Ltd., 1989, p. 29. |

||

|

|

||

|

Hori Chō |

彫長

ほり.ちょう |

Carver's identifying seal. 1, 2

Active as early as 1861 to as late as 1881.

He carved for Etsu Ka, Hayashi-ya Shōgorō, Sano-ya Tomigorō Wakasa-ya Jingorō, Tsujioka-ya Bunsuke, Izutsu-ya, Enshuya Hikobei, Daikoku-ya Kichinotsuke (?), Daikoku-ya Kinzaburō (?), Tsunoi, Hanabuki-ya Bunzō (?) and 村山源兵衛 (as yet untranslated) and several others who have yet to be identified.

Note: One of the things which has always puzzled me is the role of the master carver in the creation of ukiyo prints. So, I started a search on this particular carver and found a range of dates when his name appeared on the finished prints, a few of the publishing houses he worked for or with and the names of four of the artists he is known to have helped produce. |

|

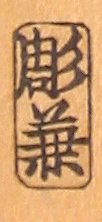

Hori Ken |

彫兼

ほり.けん |

Carver's seal. 1 |

|

Horimono |

彫物

ほりもの

|

A term for tattoo which is also called irezumi.

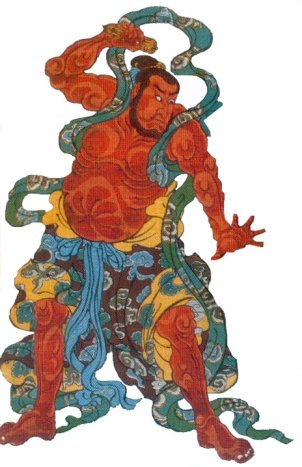

To the left (top) is a detail from a print by Kuniyoshi. It represents Kyūmonryū Shishin from the Suikoden series. Below is a clearer detail of a dragon's head and claws.

BAD BOYS AND THEIR TATTOOS - page 1

BAD BOYS AND THEIR TATTOOS - page 2

|

|

Hōrin |

宝輪 ほうりん |

One of the symbols used by Mikkyō (密教 or みっきょう) or esoteric Buddhism it represents the wheel of the law. The wheel stands for the continuance of existence through birth, death, rebirth, death, rebirth, death ad nauseum. Only the attainment of enlightenment ends the cycle. The kongōsho or vajra is another of the symbols. |

|

Hori Ōta Tashichi |

彫太田多七

ほり.おおた.たしち |

Carver's seal. 1 |

|

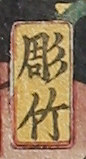

Hori Take |

彫竹

ほり.たけ |

Carver's seal for Yokegawa Takejirō often seen on late Toyokuni III prints. 1, 2 |

|

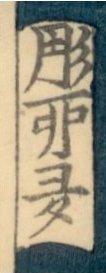

Hori Uta |

|

Carver's seal. 1 |

|

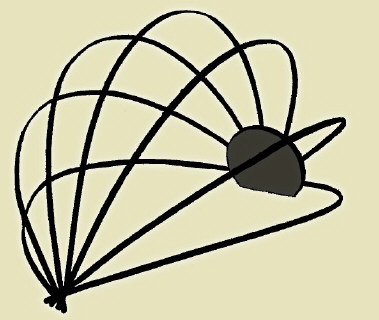

Horo |

母衣

ほろ

|

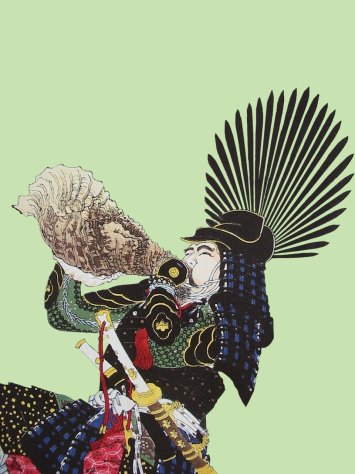

A wicker contraption covered by a thin silk skin worn by warriors and military messengers. Although it gives the impression of movement in ukiyo prints because it looks like a billowing cape it actually is made to function as protection from arrows shot toward a soldier's back.

Note the billowing cloth behind the warrior on the left. This is an isolated detail from a print by Shunshō.

The graphic on the bottom shows the basic shell design of the horo sans threaded netting and silk covering. This image was created for us by David Wilcox (デイビッド.ウイルコックス). Thanks David.

|

|

Horogaya |

母衣蚊帳

ほろがや

|

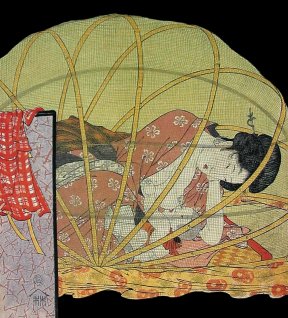

A mosquito net placed over a bamboo frame that was used to protect children. Built along the same lines as the horo seen in the entry shown immediately above this one. There is a wonderful Utamaro print showing a young mother breast feeding her child under such a netting while "...an elder sister peers in from outside the net."

Source and quote: The Passionate Art of Kitagawa Utamaro, published by the British Museum Press, London, 1995, Text volume, p. 155.

The detail of the print to the left by Kunisada was obviously influenced by the virtuosity of the Utamaro precedent. |

|

A thru Ankō |

|

Aoi thru Bl |

Bo thru Da |

De thru Gen |

Ges thru Hic |

Hos thru I |

|

J thru Kakure-gasa |

|

Kakure-mino thru Ken'yakurei |

|

Kesa thru Kodansha |

|

Kōgai thru Kuruma |

|

Kutsuwa thru Mok |

Mom thru N |

3.jpg) O thru Ri |

Ro thru Seigle |

Sekichiku thru Sh |

|

Si thru Tengai |

Tengu thru Tsuzumi |

|

Yakusha thru Z |

安藤広

安藤広

HOME

HOME